Now China no longer needs Germany—and Germany wants a divorce.

For the first time in decades, German businesses and politicians are questioning the unfettered free trade that turned the country into an industrial powerhouse. Its manufacturers want protection from cheaper, faster and increasingly better Chinese rivals.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said last month that Berlin would protect domestic steelmakers from Chinese competitors. His government has tightened a ban on Chinese components in mobile-data networks and it has signaled support for “buy-European” clauses for public tenders.

In its first meeting in November, Merz’s newly created National Security Council addressed the strategic risks of China’s dominance of several critical minerals. It is now working on diversification measures, according to a German official.

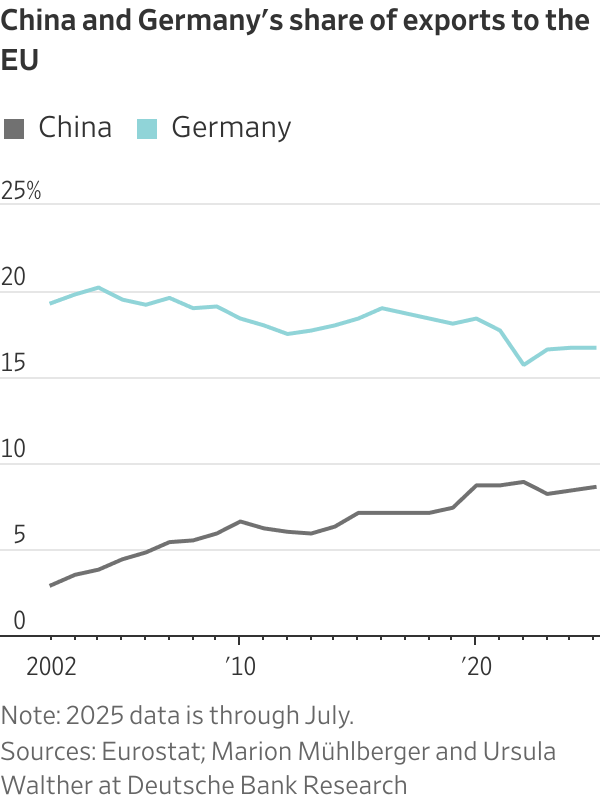

Germany’s estrangement from China has been in the making for some time. Helped by low production costs, a weak yuan and state subsidies, Chinese manufacturers are increasingly leading in sectors that German companies dominated until recently, not only in China but also in other markets, including in Europe.

Its timing, though, has much to do with President Trump. A wave of cheap Chinese goods, from chemicals to car parts, began washing over Europe this year after bouncing off the U.S.’s new tariff wall, economists and business executives say.

As a result, a country that once was a beacon of economic liberalism is itself warming to tariffs, regulatory barriers and other protectionist measures German politicians and executives had long criticized as misguided or, worse, “French.”

“Germany is moving and becoming aware of the imbalances that also affect it,” French President Emmanuel Macron told French daily Les Echos recently after his trip to China. “China is hitting the heart of the European industrial and innovation model.”

The fading of Europe’s most influential free-trade voice shows how the global economy is fragmenting in the face of big-power competition between the U.S. and China and a backlash against globalization led by ascending populist forces in the West.

Germany’s pivot has yet to reach all corners of its economy and government. The larger a company’s exposure to China, the harder it is for it to reverse course. Some carmakers and chemicals producers are still investing heavily in the country. German politicians are also watching over their shoulders as allies oscillate between confronting and pacifying China.

The direction of travel is becoming clear, however, originating among businesses, later percolating through the country’s influential lobby organizations and, more recently, government.

The Federation of German Industries fired the opening shot in 2019, when it ditched its China-friendly position in a report to call the country a “systemic competitor.” This year, the VDMA federation of machinery makers—export-oriented business-to-business companies that form the backbone of Germany’s economy—accused China of unfair competition. It has called for antidumping measures and sanctions against Chinese exporters that ignore European legislation.

“We are free-traders, but unfair trade policies cannot be tolerated any more,” said Oliver Richtberg, VDMA’s head of foreign trade. “If China doesn’t play fair, we have to make them.”

