The cold realists in Beijing were ‘deeply shocked’ by the American strike on Venezuela and have called on the United States to release President Nicolás Maduro and his wife at once.

It is only two years since the Chinese leader Xi Jinping gave Maduro a red-carpet welcome on a state visit and vowed support for his ‘efforts to safeguard national sovereignty…as well as Venezuela’s just cause of opposing external interference.’

It is only two days since Maduro received Xi’s special envoy in the Miraflores presidential palace for talks on more than 600 agreements that have bound the two countries together on energy, infrastructure, finance and political co-operation. If the visit by Qiu Xiaoqi, a heavy-hitter who has served as Chinese ambassador to Brazil and Mexico, was meant to deter American action, it failed. Superficially, the fall of Maduro looks like a net setback for China on the political, diplomatic and strategic fronts.

It may be more subtle than that. Although China does not react quickly to complex international events, there are four questions which will preoccupy its leaders this week – and not all of them look bad.

The first question, forever paramount but never said, is the military one. There will be intense scrutiny of the tactics and intelligence skills which allowed US forces to suppress Venezuelan air defences, turn off the lights in Caracas and stage a precision capture, livestreamed to a delighted President Donald Trump at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida.

Not much to worry China here: Venezuela’s defences were in such a shambles that Maduro had recently asked Xi for new radar systems, asked his other ally, President Vladimir Putin, for help to repair the engines for Russian Sukhoi-SU20 MK2 warplanes (only five were said to be operational) and sought missiles, drones and GPS scramblers from Iran.

The contrast with China’s own modern arsenal is stark and will spur on the Politburo in its race to beat American warfighting technology. A study of the raid will also help the PLA’s own scenario planning for a ‘decapitation strike’ against the leaders of Taiwan.

A second question for China is its energy deal with Venezuela under which the Maduro regime repaid loans with discounted shipments of oil. Official figures showed China was the destination for 700,000 out of 1.2 million barrels of oil a day shipped by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), Venezuela’s National Oil Company.

There had been hard bargaining because Venezuelan crude is ‘heavy’ and Chinese refineries may have struggled to produce fuel at a competitive price. It was a textbook state-to-state exchange made for political, not economic, reasons. The Chinese will have been soothed by President Trump’s early assurance that the oil will still flow – but he has not said at what price. On balance, this hands leverage to the American president.

The third question is where the Venezuelan strike leaves America’s position and China’s status in the world. Here there is no doubt that Beijing feels exultant. Its spokesperson urged the US to ‘stop toppling the government of Venezuela’ adding that the American action ‘is in clear violation of international law, basic norms in international relations and the purposes and principles of the UN Charter.’

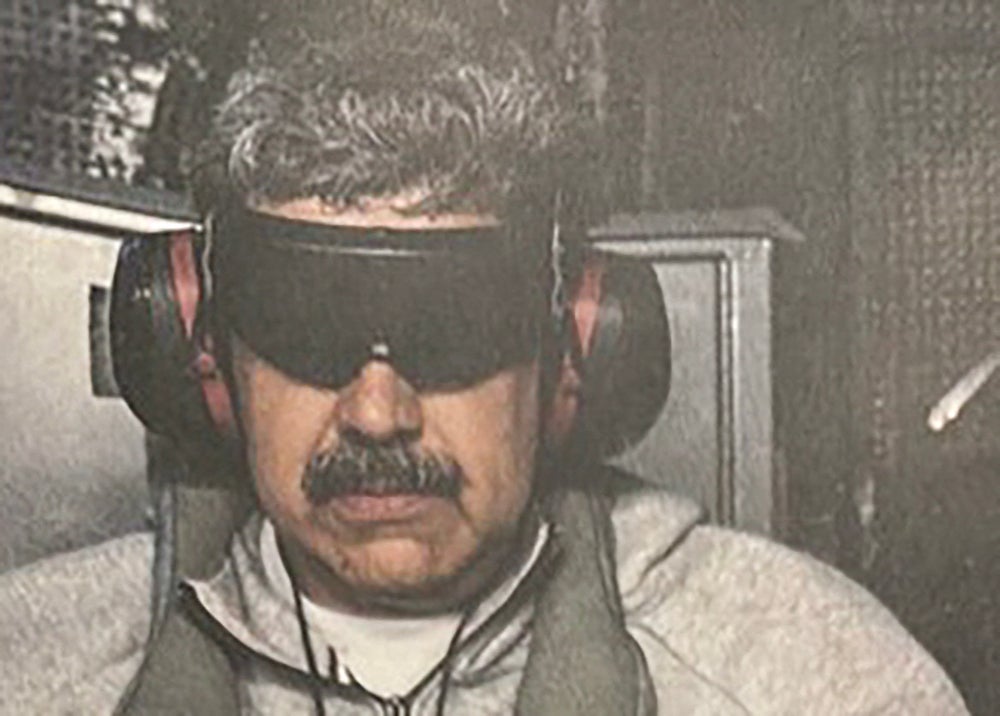

These were the unblushing themes promoted by China since Maduro and Xi attended the Victory Parade in Moscow staged by Putin on 9 May last year to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War Two. Maduro did not, however, make it to Xi’s own parade on 3 September, sending the president of the National Assembly instead as US forces gathered in the Caribbean. But his government endorsed the ‘anti-fascist’ script adopted by China, Russia and North Korea.

Xi talks about restoring the ‘authentic history and values’ of the UN system; successfully rallying disquieted nations of the ‘Global South’ to the cause.

And while Maduro may not grace the podium at the UN General Assembly in New York in person again, his captivity not far away hands a rhetorical weapon to opponents of the United States; not that the Trump administration cares about that.

The fourth question for China is what it means for Xi’s ambition to reunite with Taiwan. The Chinese leader is far too cautious to link the two openly. But a clue can be found by decoding his foreign ministry’s statement, which said ‘China strongly condemns the US’s blatant use of force against a sovereign state and action against its president.’

Of course, China does not regard Taiwan as a sovereign state but a renegade province, while it does not recognise President Lai Ching-te as a legitimate head of government but a ‘doomed traitor.’ Therefore the Venezuelan precedent does not apply.

Legally, from Xi Jinping’s point of view, any action to reclaim Taiwan will be merely an internal matter of no concern to foreigners. A strike to take it back could be made to fit a world order in which America dominates the western hemisphere and China dominates the east. Politically, President Trump has just made it easier.

Michael Sheridan is author of ‘The Red Emperor: Xi Jinping and His New China’ (Hachette Books) and ‘The Gate to China’, an acclaimed history of Hong Kong