I love to talk about password managers because, in this age, it’s one of the ways our personal information is protected. Although I lean toward open-source offline managers, I never recommend a phone’s built-in manager. However, the option I never recommend is using your phone’s built-in password manager.

I understand that it’s a convenient option, but beyond that, there aren’t many other good reasons to stick with it. I dug deep into how they work, how they suit real-life scenarios, and their limitations seem to outweigh the convenience or platform preference that draws us to them.

Tying vaults to platform accounts makes that account a single point of failure

Your passwords are tied to your Apple ID or Google account

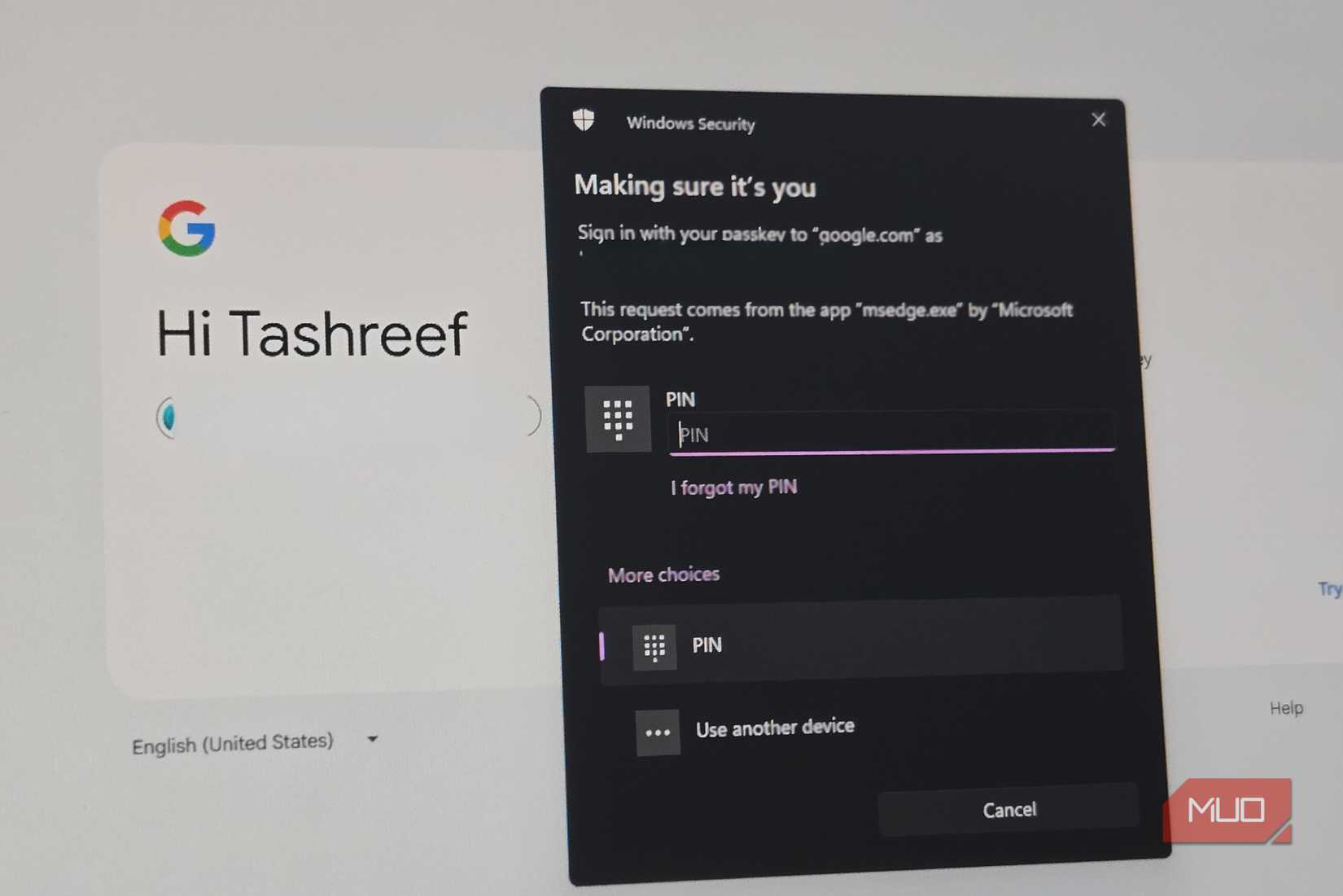

If you depend on iCloud Keychain or Google Password Manager, access to your entire password vault depends on continued access to your Apple ID or Google account, not just the security of your mobile device. This is because both examples are cryptographically tied to your platform identity.

