As Americans face one of their most consequential elections for years, a subtext is running through the conversations of many of those anxiously waiting for election day: could this country face upheaval or even violence in coming weeks?

The United States was once famous for its peaceful transfer of power. For such a large country, every four years outgoing presidents have stood outside the US Congress as their successor has sworn loyalty to the Constitution.

Sometimes the outgoing president has finished their maximum two terms, and sometimes they’ve been defeated, but it’s been a valued American tradition that the handover of power in what has been indisputably the most powerful nation on earth has happened smoothly and in public.

And then along came Donald Trump.

How is it that a man who has disparaged so many key constituencies — particularly women — still has the support of an estimated 75 million Americans? That’s the reality of the United States as it prepares for Tuesday’s election.

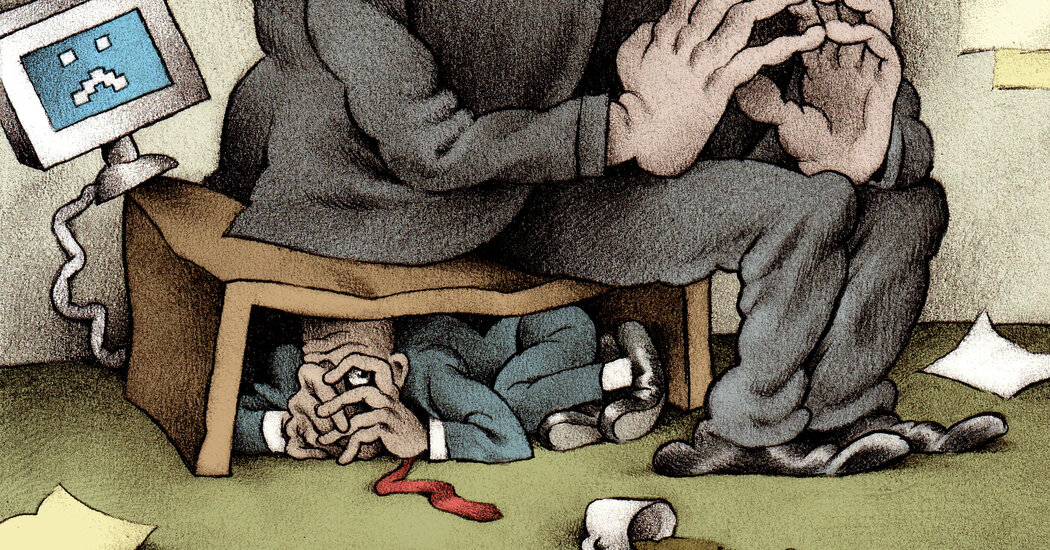

The trauma of the Capitol riots in 2021 remains seared into the memories of Americans. Many Trump supporters stormed the bastion of US democracy in scenes reminiscent of a banana republic.

On top of that, Trump himself has not dispelled that suggestion. In March he warned of a “bloodbath” if he did not win this election, although afterwards his advisers said he was referring to the fate of the US auto industry.

Washington fortified to prevent a 2020 repeat

US authorities are putting in place security measures around the country that have never been seen as necessary before. The New York Times reported that the Department of Homeland Security had advised hundreds of concerned communities on election safety. It reported that at one election centre in Pennsylvania there had been training in “de-escalation tactics”, mobile phones had been updated with panic-button software, bulletproof glass had been installed in the elections bureau office and bullet-resistant film had been fitted on windows.

Washington DC has been heavily fortified, making any storming of the Capitol almost impossible. But authorities are concerned about other government buildings and counting centres around the country.

Some senior diplomats in Washington think the likelihood of violence in coming weeks is low — they say the prosecution of many of the people involved in the Capitol storming on January 6, 2021, will prove a strong deterrent to others, although they don’t preclude the possibility of sporadic outbreaks of unrest.

Much of this anxiety is fuelled by the phenomenon of Trump — an extraordinary political specimen. Trump has reached the point where he can say anything and do almost anything and it will not erode his support from half of the American population.

This week he said if re-elected president he would “protect” women “whether they like it or not”. He also said that Liz Cheney, a former Republican senator and daughter of one of the Republican Party’s elder statesmen Dick Cheney, was a “war hawk” and should understand the experience of having “guns trained on her face”.

Americans were not shocked by this commentary on one of his staunchest critics. In fact, Trump seems to have crossed the threshold of shock.

With two assassination attempts against Donald Trump during the campaign, violence is already a part of this election’s story.

Today, the US is bitterly divided. Lilliana Mason, associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, has studied the polarisation in today’s America. Her research found 40 per cent of registered voters look at the “other” side as “not humans”.

She found 50 per cent of people who identify with one side of politics are willing to say the other side is “evil” while up to 40 per cent of party loyalists are willing to de-humanise people in the other party.

