China’s military purges replace institutional expertise with personal rule, increasing fragility and risks of miscalculation and conflict.

In a nutshell

- China is transitioning from a single-party regime to an autocracy

- The removal of Zhang Youxia raises the risk of war and errors

- Geopolitical setbacks and internal strains may accelerate Xi’s urgency

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

China is moving from a party-driven communist regime to one centered on a single person, removing seasoned experts from military leadership and making the country, its army and neighbors more susceptible to the whims and vision of President Xi Jinping.

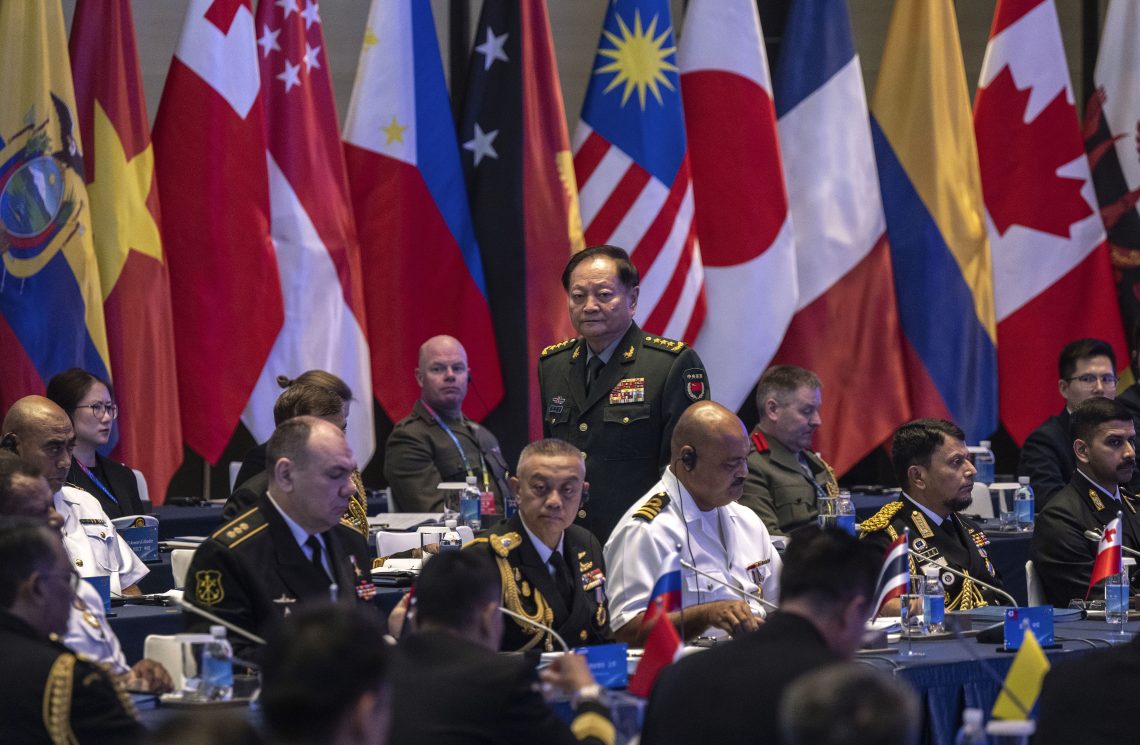

In late January, China’s defense ministry removed its top general, Zhang Youxia, and his peer, General Liu Zhenli, from the Central Military Commission (CMC), the highest military leadership body of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), placing both under investigation for potential corruption. Until the ousting, Mr. Zhang was a close ally of the president.

This follows earlier removals of experienced military personnel and, as a result, the CMC is now devoid of members with combat experience. The commission now comprises a sole military officer, General Zhang Shengmin, who is responsible for rooting out corruption, and Mr. Xi himself. The largest purge of Chinese officials since Chairman Mao’s era not only increases the chance of war but also risks calcification of the CCP under Mr. Xi.

By consolidating power, President Xi may be decreasing the likelihood of military coups; however, by narrowing the institutions to a small inner circle, he is also making the Chinese state more fragile. Personalist regimes are more likely than other forms of autocracies to initiate war, and for this reason, Mr. Xi’s purges at least temporarily increase the likelihood of an attack on Taiwan.

