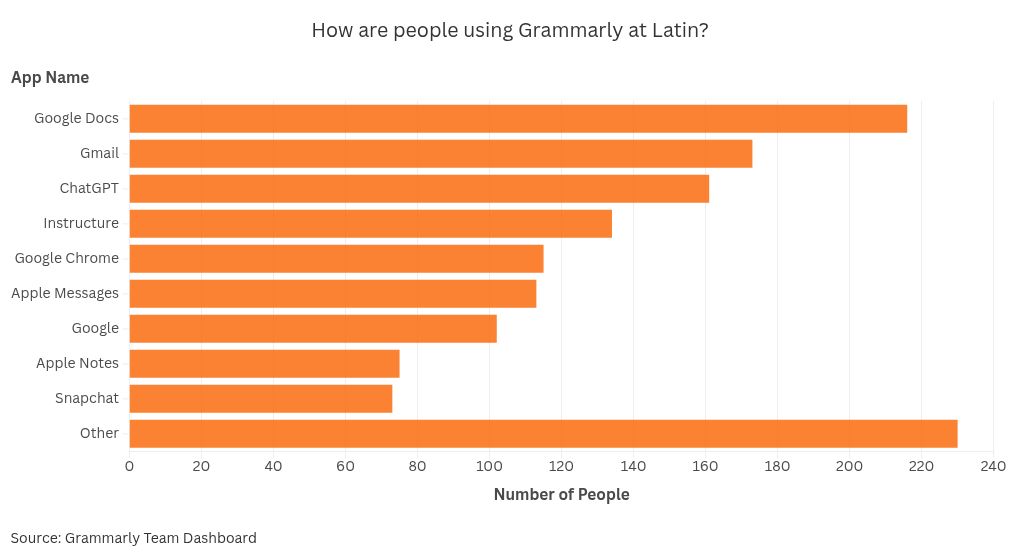

Since Latin announced the purchase of a schoolwide Grammarly subscription on Sept. 17, more than 250 eligible students and faculty have installed the extension, and have thus begun sending every word they type on any app to Grammarly servers.

Grammarly is just one of many platforms that collects student data online. However, many students don’t understand how these digital services access and potentially use their data. For example, if you install Grammarly systemwide, it sees what you type in iMessage, ChatGPT, and Snapchat.

“I didn’t know Grammarly could access that much beyond my docs,” senior Shozib Wasim said. “I was required to install it for class.”

While Grammarly does not share what you type with Latin School, it does collect and share other information, including what sites you use, what tone you typically write in (as analyzed by their AI), and if your writing is AI-generated (if Authorship is enabled).

For non-education customers, stored writing is even used to train AI models.

This data is collected even though it is not strictly necessary for Grammarly to provide grammar suggestions, which only some students realize. Freshman Charlie Winter is one of these students, intentionally installing Grammarly only where Google Docs can see.

“I only installed the extension in my browser,” he said. “If I installed it on my computer, it would see everything.”

On the other hand, Ava Schwartz, a freshman just beginning the cybersecurity unit of 9th-grade Affective Ed, was surprised to hear about Grammarly’s level of data collection.

“I didn’t know any of this was happening,” she said. “I think the school could do better at teaching about this.”

The gap between Charlie and Ava’s awareness reflects a larger pattern of digital illiteracy at Latin. Computer Science Department Chair and teacher of the cybersecurity Affective Ed unit, Bobby Oommen, estimated that “only 10%” of Latin students understand the data they are giving out online.

“I think a lot of people’s level of understanding is, ‘If I’m on an incognito browser, I’m totally free,’” he said. In reality, private browsing does not hide your internet activity.

Beyond individual applications, misconceptions about data collection also surround networks and how data inherently moves across the internet.

“People in general think that they can do whatever they want, delete it, and it’s going to disappear,” Latin’s Director of Technology and Data Security Marc Blettry said. “We know that, unfortunately, it stays there and there is a way to find it at some point.”

Latin’s handbook reflects this reality, explicitly stating that students have “no right to privacy using Latin’s technology and network resources.” But how does this policy actually play out, and how many students actually understand what is technically possible for the school to access?

When your computer tries to communicate with any website, a “request” is sent to a nearby router device. For the router to do its job—getting your request to the right place on the internet—it has to know where the request is meant to go, which means any Wi-Fi you join can see which domains you visit.

Securly, Latin’s internet filtering service, accesses this information and uses it to ensure that students are not shown inappropriate or dangerous content—as is required by federal regulation, including the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule and the Children’s Internet Protection Act. However, to use Latin’s Wi-Fi, students are required to install an additional certificate for Securly, which gives it the ability to see more than just domains visited.

Requests secured with modern security standards function much like physical mail: While a mailman can see the destination address, they cannot see the message without opening it. If they do try to open it, your computer treats it like obviously tampered mail: It knows something is off and will warn you that you are accessing content that is not safe or legitimate.

Installing the Securly certificate tells your computer to ignore the specific kind of “tampering” that happens on Latin’s Wi-Fi. Some opt-in Securly products like Aware and Discern use this data to scan internet activity with AI for misbehavior and potentially dangerous intentions. Latin, however, unlike many K-12 schools, decided not to purchase these products.

“Aware… we decided not to go that route. Aware gives a lot of access to a school, to the students’ activity, to a point that, I believe, is too much,” Mr. Blettry said. “We want to respect our students. [Aware] will pretty much read an email you are sending. I don’t believe that’s right.”

Instead, Latin uses the certificate to unlock different types of content for different grade levels.

“[The certificate is] the only way we are able to recognize your level of access,” Mr. Blettry said. “Without that tool, we would have to block the entire content of the internet.”

This feature is included in Securly Filter, the only Securly product Latin subscribes to besides Securly Home (which lets parents add parental controls to school devices).

“Securly Filter is a gatekeeper for websites,” Assistant Director of Information Technology Chad Nielsen said. “It does NOT track what you do inside a website.”

Students like Shozib know that Latin’s usage of Securly is minimal, but they still reflect on the fact that the certificate gives Latin a high level of technical access, which other institutions might apply different philosophies to.

“I know that getting on Latin Wi-Fi essentially gives [Latin] access to everything I do if they wanted, and I don’t think others realize how much power it gives,” Shozib said. “That said, I trust Latin, and don’t believe they’d use it for anything without proper cause—even if the handbook technically says they can.”

The common thread between Grammarly and Latin’s Wi-Fi isn’t surveillance. It’s that students rarely understand how they can be tracked online, let alone how they are being tracked.

Mr. Oommen’s cybersecurity unit of Affective Ed represents one effort to close that gap, which has students enable the Privacy Report on iOS and reflect on the different ways that they are being tracked.

“One student was surprised that ESPN tracks personal information,” he said. “The question was: for what purpose, and why?”

Ultimately, Director of Academic Affairs and former Computer Science Department Chair Mx. Hansberry emphasized that the school’s goal for data literacy is to help students make informed choices about their usage of the internet—not scare them off the internet.

“[Digital literacy] is about how much information about yourself you are comfortable putting online, or how much information you are comfortable being used to sell you things and train AI models,” Mx. Hansberry said. “[It] is changing really quickly, and the definition sometimes changes faster than everyone can keep up with.”