Loading…

The ground is being laid for court challenges

What is making many Americans nervous is that in recent days Trump has begun to build a case that this election has been rigged. He’s alleged that Pennsylvania is “cheating big” on votes in pre-polling.

Pennsylvania could prove to be the most decisive state. Trump’s early claim of electoral malfeasance has been rejected outright by election officials and most of the media but for Trump it works both ways — if he wins, it will be irrelevant, and if he loses he’s already put the idea into the minds of his supporters if he wants a big public reaction.

Trump doesn’t have the power of the state that he had behind him as president in 2020, but deepening of his message about mistrust of institutions shows another potential card in his hand.

In 2020, Trump fought legitimate election results in the courts. But this election is expected to be the most litigated in America’s history, with both parties recruiting lawyers in every state, wargaming scenarios and starting to file lawsuits.

Lawyers, party representatives and volunteers will be on hand across the country to scrutinise ballots.

In some key states, particularly in Georgia, incumbent state Republicans have passed controversial changes to electoral laws since 2020.

He may make successful challenges in some states, or have a low success rate like in 2020, but at the least it could slow down the result, and in doing so cast doubt on its legitimacy.

Why Trump’s rhetoric works with voters

Harris has tried to make Trump’s character a central issue. She’s described him as “unstable, obsessed with revenge, consumed with grievance and out for unchecked power”.

Despite this, Trump is still competitive. One strong theme I’ve picked up talking to many Americans is that while they are sometimes appalled by things Trump says they think a strong economy and jobs are more important than rhetoric.

The view of many working-class Americans is that in an era when a good job is difficult to find, being offended by the rhetoric of any politician is a luxury.

There’s a reason Trump’s political brand endures. He resonates with a vast number of Americans who feel alienated from any economic success. This alienation is not new — but what’s different is that no politician before him has so successfully harvested this anger.

This in itself is a paradox. Trump’s life story could not be further from the lives of the economic underclass. His own life in Manhattan as a property developer, as evidenced by the glittering Trump Tower, is a world away from the working poor who deserted the Democrats and elected him president in 2016 over Hillary Clinton, seen by the working poor as privileged and elitist.

This is where Trump’s choice of vice-presidential running mate becomes crucial. While the left in the US has been appalled by the choice of a hardline conservative, JD Vance is from the very constituency which could deliver this election for Trump.

Vance writes in his book Hillbilly Elegy: “Working class whites are the most pessimistic group in America. More pessimistic than Latino immigrants, many of whom suffer unthinkable poverty. More pessimistic than black Americans, whose material prospects continue to lag behind those of whites. While reality permits some degree of cynicism, the fact that hillbillies like me are more down about the future than many other groups — some of whom are clearly more destitute than we are — suggests that something else is going on.”

Although Vance wrote this well before his vice-presidential candidacy, that “something else” is what’s at the heart of Trump’s support among half the country. “As the manufacturing centre of the industrial Midwest has hollowed out, the white working class has lost both its economic security and the stable home and family life that comes with it,” Vance wrote.

Loading

Trump has nothing to lose

This election is impossible to predict. There are too many wild cards — including Trump himself.

Along with the unpredictability, there’s a distinct sense among many Americans that should Trump lose, there may be violence.

A recent poll found a majority of voters in the so-called swing states were concerned some Trump supporters would resort to violence should he lose the election. The Washington Post-Schar School poll found 57 per cent of the 5,000 registered voters were concerned about violence.

A separate poll, conducted by the Associated Press-NORC Centre for Public Affairs Research, found that four in 10 registered voters said they were “extremely” or “very” concerned about the possibility of violence in the days after this election.

Trump is 78. Many Americans say he has nothing to lose, and that his bitterness from having the 2020 election “stolen” from him — he still insists that it was — if added to any defeat this week could see him either openly urging violence or “dog-whistling” to create unrest.

If Trump loses, he faces years of court cases — including possible criminal charges. Victory would mean he’s able to forestall any such proceedings.

Bruce Wolpe, a non-resident Senior Fellow at the United States Studies Centre and author of Trump’s Australia, sees violence as a real possibility if Trump loses.

“The scale of violence I think is tied to the size of the margin of defeat,” says Wolpe, also a former adviser to the Democrats in Washington. “The closer the election, the greater the temptation to employ violence. We will see.”

Washington DC has been well fortified — any storming of the Capitol would be difficult. The concern this time by the Department of Homeland Security is that violence could be directed at government buildings in other cities.

The fear of violence infuses many of the conversations at the moment. The caretaker in my Washington hotel said he feared there would be “upheaval” whatever the result.

If Trump loses, he said, then his supporters may take to the streets. And if Trump wins, the shake-up could be so radical that many would react against that, which in turn could lead to civil unrest.