This comes as China’s position as a near-hegemonic rival to the United States is increasingly being called into question. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by Russia, China’s staunchest and most relevant ally, has turned into a quagmire. Recent American intervention in Venezuela and potential additional intervention in Iran are set to reduce Beijing’s access to oil. Iran’s performance in its war with Israel, the Trump administration’s “Operation Midnight Hammer” and Greenland set to host additional NATO defenses in the Arctic all place Beijing in a significantly weaker position than it was in after the U.S. weakened its own position by withdrawing from Afghanistan in 2021.

The U.S. defense department had previously assessed that China’s armed forces, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), would be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. With its most experienced generals swept away, President Xi consolidating power and a deteriorating geopolitical landscape for the CCP, Beijing’s risk tolerance and sense of urgency may be on the rise.

Zhang Youxia’s ouster lowers the threshold to war

General Zhang’s removal raises the potential for war due to two key factors. The first is that due to his experience modernizing China’s military and positioning it for great power conflict, his presence on the CMC brought a degree of professionalism. The second is that he was one of the few Chinese generals with combat experience; he fought in both the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979 and the Battle of Laoshan in 1984. Combined, these two factors ensured he would naturally act as a check of realism against uneducated strategic mistakes and military adventurism driven by political myopia.

The Sino-Vietnamese War started under circumstances that eerily resemble those of today. Hanoi’s pivot toward the Soviet Union and away from China during the Cold War led to conflict when Vietnam invaded Cambodia to remove Beijing’s proxy, Pol Pot. Notably, the 1979 war coincided with an internal fight for influence within the CCP between the future reformer Deng Xiaoping and holdover Maoists.

While both sides claimed victory, the 1979 war proved challenging for China’s military; its officers were using outdated techniques and materiel against a Vietnamese army that had accumulated decades of combat experience, namely against the U.S. Vietnam effectively occupied Cambodia until 1989. As short as the monthlong Sino-Vietnamese War was, the experience proved valuable to General Zhang’s career and the outlook he brought to China’s leadership.

China is shifting to a higher degree of risk tolerance and a higher likelihood of war.

After being admitted to the CMC in 2012, Mr. Zhang became director of the armed forces’ General Armaments Department. In this role, he worked to obtain new technologies, integrate command structures and develop new capabilities pertaining to all-domain combat including space. General Zhang also implemented anticorruption measures within the officer corps and emphasized combat readiness and technological capabilities in military and strategic planning. The new capacities he sought to implement were designed not only to establish China as a superpower but also to avoid mistakes learned in the Sino-Vietnamese War.

China’s position in the geopolitical landscape today is in flux, as it was in the late 1970s. Washington’s recent removal of pro-Beijing leaders like Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro and White House pressure on Iran and Cuba mirror the erosion of Chinese influence similar to that experienced by China in Cambodia. This may be heightening urgency for the Chinese president to attempt to secure Taiwan by force, running the risk of war with the U.S. as well.

General Zhang’s position before his ouster placed him at the boundary between military operations and geopolitical strategy. He reportedly differed with President Xi on the timeline for viability of a successful Chinese invasion of Taiwan, eschewing the 2027 deadline and favoring one around 2035. The removal of an experienced and cautious general like Mr. Zhang can indicate that President Xi is removing potential impediments to possible military strikes.

Historical precedent may indicate that a war on Taiwan is forthcoming, albeit not necessarily imminently nor successfully. Joseph Stalin’s purges of the Soviet Union’s officer corps from 1937-1938 contributed to Russia’s inability to stop the Nazi invasion in 1941. Stalin’s political lens led him to ignore the ample military intelligence that Russian generals offered, which warned of an impending attack.

While the purge of Soviet military expertise under Stalin proved disastrous in World War II, it also likely affected Moscow’s strategic calculation when it invaded Finland in November 1939. The then-inexperienced and politicized Soviet military failed to accurately understand Finland’s defensive capacity and ultimately forced Moscow into a peace settlement.

Similar dynamics preceded Japan’s entry into the war, when the modernist Control Faction of the Imperial Japanese Army purged the ultranationalist Imperial Way movement from the officer corps. In China today, Mr. Xi’s consolidation of power, the removal of relevant figures like Mr. Zhang, the resulting strategic implications and the military’s institutional awareness indicate China is shifting to a higher degree of risk tolerance and a higher likelihood of war.

