In 2013, China was the largest maker of electronics, and the country imported the vast majority of chips required for manufacturing smartphones and PCs, as it had no microelectronics production capabilities of its own. Driven by concerns surrounding dependence on foreign technology, China’s State Council launched what it called the ‘Made in China 2025‘ initiative.

The plan aspired to turn China from a global factory into something more lucrative, and included a 70% self-sufficiency in semiconductors by 2025. Over a decade and hundreds of billions in spending later, China has made remarkable progress. Yet, it is still decades away from matching the capabilities of the global semiconductor industry.

Go deeper with TH Premium: Chipmaking

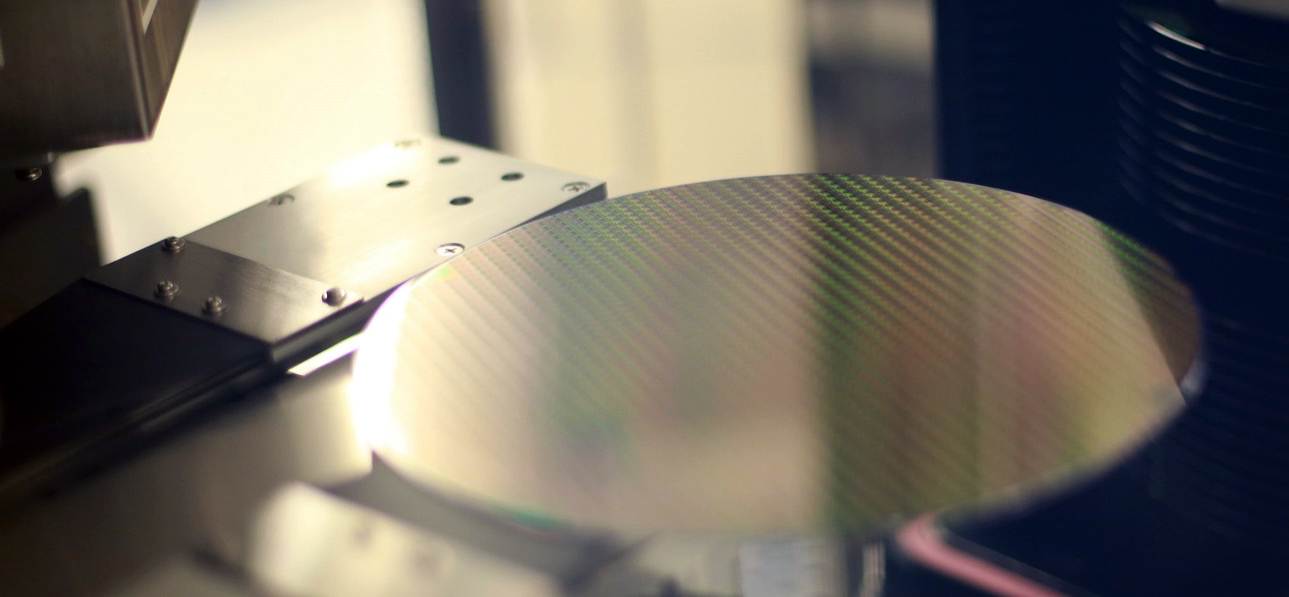

Initially, China tried to fast-track its way into the global memory industry by acquiring Micron for about $23 billion, which made a lot of sense as the majority of chips consumed by the Chinese industry at the time were memory chips. After Micron rejected the takeover attempt by Tsinghua Unigroup (to a large degree, because the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States intervened). Local authorities in Fujian, China, established the Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Company (aka Fujian or JHICC), a DRAM maker, which signed an agreement with UMC to develop a DRAM process technology in May 2016, just months before it began construction of its $5.65-billion 300-mm fab in July 2016.

It later turned out that instead of developing its own DRAM technology independently, UMC recruited engineers from Micron’s Taiwanese subsidiaries and told them to obtain technical specifications as well as detailed knowledge of Micron’s manufacturing processes and related know-how before leaving their employer. A legal battle ensued, and in 2021, UMC reached a global settlement agreement.

In parallel with trying to acquire Micron or acquire its semiconductor production IP using other means, the Chinese government established its China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (also known as the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, and the Big Fund) to directly fund the local semiconductor industry.

The focus of the first phase of the Big Fund (2014 – 2018) was to build basic semiconductor manufacturing capacity and reduce reliance on foreign foundries and memory suppliers; the goal of the second phase (2019 – 2024) was to establish a true semiconductor supply chain that could develop advanced process technologies and build sophisticated semiconductor production equipment (SPE). The goal of the third phase (2025 – 2040) is to make the domestic supply chain fully independent, including building all fab tools and core technology domestically. Somewhere along the line, the Chinese government stretched the Made in China 2025 project to 2030 and then to 2040 when it comes to developing the semiconductor supply chain.

The Chinese government has raised and spent tens of billions of dollars on its Big Fund-backed projects, with The New York Times claiming that it has spent some $150 billion on its semiconductor-related endeavors. While the sum looks formidable, it should be noted that it might be a gross understimation, as government-linked and private companies have also invested tens of billions of dollars in the domestic chip industry.

For example, a recent UBS note to clients indicates that analysts from the company predict that Chinese entities — private, public, and multinational — would have spent about $280 billion on wafer fab equipment (WFE) alone from 2022 to 2028. When combined with other chip-related projects that span from the development of electronic design automation (EDA) tools all the way to the design of actual chips and producing sophisticated raw materials, we are probably looking at tens of billions of dollars more.

If we combine everything that has already been spent on China’s semiconductor industry — by private, public, and multinational entities — since 2013 ~ 2014, we would be looking at a sum that by far exceeds $150 billion. But what has China achieved so far?