The government, in addition to a new economic-security strategy it plans to publish next year, is working on “projects that address the increasing economic, technological and security policy risks in dealing with China,” the German official familiar with the deliberations said.

German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul, speaking this month during his first trip to China, said European companies needed better access to the Chinese market and to resources the country produces.

“The change of tone…is quite remarkable,” said Andreas Fulda, professor of political science at Nottingham University and author of a recent book on Germany and China. “Now we need actual policies to incentivize derisking and reshoring.”

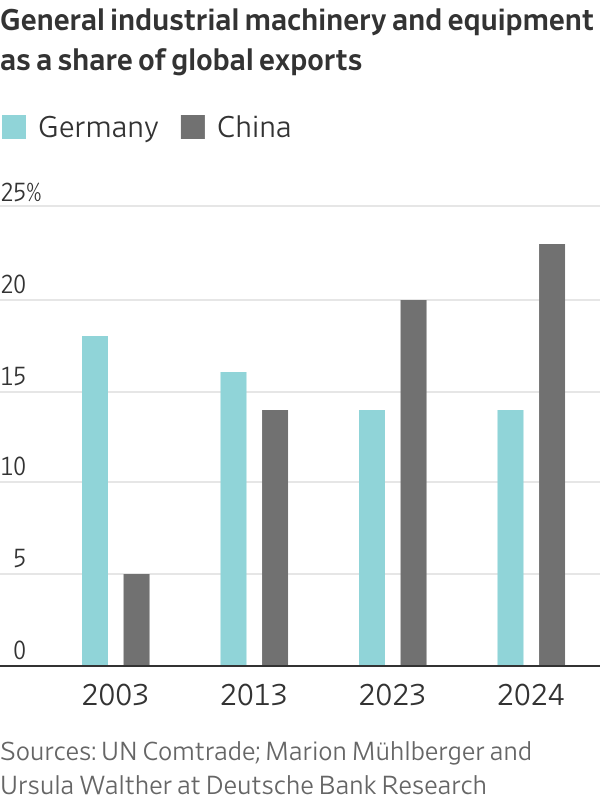

China’s graduation from buyer to maker of investment goods has been meteoric. Between 2019 and 2024, Germany lost its global market-share lead to China for power-generation equipment and machinery, according to data in a coming report from Rhodium, a think tank.

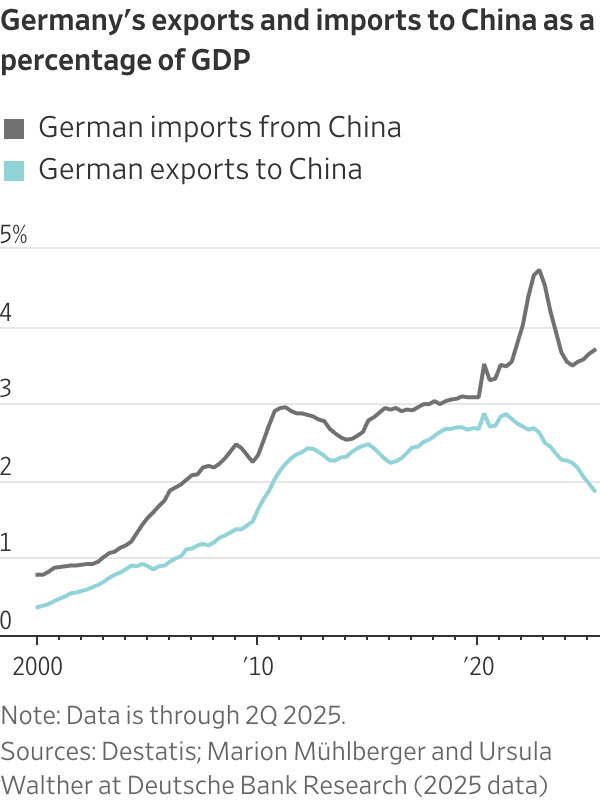

Germany’s lead in chemicals and road vehicles is now paper-thin and it is trailing far behind China in the electrical-equipment market. This year for the first time, Germany imported more capital goods from China than it exported there.

The trend is accelerating: In the second quarter of 2025, imports of manual gearboxes from China rose almost threefold, according to the German Economic Institute think tank. German carmakers have seen their share of the Chinese market drop from half to a third in two years.