Purges indicate a more fragile China

A robust body of research indicates that the consolidation of a personalistic dictatorship leads to war; furthermore, the ouster of Zhang Youxia is but one symptom of such a transition. Revolutions that produce risk-tolerant leaders and governments lacking strong institutional checks on personal power have been found to be more likely to lead to war. Similar work studying the course of roughly 200 dictatorships finds that a personalistic consolidation leads to erratic, warlike behavior that disturbs the rest of the world.

Personalization of politics is an increasingly common feature across all types of governments. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine came after years of personalistic consolidation by Vladimir Putin. Nicolas Maduro purged the military in 2024 while escalating rhetoric about annexing Essequibo in neighboring Guyana. While China’s military shakeup may make war more likely in Taiwan, it is also a signal that Beijing is not only transitioning from a single-party to sole-leader dictatorship, but also that it is becoming more fragile as an authoritarian system.

President Xi ended the practice of promoting an heir-apparent or “successor-in-training” at the 19th Party Congress in 2017. The following year, the National People’s Congress altered the country’s constitution to eliminate term limits for Chinese leadership. The CCP changed its own ideological orientation at the same time, by adding “Xi Jinping Thought” to its constitution. This enshrined President Xi as the party’s leader and his “Chinese Dream” as an operating principle for the state. In 2023, some China observers noted Mr. Xi’s efforts to rival the perceived prowess of Mao Zedong by amplifying elements of his own personality and branding himself as a political intellectual.

Read more by Dr. Ian Oxnevad

President Xi’s assembly of military loyalists earlier in his tenure and the subsequent removal of dissenting voices occurred alongside his consolidation of power within the CCP itself. Both areas demonstrate China’s shift toward autocracy. For Taiwan, it is particularly troubling that the reabsorption of the island into communist China is a component of President Xi’s China Dream. In a 2021 speech at the CCP’s centennial celebration, he devoted an entire paragraph to retaking the island through “peaceful national reunification.”

Despite such peaceful rhetoric, Chinese armed forces have been conducting more robust military exercises around Taiwan since 2018, roughly concurrent with the removal of President Xi’s impediments to lifelong political power. By all counts, these factors signal China’s shift toward a more bellicose and personalistic form of governance, and by extension, a greater readiness to invade Taiwan.

Scenarios

Most likely: Consequences of power grab increasingly distract Xi

China’s shift from a functional single-party regime to autocracy in practice is not a new phenomenon; it began around 2018. The continued hardening of China’s power around President Xi, the reshaping of institutions, the removal of generals and other developments within the CCP and politburo indicate a new phase of power consolidation. While regimes controlled by one person render policy more erratic, less constrained and more likely to enter into conflict, what is happening in Beijing does not necessarily mean that war is imminent, nor does this guarantee a Chinese victory if it were to invade Taiwan.

Imminent war is less likely than the continued concentration of power for a few main reasons.

International conditions conducive to a likely Chinese victory in Taiwan are not what they were three years ago. The Trump administration’s actions in Venezuela and Operation Midnight Hammer in Iran have helped reestablish American credibility after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. These actions have similarly curtailed Beijing’s network of friendly states needed for robust access to cheap oil. Russia’s long-term viability as a global military power is now being called into question due to Moscow’s performance in Ukraine.

Domestically, China faces macroeconomic instability, a demographic cliff and increasing civic discontent over the country’s future. As a result, President Xi’s consolidation of power puts him on a collision course with crises for which it will be difficult for him to deflect blame.

In sum, the more likely scenario is an increased personalization of China’s political system, which will divert attention from a competent invasion of Taiwan.

Less likely: An imminent and successful war on Taiwan

A less likely scenario that would be high-impact if it occurred is a near-term war with Taiwan. An imminent and successful Chinese war on Taiwan is less likely than the above scenario due to the uncertainty now instilled within the armed forces as a result of Zhang Youxia’s removal. The removal of experience from the PLA as an institution will make the organization less effective, but nonetheless more prone to strategic and operational mistakes. The likelihood of lapses of judgement, including an imminent preemptive war, are increased by the removal of prudent military advice from the top of China’s power structures.

As it stands, the CMC is now composed only of President Xi and one anti-corruption officer. Corruption can be detrimental to military preparedness and performance; yet mere allegations of corruption can be used as a cause to eliminate perceived political opponents. This signals increased paranoia, a greater likelihood of miscalculation and ultimately, war.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.