When the Chinese government launched the “AI+” initiative in August, it was widely perceived as a new economic stimulus. However, observers may have underestimated Beijing’s true ambition.

On October 10, senior officials and experts published a series of analyses in the official journal E-Government, offering the public its first comprehensive look at the initiative’s deeper strategic intent.

Far from being merely an economic policy, “AI+” is a decade-long national blueprint designed to propel China into a new phase of development – one that scholars describe as the age of “intelligent civilisation”.

By 2035, the vision is for robots to not only transform industrial production by replacing human labour in factories, but also to enter government institutions to assist in social governance, and potentially even become “companions and children” within Chinese households.

The “AI+” action plan aims for a multidimensional transformation, simultaneously reshaping politics, the economy, society, science and technology, and China’s stance in global affairs.

The government and its advisers are acutely aware of the significant risks involved and are proactively planning to mitigate potential negative impacts, including mass unemployment, the erosion of family structures, intensified human-machine conflicts, ethical upheaval and more social inequality.

Officials and experts forecast that by 2035, China could emerge as an unprecedented “land of infinite hope”.

“‘AI+’ represents the ultimate form of artificial intelligence development,” wrote Yi Chengqi, deputy director of the AI unit at the State Information Centre’s Big Data Development Department.

“Artificial intelligence will not only execute rules preset by humans, but will also be capable of forming new models, discovering new laws and even posing new questions in complex environments.

“Scientists will see infinite possibilities at the frontier of knowledge, enterprises will find infinite space for growth, the public will feel infinite hope for improved quality of life and the international community will explore infinite potential for win-win cooperation,” he added.

He Zhe, a professor at the Central Party School’s National Governance Department and secretary general of the National Strategy Research Centre, believes that lifestyles in an intelligent civilisation will be fundamentally different from today.

“In traditional civilisations, humans were the sole economic producers. However, in the intelligent civilisation era, as AI evolves from Narrow AI (ANI) to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and eventually Superintelligence (ASI), its role will shift from a mere auxiliary tool to an autonomous agent in production,” He wrote.

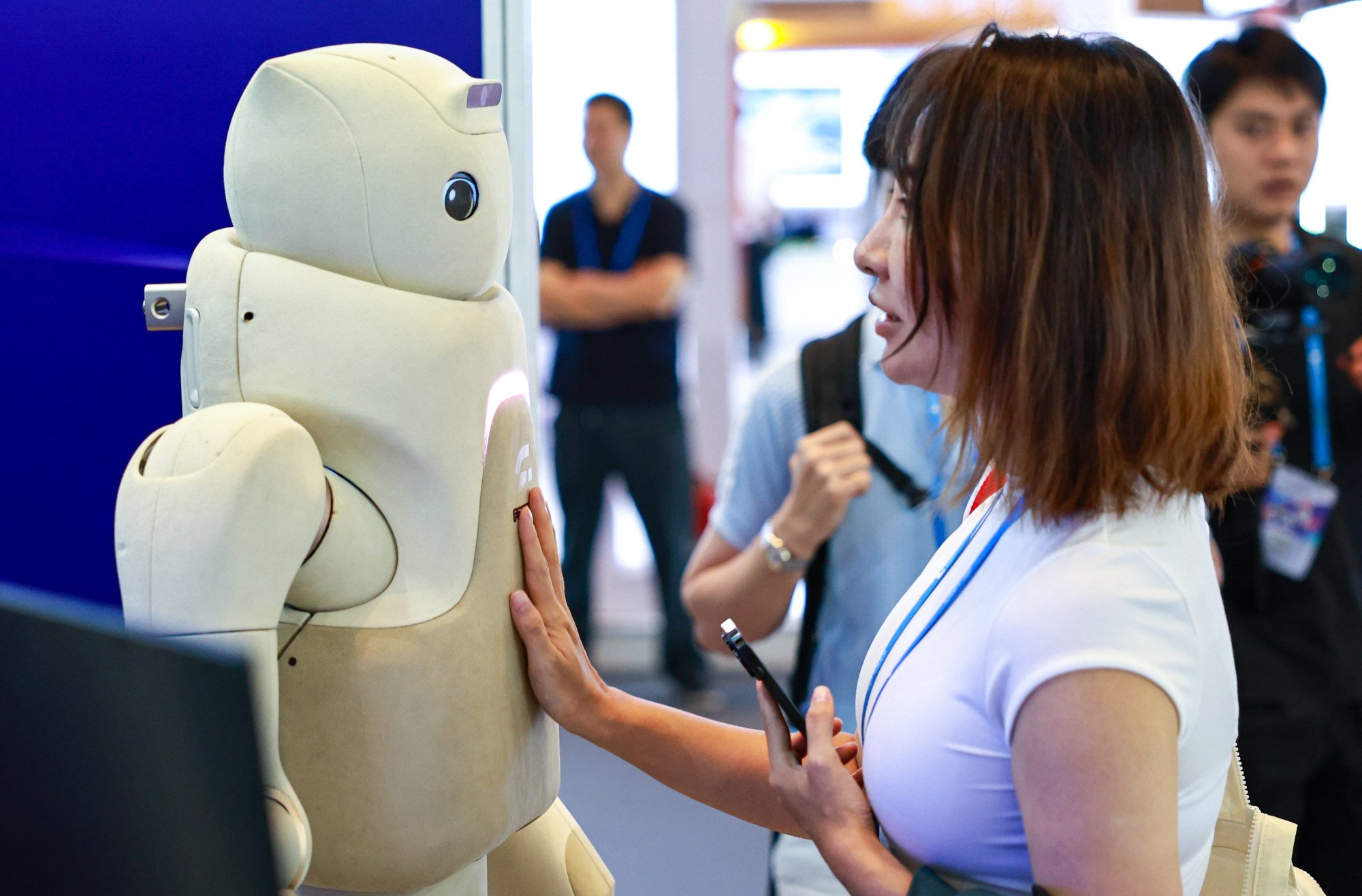

“It is foreseeable that humans will no longer be the only producers. With the development and widespread application of humanoid embodied intelligence, AI will no longer be confined to simple production tasks but will participate in complex production decision-making processes in human form.