Total German exports to China have fallen by a quarter since 2019 while imports rocketed. Germany’s trade deficit in goods and services with China is on track to reach a record 88 billion euros this year, equivalent to around $102 billion, according to German government figures.

This has left deep scars. Germany’s manufacturing output has fallen 14% since peaking in 2017. The industrial sector has shed almost 5% of its jobs since 2019, according to consulting firm Ernst & Young. The auto sector has lost about 13% of positions over the same period.

One company feeling the heat is Herrenknecht. The family-owned business makes and operates some of the most sophisticated tunnel-boring machines in the world. The diggers, up to 62-feet high, are miniature factories that can munch their way through the toughest of rocks while laying pipes, cables and cladding as they go.

When China began its ascendance to world-power status, local authorities turned to Herrenknecht for their biggest infrastructure projects. Now, after a string of acquisitions, Chinese rivals dominate the global market.

“We are under growing competitive pressure, especially from state-subsidized Chinese vendors,” said spokeswoman Anja Heckendorf.

The company is now exploring new markets, such as India, and focusing on larger and more-complex projects. At the same time, it is calling for antidumping probes of Chinese rivals and for a “Europe First” approach to public tenders that would favor local vendors, Heckendorf said.

The pressures are coming to a head in one of Germany’s primary chemical-industry clusters, centered on the East German city of Leipzig.

The former coal-mining region was a cradle of Europe’s chemical industry in the 19th century thanks to big local coal mines, later becoming central to East German industry. The region closed the mines after the reunification of Germany and built a chemicals cluster powered by Russian gas. This year, Chinese chemicals have poured into Europe, growing their share of the market for polyamide 6, a plastic widely used across multiple industries, to 20% from 5% last year, said Vedran Kujundzic, chief commercial officer at DOMO Chemicals, a producer in the town of Leuna with about €1.3 billion in annual sales.

“They are a constant presence,” he said, adding that they offer 20% discounts to European producers on average.

Christof Günther, chief executive of one of Germany’s largest chemical parks, located in Leuna, said businesses are struggling to cope with a surge in Chinese imports.

“We feel that very strongly here,” he said. Businesses in the park can’t earn money and are cutting costs whenever possible, including jobs. “They can only hold out for a certain time.”

Dow Chemical recently said it would close two plants in the region and eliminate over 500 jobs. German chemical giant BASF and other producers have cut thousands of jobs across Germany in recent years while building up in China.

In Leuna, Finnish forestry company UPM is building a €1.3-billion biorefinery on the site of a former BASF plant that will convert hardwood into chemicals. These are more expensive than fossil-fuel based chemicals, said Executive Vice President Harald Dialer, but customers value high-end products in industries such as cosmetics.

Nearby, Stefan Scherer, CEO of Frankfurt-based chemicals producer AMG Lithium, is building a lithium refinery that could eventually supply one-quarter of Europe’s needs. But Scherer said German customers are spooked by higher prices.

This is why innovation alone won’t suffice to preserve Europe’s manufacturing capacity, said Dirk Schumacher, chief economist at Germany’s state-owned development bank KfW.

“We as a country need to decide what we are happy to source from China in the future and what we want to keep producing ourselves,” Schumacher said. “This could involve erecting barriers to protect strategically relevant sectors.”

“Europe is still open to Chinese investment, but [policymakers] want Europe actually benefiting in terms of know-how and jobs,” said Noah Barkin, an analyst with Rhodium. The question is whether China will agree to this—and if not, if Europe is willing to close its market to China.

Barkin says he can’t rule out Germany reverting to what he calls its “Shanghai syndrome”—preference for the short-term gains of appeasing China despite the long-term risks. This could happen if Berlin decides it needs a hedge against an unpredictable Trump.

Norbert Röttgen, a conservative lawmaker and foreign-policy expert, spelled out the dilemma. “We need to reduce our dependence on China,” he said. “But if the U.S. lets us down, that will have an impact on how we define our relationship to China.”

Write to Tom Fairless at tom.fairless@wsj.com and Bertrand Benoit at bertrand.benoit@wsj.com