Chip development breakthrough

Arguably, the most important and impressive breakthroughs for the Chinese semiconductor industry in recent years are the established chip design operations at multiple highly competitive Chinese companies, including Alibaba, Baidu, ByteDance (according to reports), Huawei, and Tencent. In addition, multiple pure-play chip designers emerged with fairly competitive products, such as Biren Technology, Cambricon, Enflame, MetaX, and Moore Threads, just to name a few.

In 2026, Huawei not only builds competitive system-on-chips (SoCs) for smartphones and PCs as well as 5G modems, but it also offers competitive AI accelerators that can challenge some of Nvidia’s data center GPUs. In addition, the company builds rack-scale AI solutions that can challenge Nvidia’s NVL72 GB200. The same can be said about products by Biren, Cambricon, or Moore Threads, which produce AI processors that can, on paper, be considered competitive enough when compared to Nvidia’s GPUs.

China’s breakthroughs in creating a credible chip design ecosystem were not a result of a single decision, but rather the convergence of policy support, market scale, access to global manufacturing, and a large pool of engineering talent. These hiring efforts include talent poached from Taiwan or the U.S. and from large multinational companies like AMD or Nvidia that employed hundreds of engineers in the People’s Republic.

One of the most important factors was the country’s decision to prioritize fabless semiconductor development in the mid-2010s, which lowered capital intensity while encouraging the establishment of chip design companies. Another decisive factor was access to the global semiconductor ecosystem before export controls tightened: Chinese designers relied on EDA tools and IP blocks developed by American companies and made their chips at TSMC, on the same product lines as AMD, Broadcom, Nvidia, or Qualcomm.

Finally, market structure played a critical role: China’s enormous domestic demand for everything, from application processors for smartphones to data center-grade AI accelerators, created a guaranteed early customer base that reduced commercial risk for new semiconductor startups. Unlike traditional chip designers, which compete globally, many Chinese design firms could compete within the domestic ecosystem and, at times, enjoy support from the government. As a result, China is now among a few countries that can develop a variety of complex and competitive chips for existing and emerging applications.

Dozens of fabs across the country

China’s progress in semiconductor manufacturing and process technology development has been far more incremental than in chip design, but it has still produced several tangible successes over the past decade.

First and foremost, the country has built dozens of fabs across the country that are now producing chips on a variety of production nodes. Foundries such as Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), Hua Hong Semiconductor, and Shanghai Huali Microelectronics Corporation (HLMC) successfully expanded mature-node production at 55nm, 40nm, 28nm, and specialty nodes, including analog, embedded non-volatile memory, mixed signal, power management, and RF processes.

When it comes to memory production, China achieved arguably its most visible semiconductor manufacturing breakthrough. Yangtze Memory Technologies Co. (YMTC) has developed world-class 3D NAND memory with its Xtacking architecture, which separates logic and memory wafer processing and enables higher I/O performance. Similarly, ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT) established domestic DRAM production at mainstream nodes, successfully ramped volume manufacturing, and quickly established positions in local markets.

Still no leading-edge process technologies

Although there are now dozens of semiconductor production facilities that produce chips on mature nodes, only SMIC has managed to develop several generations of 7nm-class fabrication technologies. Hua Hong and HLMC offer 22nm and 28nm-class manufacturing processes, and yet are still unable to crack FinFET-based nodes.

One may argue that the main success of China is to build dozens of fabs where there were zero. Also, it is an indisputable achievement of SMIC to build three generations of 7nm-class nodes without access to EUV or even the most advanced DUV tools while leveraging multipatterning. While this is indeed correct, this also shows boundaries for China’s semiconductor industry.

China’s semiconductor production equipment industry has been developing alongside the chip production industry while taking many notes from international rivals. China-based producers of fab tools have poached engineers from leading SPE producers, reverse-engineered tools, and obtained significant support from the government.

This helped such Chinese wafer fab equipment suppliers like ACM Research (which is technically based in the U.S. and did not get all the benefits from the Chinese government), Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc., China (AMEC), and Naura Technology Group, as these companies now produce world-class tools for cleaning, deposition, etching, and plating.

Lithography and advanced inspection tools remain the clearest exceptions to this progress. Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE), China’s primary lithography vendor, currently produces steppers suitable mainly for mature nodes, such as 90nm, 110nm/130nm, or 280nm. Several years ago, reports suggested the development of a 28nm-capable immersion ArF system; the company has never confirmed mass production. The same applies to reports that SMIC was testing a 28nm-class tool from Shanghai Yuliangsheng Technology Co., as its readiness for production remains unclear.

For now, advanced lithography and advanced inspection equipment represent the most significant technological bottlenecks for China’s semiconductor industry. Without access to ASML’s leading-edge litho and inspection tools, companies like SMIC, Hua Hong, or HLMC cannot develop more advanced nodes or initiate mass production using these technologies. Yet, as Chinese companies cannot build leading-edge equipment, foundries and memory makers are stuck with existing fabrication processes. This will not change any time soon.

Money is not enough

In 2026, China’s semiconductor industry has reached a point where it can no longer develop further, no matter how much money is being poured into it. To build advanced immersion DUV lithography or inspection tools, Chinese companies must iterate their technologies gradually instead of leaping ahead with the help of foreign specialists or by copying ‘best known methods.’

Modern DUV lithography scanners are at the intersection of ultimate mechanical precision, advanced optics, fluid dynamics, and real-time computational control, where even nanometer-scale deviations can render patterns unusable. Mastering this level of system integration requires decades of accumulated expertise across optics, motion control, software, and process tuning, areas where only a handful of suppliers have achieved production maturity.

As a result, despite visible progress in other segments of wafer fabrication equipment, China remains years behind the most advanced DUV capabilities and at least a decade behind when it comes to EUV tools.