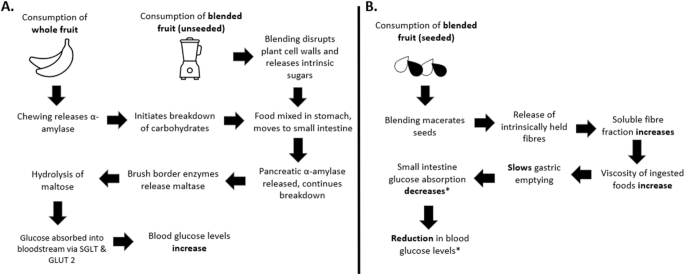

In recent years, there has been a rise in popularity and subsequent consumption of both commercial and home-prepared smoothies due to the perceived health benefits of increasing fruit and vegetable intake in this way [1]. Under current public health guidance in the UK and Europe, smoothies are considered as fruit juices and should be limited to <150 ml/day and can only count towards one portion of fruit and vegetables. The current advice is largely based on the perceived ability of juiced fruits to increase the bioaccessibility of free sugars in the gut, resulting in faster uptake into the blood compared to whole foods and causing an elevated post prandial glycaemic response. However, there is a key difference between juiced fruits, such as orange juice, where the pulp of the fruit is removed, and smoothies, where the whole fruit is blended and consumed. The logic here is that by ingesting whole fruit, the digestive processes to break this down and release the equivalent free sugars is slower and results in a smaller glycaemic response. The issue is that recurrent elevated glycaemic response is a key risk factor for declining metabolic health, leading to conditions such as type 2 diabetes [2]. However, recent studies have suggested that consuming fruits in their blended form, such as smoothies, may not be detrimental for glycaemic control, and in some cases, may improve it by up to 57% [3, 4]. As adults in the UK do not currently eat enough fruit and vegetables, with only 33% of adults meeting the 5 a day recommendation [5], the potential for smoothies to increase fruit consumption whilst not adversely affecting metabolic health will require a change in public health advice.

There are now several key pieces of evidence demonstrating that ingesting blended fruit forms (compared to whole fruit) do not have an adverse effect on glycaemic response, and that this response can change depending on type and number of fruits ingested (Table 1). For instance, in healthy individuals, mango consumed whole or blended results in no change in glycaemic index (GI); [4]. However, the same study showed a blended mixture of mango, banana, passionfruit, pineapple, kiwi, and raspberries elicit a more favourable (lower) response than the same fruit consumed whole (GI 32.7 ± 8.5 vs 66.2 ± 8.2, p < 0.05). The latter mixed treatment was more reflective of smoothies that are commercially prepared and bought [4] and highlights the physiological response is the same or lower than consuming whole fruit (i.e., no negative effects). This has also been observed in data from another group that assessed apples (seeds removed) and blackberries, showing the incremental area under the curve (IAUC) was lower for the blended fruit compared to the whole fruit (850 ± 109 vs. 1269 ± 124, p = 0.005; [3]). Moreover, this trend has also been demonstrated in individuals with obesity and who are susceptible to glucose intolerance [6] In this latter study, individuals were given either whole or blended mango and raspberries or mango and passionfruit. Both blended fruit treatments showed a reduction in GI for individuals with a healthy BMI and those with obesity by 20–50% [6]. Although relatively few in number, and conducted in small groups of volunteers, these studies are all adequately powered to detect differences between treatments.