In January, the same month the United States announced its withdrawal from 66 multilateral organizations, China hosted leaders from Canada, Finland and Britain.

“The international order is under great strain,” Chinese leader Xi Jinping told British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, calling for efforts to “build an equal and orderly multipolar world,” as the two met in Beijing on January 29.

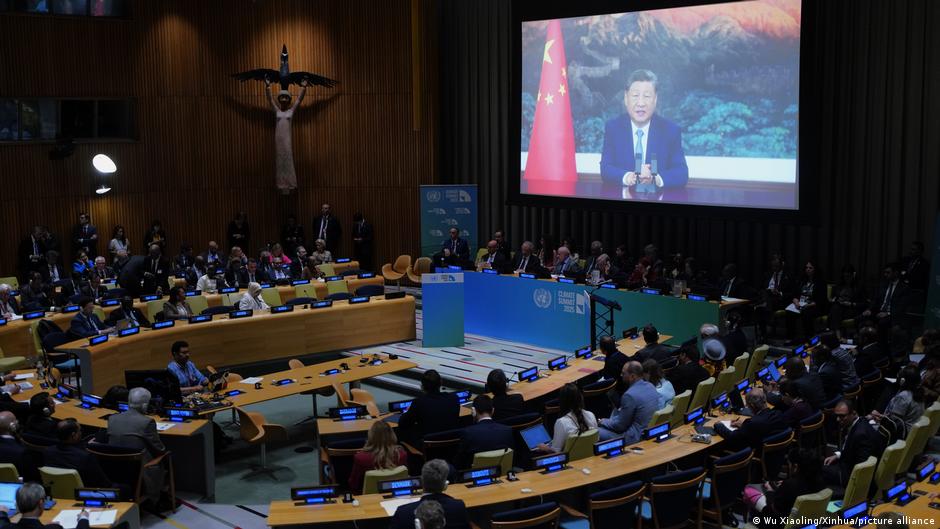

The message is not new in China’s diplomatic rhetoric, but it has grown more pronounced amid US disengagement from multilateral institutions.

The US is notably abandoning many initiatives focusing on climate change, labor and migration — areas President Donald Trump has characterized as “woke” initiatives “contrary to the interests” of the country.

At the same time, China remains a member of most of these multilateral organizations and gaining broader global recognition.

A recent international survey found that respondents across 21 countries, including 10 from the European Union, expect China’s global influence to grow over the next decade, according to the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“The power gap [between China and the US] was much clearer in the past… but now it’s getting closer and closer,” said Claus Soong, an analyst at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

“The US is still the most powerful nation in the world, but China is catching up very quickly,” he told DW.

China’s efforts to gather support from Global South

The Global South, which encompasses developing and emerging economies around the world, has long played a central role in China’s global strategy.

One of the most visible efforts is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013 as a vast infrastructure investment program to expand the country’s influence across Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America.

“A leader needs followers to support or to justify its leadership,” Soong said, adding that support from Global South is “the breaking point” for China in the face of Western containment.

Earlier this year, China released a series of data pointing to economic resilience despite growing pressure from the United States under the second Trump administration.

The figures include 5% economic growth in 2025 and a record trade surplus in the same year. The positive numbers were reportedly driven in large part by exports to non-US markets, particularly across Southeast Asia.

But Beijing’s strategy also comes with risks and limitations.

In recent years, China has scaled back the BRI from large, capital-intensive infrastructure projects to smaller, more targeted investments as financial risks rise and partner countries worry about taking on too much debt.

“Economy is a key question. How sustained was China’s economy? What else is China ready to give in to other countries?” Soong said.

Authoritarian coordination on the global stage

China’s close ties with Russia and North Korea have also raised concerns about the impact of deepening authoritarian partnerships on the world stage.

Xi met with Russian and North Korean leaders during a military parade in Beijing last year, underscoring Beijing’s political and security alignment with the two neighboring nations.

Sabine Mokry, a researcher at the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg, said each of China’s authoritarian partners serves a different purpose.

“The Chinese government is trying to assess what it can get from each regime,” she said.

One tangible outcome of such coordination can be seen during the United Nations General Assembly, as there has been an increase of China and its allies voting in alignment, particularly on the topics of human rights and Ukraine-related resolutions.

Still, Mokry noted that the partnership remains largely transactional, driven more by shared opposition to the US rather than by a value-based alignment.

“If there’s an opportunity to portray the fact that they work together, they will obviously take it. But on real substance, there is still deep-seated mistrust,” she told DW.

China not rushing to replace the US

Beijing has been leaning hard into a narrative in recent years that it is a responsible stabilizing power, especially contrasted with what it calls the US “hegemonism.”

But analysts believe Beijing’s ultimate goal is not to replace the US-led world order with a Chinese version. Instead, the main goal of the Chinese government seems to be that the Chinese Communist Party stays in power.

“It’s not a take-over-the-world kind of ambition,” Mokry told DW, emphasizing that China’s motive “always has to be seen from the lens of regime survival.”

She took Trump’s first presidency from 2016 to 2020 as an example, where the US also withdrew from a number of international organizations. Back then, despite expectations that China would step in to fill the leadership vacuum, Beijing largely refrained from claiming those positions.

Soong, the researcher at MERICS, shared a similar view.

He told DW that it is unlikely for China to take over leadership across all institutions the United States has exited, except where doing so aligns directly with its national security interests.

One example is China’s influence within the World Health Organization, where Taiwan — the island China claims as its own territory — remains excluded. The US has repeatedly cited the exclusion of Taiwan, especially during the 2019 COVID pandemic, as part of the reason for its withdrawal from the UN agency.

Pushing US out of Asia

Analysts say this selective engagement underscores Beijing’s broader aim — not to dominate the global system, but to reduce US influence in regions China views as strategically vital, notably the Asia-Pacific.

In recent months, China has intensified military activity around Taiwan and in the South China Sea, where tensions have flared with the Philippines over territorial claims from both sides.

“Beijing would be extremely pleased if they could just do whatever they want in Asia,” said Mokry, adding that the US engagement in the region remains so “fundamental” that “it’s not that easy to change.”

Edited by: Srinivas Mazumdaru