What makes this a problem is that it exposes you to failures unrelated to hacking. You can be instantly cut off if there are automated fraud flags, terms-of-service suspensions, failed multi-factor authentication attempts, or a locked recovery process. These may be temporary lockouts, but even five minutes without access is enough to create real panic.

Apple implements Advanced Data Protection, which shifts recovery to trusted contacts or devices. But this further deepens dependency, and you may lose access entirely if the devices or contacts aren’t available. This differs from most dedicated password managers, which keep vault access independent of device vendor accounts.

End-to-end encryption exists, but you cannot independently verify it

You’re trusting claims you can’t audit or meaningfully validate

Apple’s Advanced Data Protection enables end-to-end encryption for iCloud Keychain; Google performs on-device encryption before syncing. So far, this is good news. Both point to strong encryption implementations.

However, the truth is that these are claims you must accept on trust. For both organizations, we don’t know of any published threat models, reproducible builds, or independently verifiable audits of the password vault implementations.

The default keychain configuration for Apple allows you to recover accounts using keys that Apple provides. With Google, encryption keys are derived from the account. But again, in both cases, there are no publicly available, fully documented technical details. There’s also no way for external researchers to independently validate how they work since both are closed source.

This is another area where dedicated password managers outperform built-in managers. They periodically publish third-party audits, cryptographic whitepapers, and bug bounty scopes. And while the point isn’t whether Apple or Google can read passwords or not, it’s simply a note on encryption that exists and encryption that can be verified.

Physical device access collapses the security boundary

Once your phone is unlocked, your entire vault is one step away from being accessed