“Thus, humans and AI will jointly constitute the producers of the intelligent civilisation.”

Moreover, robots will move far beyond factories.

“The continuous improvement of high-performance AI, especially embodied intelligence, will enable AI entities to participate in a vast array of human activities as social subjects,” He said. “This will fundamentally alter the traditional structure of a society composed solely of humans.”

Even family structures are expected to change.

“As individuals become more independent and AI permeates family life, traditional family forms will inevitably be transformed,” He wrote. “On one hand, more independent individuals will continue the trend of declining marriage and birth rates.

“On the other hand, AI will enter homes more fully, with intelligent pets, humanoid robot butlers, and even AI companions and AI children potentially becoming commonplace,” He said, using the Chinese word banlu, meaning partner or companion.

“Of course, a new trend may also emerge: as machines become ubiquitous and routine, the importance of authentic human-to-human relationships and stable social bonds may be increasingly highlighted.”

These official interpretations signal that the Chinese government has adopted a more proactive and holistic approach to AI compared to other places, and that it aims to lead the world into this new social paradigm.

This relative optimism is grounded in tangible progress. Thanks to the application of AI technology, China has made rapid advances.

For instance, China’s mass-produced humanoid robots, which at the beginning of the year could barely shuffle like an elderly person, were performing martial arts kicks and side flips akin to Bruce Lee just months later.

This momentum is partly due to China’s regulatory environment.

Unlike the United States, where AI development is primarily driven by corporations and lacks a long-term, government-mandated road map, or the European Union, which imposes numerous restrictions – such as banning AI for labelling individuals as high-crime risks or predicting consumer demand for production adjustments – China actively permits and even encourages these applications.

“Intelligent algorithms can precisely identify public needs, optimise resource allocation, and provide personalised, proactive services in fields like social security, healthcare, and transport,” wrote Liu Zhi, director of the State Information Centre’s AI unit.

“Intelligent early-warning models can achieve early insight and intelligent responses to financial risks, major disasters and mass incidents, greatly enhancing the precision and efficiency of emergency management.”

This represents a fundamental shift in human-system interaction. “Currently, the user-system interaction model is essentially ‘human-searches-for-platform’. Users must actively define their needs and take initiative through searches, clicks or inputs. Humans remain the initiators and masters of the interaction,” Liu said.

“The ‘AI+’ initiative completely overturned this logic, shifting to an ‘AI-finds-human’ paradigm. By analysing historical data, real-time context and latent intentions, AI systems proactively predict and deliver services.

“For instance, an intelligent assistant might automatically remind a user of a schedule or recommend a fitness plan based on biometric data. This proactivity not only reduces decision-making costs but also redefines service delivery: services are no longer passively summoned but become invisible companions embedded in our lives,” Liu said.

“This reflects a deep understanding of human-centred interaction – technology now adapts to human habits, rather than the other way around. This shift from ‘humans adapting to technology’ to ‘technology adapting to humans’ ensures technological development balances efficiency with user experience.”

However, such a profound transformation carries immense risks. “We must comprehensively consider the myriad activities and potential problems arising from AI’s widespread participation in human society,” He said.

“This includes the potential for mass unemployment and severe social polarisation after AI’s broad economic participation; the legal personhood of autonomous AI, including whether it has legal rights and who is liable for its actions; the further decline in marriage rates and the erosion of family ethics from AI’s integration into family life; and the increased systemic risks from AI’s involvement in public governance.”

Li Chongzhao, a professor at Yunnan University of Finance and Economics, pinpointed a critical governance challenge: AI is inherently cross-sectoral, yet existing government departments operate in silos.

For example, the National Health Commission oversees medical AI, while the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology manages industrial AI. Without coordination, this leads to “policy fragmentation” – conflicting regulations, incompatible data standards and disconnected systems. Li advocates for the creation of a powerful central coordinating body to break down these barriers and ensure policy synergy.

Wang Xiang, a researcher at Fudan University’s Digital and Mobile Governance Lab, warned that using AI in governance was a “double-edged sword”. He said that used well, it could achieve good governance, but when abused it could create a digital Leviathan.

This could manifest as pervasive state surveillance, creating a “digital panopticon” where citizens live under constant observation, or where systems like social credit are used to control behaviour, turning citizens into objects designed and manipulated by algorithms, according to Wang.

But Zhao Jingwu, a professor at Beihang University Law School, believes these risks will not impede AI’s rapid development in China.

Zhao noted a critical shift in governance philosophy. He said in the past, the government’s approach to new technology was primarily “risk prevention” – focusing on what AI could not do. Now, with technologies like large language models maturing, he said the focus had pivoted from “prevention” to “promotion”.

According to Zhao, the Chinese government’s new role would be less that of a regulator and more akin to a “parent” or “gardener”, focusing on creating a fertile environment for AI to flourish by providing data, computing power and real-world application scenarios. – South China Morning Post