On the night of Feb. 8, when Bad Bunny turned the Super Bowl halftime show into a gleaming, Spanish-language valentine to Puerto Rico, Donald Trump did what he tends to do when the culture changes without asking permission: He complained, in public, that it was “absolutely terrible,” an affront, a mistake, an embarrassment. A year and a half earlier, at a Trump rally, comedian Tony Hinchcliffe had tried a different method of cultural correction, calling Puerto Rico a “floating island of garbage,” a line that briefly made the campaign look like it had accidentally booked the internet’s worst uncle as a warm-up act. If you want a quick index of the Trump era’s aesthetic project, it is this: grievance presented as taste, and taste enforced as grievance.

The novel twist is that Trump’s most useful cultural intermediaries have not been network anchors or newspaper columnists but men with microphones and a class clown’s contempt for status quo. They are comedians, comedy interviewers, comedy talkers. Their signature achievement has been to convert politics into hangout material and then to insist, sincerely, that nothing political happened. This alibi held for years because comedy has always depended on plausible deniability. But podcasts changed the scale of deniability. They turned the loose riff into a mass medium.

With their tens of millions of subscribers, “manosphere” shows — a circle of pals that includes such Trump-amenable comics as Hinchcliffe, Joe Rogan, Theo Von and Andrew Schulz — are not a cultural footnote. They are an infrastructure map. The key point is not the precise listener count. It is the rhythm: weekly, habitual, intimate. Politics becomes less like a lecture and more like a recurring voice in your ear.

Sydney DeMets, a fifth-year Ph.D. student at the University of Washington who studies podcast networks and misinformation, described the medium’s advantage less as media theory than a statement of physics. “Podcasts are incredibly persuasive,” she says, because “they induce the parasocial phenomenon” and “trigger a lot of feelings of intimacy and trust.” In her account, the listener does not merely consume content. The listener builds a relationship. After enough hours, disagreement feels like betrayal.

This is how political influence arrives disguised as personality. Rogan’s show rarely sounds like instruction. It sounds like curiosity. Von’s show rarely sounds like ideology. It sounds like a shaggy, melancholic tenderness, a refusal to be pinned down. Schulz’s show is never doctrine. But it does sound like swagger, the confident relief that comes from saying what polite people do not. Their political effect comes out of something far more subtle than persuasion; it’s permission. They do not tell their audiences what to believe so much as they suggest what it is acceptable to laugh at, to dismiss, to view as performative, or to regard as “just the media” doing its predictable thing.

By 2024, campaign professionals recognized what they were watching. Vox described the election as a contest in which podcasts became kingmakers in the sense that the candidates went where the audience already was. Trump appeared on more than a dozen manosphere podcasts, including those of Rogan, Von and Schulz. In an analysis of pro-Trump YouTube and podcast figures, Bloomberg framed these platforms as a mobilization engine aimed particularly at men who do not otherwise move through civic life as “voters.” To say that such shows “swung” an election is too tidy. Causality in politics rarely behaves. But it is reasonable to say that they shaped the emotional weather in which politics was experienced, and that weather matters, especially for people whose political identities are weak and therefore movable.

The hangover arrives when permission meets governance. Once Trump returned to office, the comedy-podcast ecosystem began to display a new and telling discomfort: not always with Trump as symbol, but with Trump as administrator. It is easier to flirt with the outsider narrative when the outsider is not running the Department of Homeland Security.

Von’s recent rupture with the administration is instructive because it is less ideological than existential. When DHS posted a deportation-themed video that used a clip of Von without his consent, he objected publicly and demanded it be taken down, saying his views were “more nuanced” than the propaganda suggested. Later, Rogan and Von discussed the incident as a kind of violation: not merely of copyright or consent but of persona. The DHS video drew an estimated 30 million views before its removal, reportedly rendering Rogan furious. The episode revealed what the medium had been hiding: These shows are not merely entertainment products. They are trust banks. And governments borrow trust where they can.

Schulz’s retreat has been much louder. Talking to Charlamagne tha God on a Jan. 31 episode of their Brilliant Idiots podcast, a rattled Schulz said the fatal shooting of Alex Pretti by ICE agents in Minneapolis was his “breaking point.” A reorganization had occurred inside his head: Objecting to Trump was no longer “liberal catastrophic thinking” but “very reasonable, nuanced criticism of the administration.”

A comedian who was once a cultural validator becomes, instead, a cultural scold. That shift is small in theory and large in practice. It changes what the audience is permitted to say out loud. Even Rogan, the sun around which this ecosystem rotates, has occasionally sounded as if he is trying to reverse-engineer his own influence. He has criticized the administration’s tactics and questioned the wisdom of policies that seemed designed more for spectacle than for governance. Rogan’s dissent, when it comes, arrives in the same register as his endorsements: a long conversation, a raised eyebrow, a suggestion that the official story is not fully credible. In this universe, skepticism is the closest thing to morality.