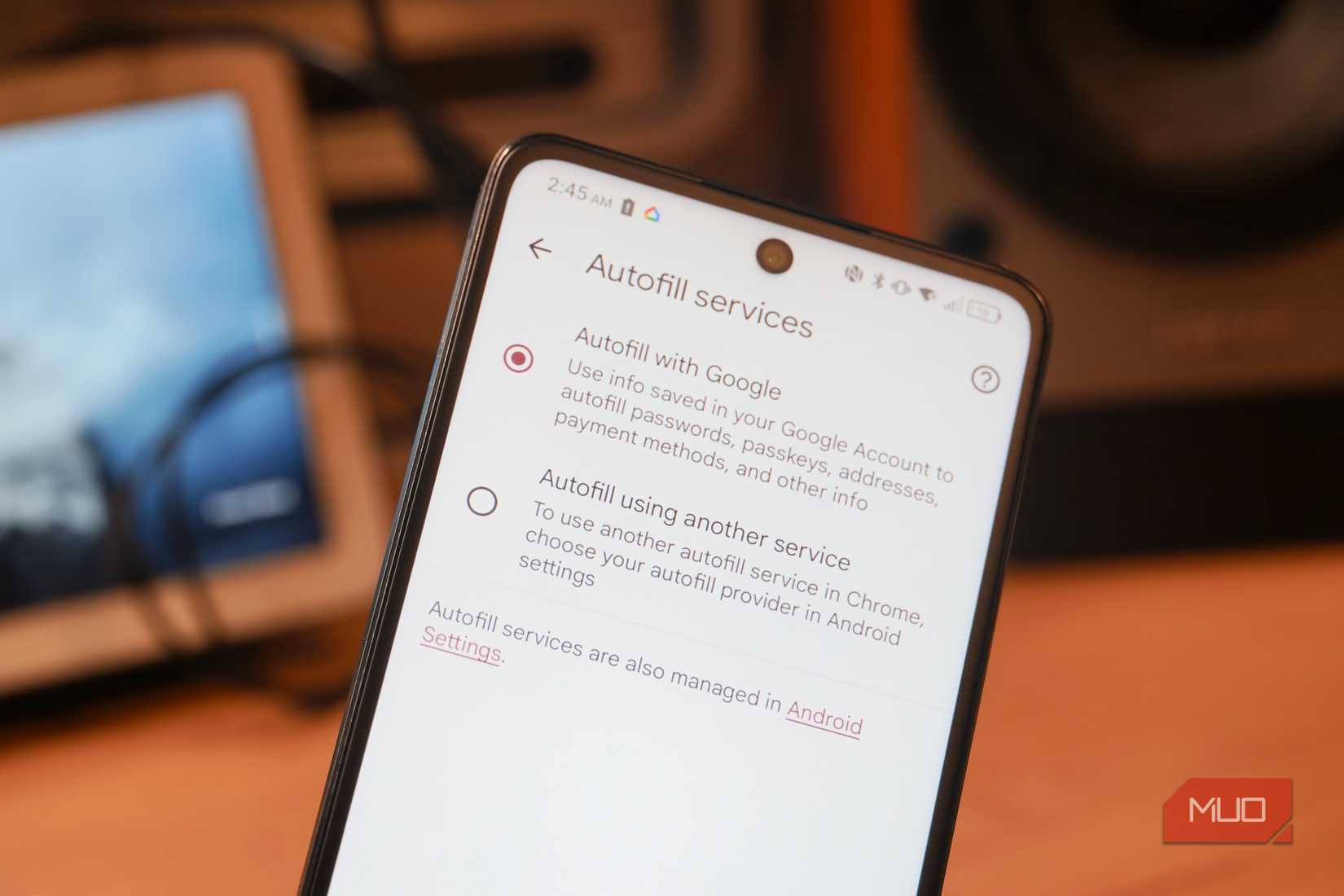

With built-in password managers, the assumption is that once your phone is unlocked, you must be the legitimate user. You get password autofill on iOS immediately after Face ID or Touch ID succeeds. There isn’t a separate implementation for vault timeout or a master password. On Android, there is additional authentication. However, by default, you still get device unlock behavior.

This architecture on mobile phones makes it a risk for real-world use. If your phone is unlocked, then stolen, your vault can be accessed without any other barrier. In certain contexts, Apple’s newer stolen device protections come in handy, but these rely on location and behavior and don’t completely fix the problem.

A dedicated password manager typically includes separate authentication after a device is unlocked. This makes it far safer for everyday situations.

Migration and exit are technically possible, but practically hostile

You can leave, but the system is designed to discourage it

On both Android and iOS devices, you can export saved passwords. However, if you’ve actually tried it, you’ll realize that it’s a friction-heavy process. The process on an iPhone requires navigating deep settings, locating the password section, and exporting a CSV file. On Android, you typically rely on Google Takeout, and this isn’t obvious either.

But even the exported CSV file poses security risks because it is unencrypted. To maintain some level of safety, you must manually keep them secure and delete them after the process. It’s possible to lose important metadata during this process. Also, re-importing this data into a dedicated manager will require manual cleanup because there’s no standardized export format.

This is a user-hostile UX pattern that simply raises the cost of switching from a phone password manager to a dedicated password manager. Regardless of the constraints, you must try every option to back up your passwords.

