The United States formally determined in January 2021 that China’s actions in Xinjiang constitute genocide, according to the US State Department.

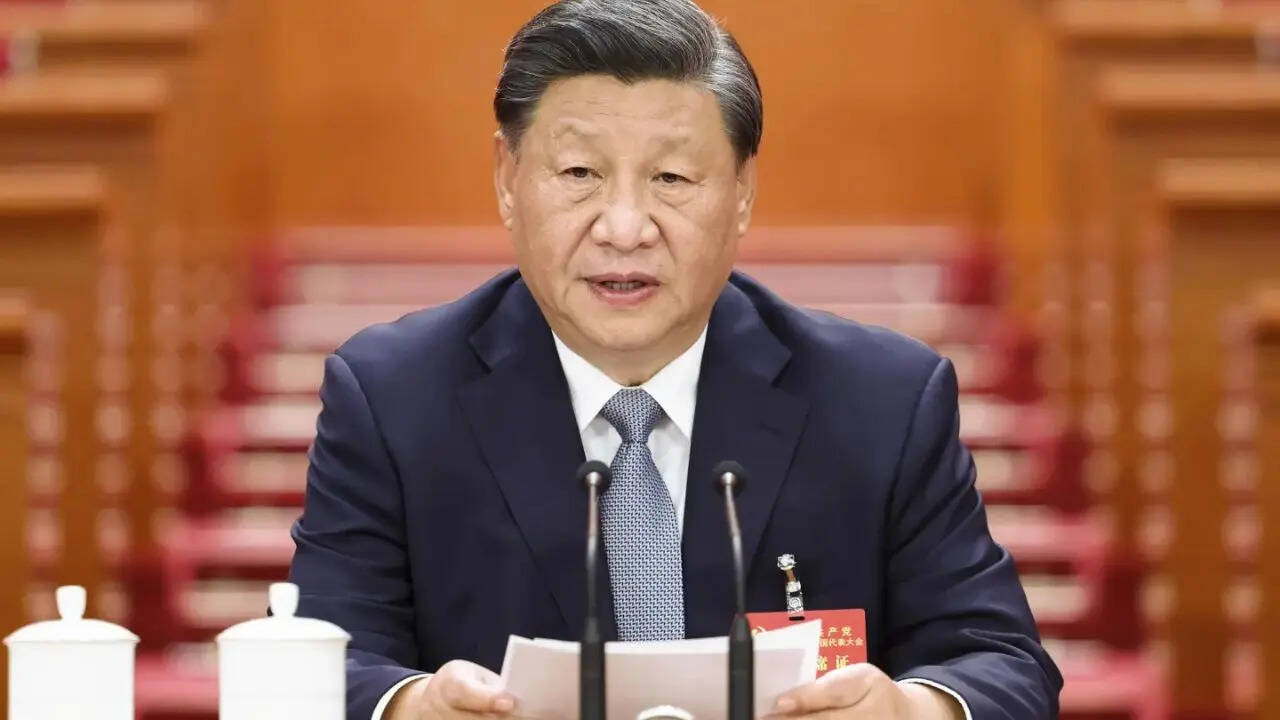

Photo : AP

Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Urumqi in late September to mark the 70th anniversary of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, according to Reuters. The trip was heavily publicised by state broadcaster CCTV, which presented images of Xi speaking to cadres, schoolchildren and residents under the banners of “ethnic unity” and “national rejuvenation.” Reuters noted that the Chinese leader praised “stability and progress” achieved under the Communist Party’s rule.

However, human-rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch have stressed that these celebrations conceal systemic abuses, including mass arbitrary detention and restrictions on religious practice. In its 2024 report, Human Rights Watch described Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang as a “comprehensive system of repression” designed to assimilate Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. Amnesty International has similarly called the situation “a dystopian nightmare,” citing testimonies of former detainees who detailed indoctrination sessions and coercive labour.

Camps, Detentions And Genocide Accusations

Investigations by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) and the BBC have estimated that over a million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities have been held in detention facilities across Xinjiang since 2017. Satellite images published by ASPI showed the expansion of high-security compounds, while the BBC obtained leaked documents describing internal Party directives on the management of detainees. China has consistently denied that these facilities are “camps,” instead calling them “vocational training centres.”

The United States formally determined in January 2021 that China’s actions in Xinjiang constitute genocide and crimes against humanity, according to the US State Department. The bipartisan Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) also concluded in 2020 that Beijing’s policies met the international legal threshold for atrocity crimes. China’s Foreign Ministry rejected these claims, calling them “the lie of the century,” but the designation has underpinned targeted sanctions and forced-labour import bans.

Forced Assimilation And Cultural Erasure

According to a 2023 Human Rights Watch report, Beijing has prioritised Mandarin instruction in schools while sidelining Uyghur language education. The group stated that children in Xinjiang are increasingly separated from their families and placed in state-run boarding facilities where “patriotic education” is emphasised. Scholars such as James Millward of Georgetown University have argued that these measures represent “cultural erasure” of Uyghur identity.

Religious practice has also been severely restricted, with the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) documenting bans on fasting during Ramadan and the demolition of mosques. A 2022 investigation by The Guardian reported that over 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang had been damaged or destroyed since 2017. The Chinese government maintains that these actions are part of counter-extremism measures, but rights groups describe them as an assault on cultural heritage.

Forced Labour And Global Supply Chains

Reports by the Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region and by the Associated Press have linked Xinjiang’s labour transfer programmes to global cotton, textile and solar supply chains. A 2020 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute found that more than 80,000 Uyghurs had been transferred to factories outside Xinjiang under conditions that “strongly suggest forced labour.” The Associated Press has also documented Uyghur labourers in tomato-processing plants whose products end up in international markets.

In response, the United States enacted the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act in June 2022, banning imports from Xinjiang unless companies can prove goods were not made with coerced labour. The European Union has proposed similar measures, with lawmakers citing investigations by the New York Times and Bloomberg that exposed forced-labour links in solar panel production. China’s Ministry of Commerce called these sanctions “economic bullying” that would “hurt global supply chains.”

Geopolitics And Beijing’s Defensive Posture

Xinjiang’s strategic importance lies in its location at the crossroads of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, as highlighted by a 2023 report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The region borders Central Asia and Afghanistan, making it critical to China’s energy pipelines, mineral resources and overland trade routes. Xi’s speeches in Urumqi emphasised that “security in Xinjiang is vital to the overall security of the nation,” according to Xinhua.

Despite growing international condemnation, Beijing has doubled down on its security policies in Xinjiang. In 2022, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said that the abuses in the region “may constitute crimes against humanity,” but China dismissed the UN report as “based on disinformation.” Analysts at Chatham House argue that Xi’s public visit reflects not only internal control but also a defiant signal to the West that Beijing will not bow to external pressure.