The cultural problem for Trump is that comedy does not sour politely. It moves from fascination to boredom, from indulgence to contempt. And contempt is contagious. In the past, comedians helped Trump by treating him as a kind of entertainment object: a chaos agent, a disrupter, a man too crude to be controlled by the usual institutions. Now, those same institutions are being used openly, aggressively, sometimes carelessly. When the government begins borrowing podcast clips for enforcement hype, the bit starts to look less like comedy and more like complicity.

This is why the Hinchcliffe episode matters. When he called Puerto Rico “a floating island of garbage,” the backlash was swift, not only because the line was ugly but because it demonstrated how the comedy-adjacent right mistakes insult for candor. It was a preview of the aesthetic logic of Trump’s second term: Provoke the minority group, relish the scolding, declare victory over “mainstream media.” The trouble is that this logic becomes exhausting when it no longer is a campaign style but an administrative style. Even people inclined toward grievance can tire of being governed by tantrum.

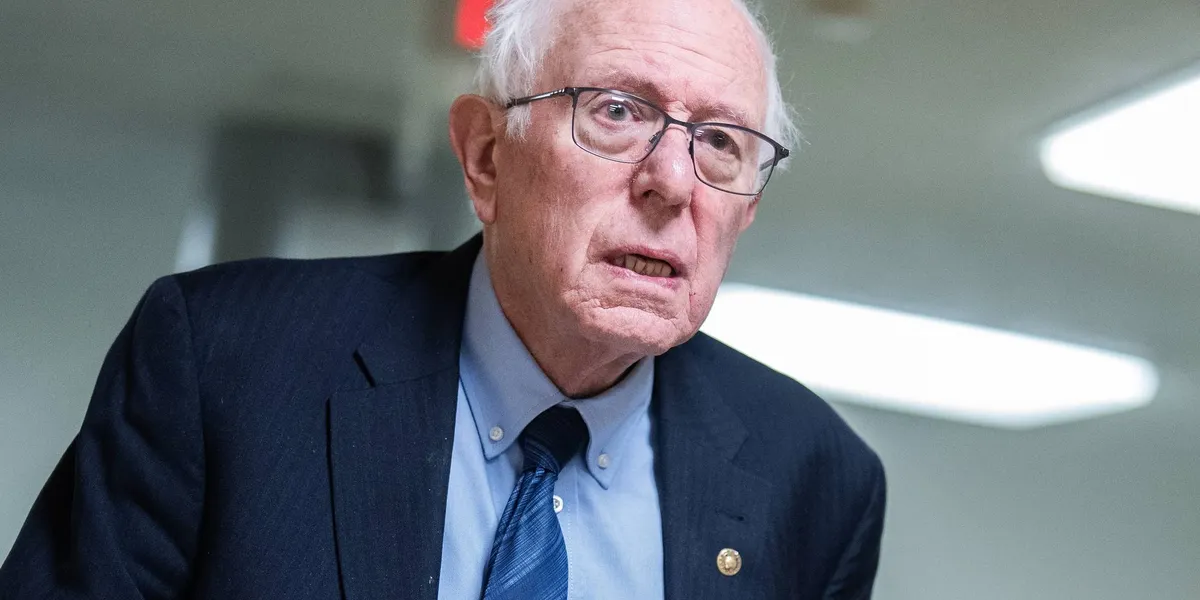

Tony Hinchcliffe’s callous joke about Puerto Rico at the 2025 Republican National Convention revealed how the comedy-adjacent right mistakes insult for candor.

Peter W. Stevenson/The Washington Post/Getty Images

It is unclear how much “buyer’s remorse” among podcast comedians can affect elections. But while the shows may not deliver votes directly, they do deliver marching orders indirectly, by regulating mood. In an electorate where many marginal voters are not ideological but ambient, the people who define what is embarrassing, what is acceptable, what is “too far” and what is “just noise” can have outsize power.

Trump can survive contempt from newspapers. He has survived it for years. What he cannot easily survive is contempt from the people who made him feel, to millions of listeners, like a permissible choice. The hangover is spreading: not a sudden moral awakening, but a curdling, a fatigue, a dawning sense that the joke kept going long after it stopped being funny.

The uncomfortable truth is that if the country really is becoming disenchanted with Trump, it will not be a committee of elders that announces it. It will be a handful of comedians, talking into microphones, deciding that the bit is no longer worth the cost.

This story appeared in the Feb. 11 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.