Advanced security signals are minimal or reactive

You get basic alerts, not proactive credential intelligence

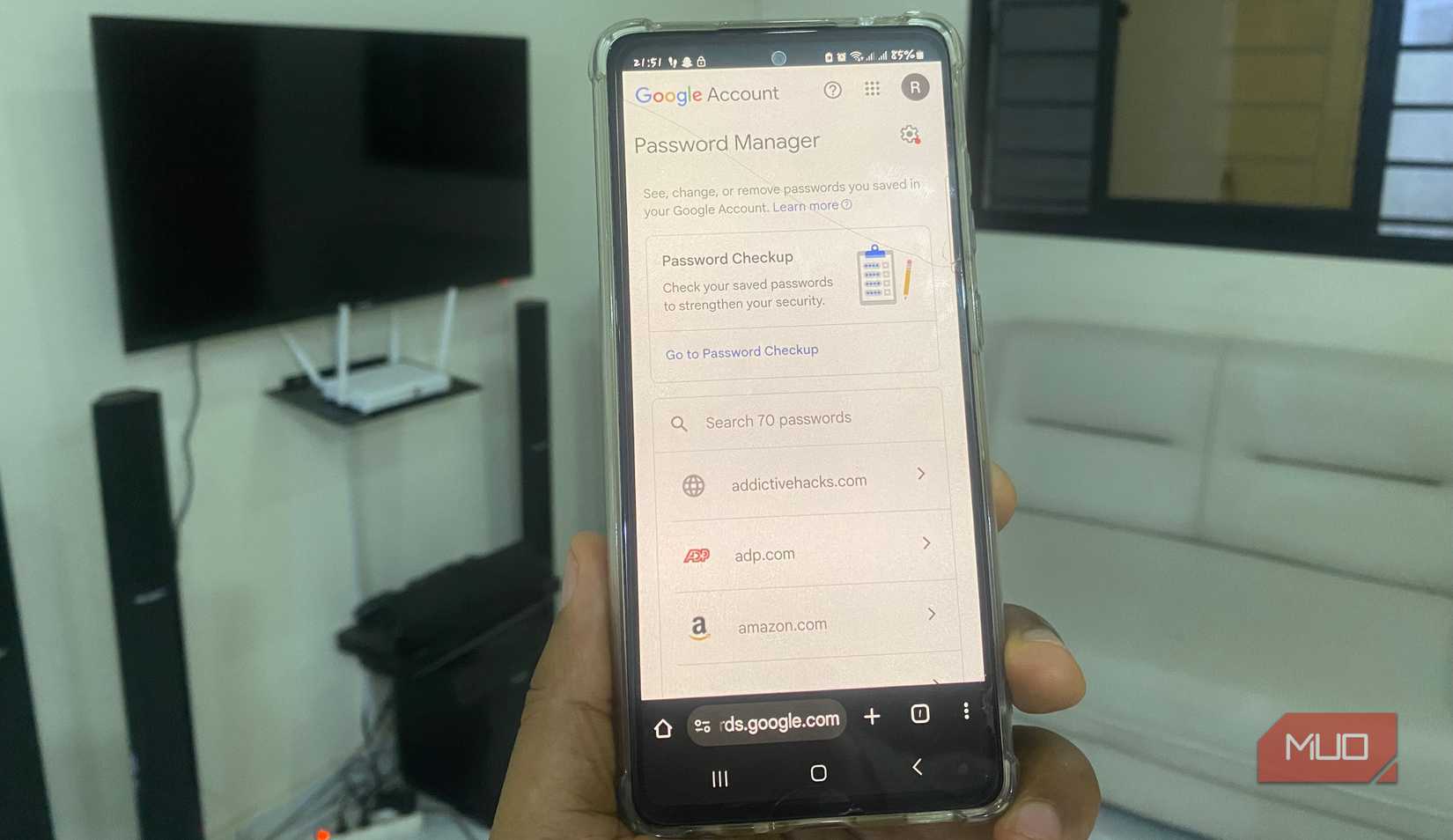

Built-in password managers offer basic security signals like reused password warnings and alerts for credentials compromised in data breaches. iOS uses Apple’s own breach data, and Google uses Password Checkup to offer similar monitoring.

What phone password managers lack is a deeper, proactive analysis. So, you don’t typically get password age tracking, strength scoring, or identification of stale credentials. Also, built-in password managers don’t show which compromised accounts pose the biggest threats. If you have years of accumulated logins, these extras are non-negotiable.

This is far behind dedicated password managers that typically offer dark web monitoring and continuous health reports. They even give actionable insights through tools like Have I Been Pwned.

Secure sharing and delegation are fundamentally underserved

Modern digital life requires shared access, and built-ins aren’t built for it

The modern account requirement has made secure password sharing more than a niche requirement. Couples manage joint finances, and families share streaming services. These are not things that your phone’s built-in password manager does well.

On iOS devices, we have password sharing through Family Sharing, and with Google Family, there’s some limited sharing. However, in both cases, these remain blunt instruments. Sharing can be all-or-nothing, typically lacks view-only permissions, time limits, and audit logs. These options don’t allow you to see who accessed what, and there isn’t a safe way of sharing with someone outside the ecosystem.

Sharing is an advanced feature on dedicated password managers, and they offer granular permissions, as well as revocation, access logs, and cross-platform sharing.

7 Common Password Manager Issues and How to Fix Them

If your password manager isn’t working properly, there are some handy, easy fixes you can try.

So, is the convenience really worth it?

Your phone’s built-in password managers are not insecure, nor are they poorly engineered. The problem is that they’re designed to serve an ecosystem. This is why they’re not ideal for handling data or accessing credentials daily.

The reason we use dedicated password managers is that our daily realities have outgrown a convenience-first design. They offer the best service, taking into account device loss, account lockouts, coercion, and human error. As a security measure, I stopped allowing my browser to handle my passwords: it’s time to do the same with our phones.