Mercury, Venus, and Saturn put on an early-evening display in the west, while Jupiter dominates the rest of the night. Jupiter features many events involving its four major moons that are well worth chasing down. A remote annular eclipse of the Sun occurs on the 17th, visible only from Antarctica.

Mercury puts in a fine evening appearance during February. It reaches greatest eastern elongation 18° from the Sun on Feb. 19. With the high angle of the ecliptic to the western horizon after sunset, this places Mercury more favorably than at other times in the year. Watch the western sky as it darkens for the innermost planet.

Your first view might occur Feb. 10, when Mercury stands about 7° above the western horizon 30 minutes after sunset. At magnitude –1.1, it’s bright enough to punch through early-evening twilight. Some observers with a western horizon free of obstructions might also spot magnitude –3.9 Venus 1° high. Mercury sets shortly before 7 p.m. local time.

Mercury appears higher each subsequent evening as it climbs toward greatest elongation. On the 13th, it sets 80 minutes after the Sun. Grab some binoculars and see if you can spot the star Lambda (λ) Aquarii (magnitude 3.7) just 16′ from the planet. Magnitude 1.0 Saturn stands higher in the western sky and becomes visible as the sky darkens.

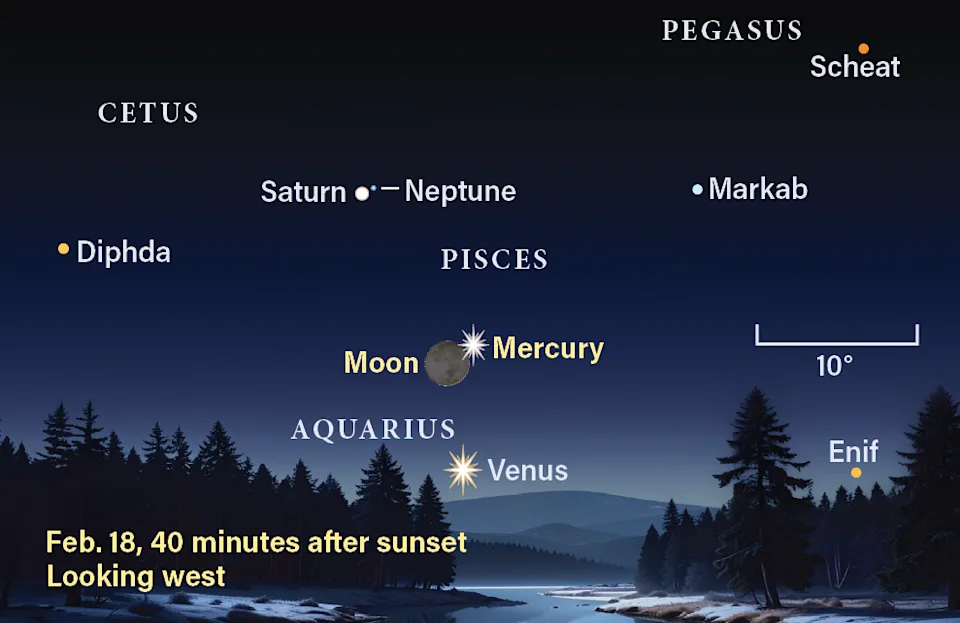

The western sky holds several planets after sunset midmonth. On Feb. 18, a thin crescent Moon joins in as well – some observers will see it occult Mercury. Note that Neptune is not visible to the naked eye. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

On Feb. 18, a 1.5-day-old crescent Moon joins Mercury in the western sky. Their relative positions change as twilight progresses across the U.S. East Coast observers see Mercury north of the Moon. By dusk on the West Coast, the Moon is almost 1° east of Mercury. Bright Venus hangs below them.

Lucky observers located along a narrow corridor of southern states (Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Georgia) will see Mercury disappear behind the Moon in an occultation. See http://lunar-occultations.com for local timing.

Later in the month, Mercury drops in elongation from the Sun as well as in magnitude as it heads toward an early March inferior conjunction. Meanwhile, Venus is rising higher. Feb. 23 finds the two planets 6° apart. Venus is 4° high 30 minutes after sunset and you’ll find Mercury, at magnitude 0, northeast of Venus.

Mercury stands less than 5° due north of Venus on the 26th; Mercury has now dimmed significantly to magnitude 0.8. Saturn is now 10° west of Mercury. On Feb. 28, Venus and Mercury stand side by side 4.8° apart, though Mercury is now magnitude 1.5. The pair sets an hour after the Sun. It will be hard to track Mercury after this date.

Saturn lingers in the western sky after dark. It resides in the constellation Pisces. Catch it early in February for good telescopic views. It stands about 30° high in the southwestern sky an hour after sunset on Feb. 1, shining at magnitude 1.0. By the 14th its altitude has dropped to 20° one hour after sunset. Telescopic observations become increasingly difficult later in the month due to atmospheric turbulence affecting the planet at low altitudes. By the end of February, Saturn stands only 7.5° high in the west an hour after sunset. It reaches conjunction with the Sun in late March.

Neptune lies within 1.8° of Saturn all month and becomes increasingly difficult to observe at lower altitudes as February progresses. Try so spot it in the first half of February. On Feb. 15, Neptune stands 0.9° due north of Saturn, within the same low-power field of view in many telescopes. It shines at magnitude 7.8, easily within range of binoculars.

Uranus returns to easterly motion after the 3rd, starting February 5° south-southwest of the Pleiades (M45). On Feb. 1, Uranus stands 0.7° southwest of the 6th-magnitude star 13 Tauri. Any motion back toward this star isn’t noticeable until the second week of the month. A waxing Moon passes across the northern limits of M45 on the 23rd, when Uranus lies 0.6° from 13 Tau. The planet draws to within 0.5° of the star by the 28th.

By 7:30 p.m. CST on Feb. 23, the Moon is preparing to pass in front of a portion of the Pleiades. Uranus – which will require optical aid – is also in Taurus. You will need magnification to spot Neptune, near Saturn, as well. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Through a telescope, Uranus reveals a pale greenish disk spanning 4″. Observers with experience in high-speed video capture of planets might want the challenge of recording Uranus while it is high in the sky soon after sunset.

Jupiter is visible all night after passing through opposition last month. It starts the month at magnitude –2.7 among the stars of Gemini the Twins.

Jupiter’s disk – 46″ wide as the month opens – offers a lot of detail in telescopes of almost any size. Two dark belts straddling the equator are most obvious. Look for subtle features along their edges, such as dark material encroaching into the adjacent white zones. The planet rotates quickly, with the equatorial regions completing one rotation in nine hours and 50 minutes, and higher latitudes taking five minutes longer.

Occasionally you’ll see the Great Red Spot along the southern edge of the South Equatorial Belt. If it’s not visible when you look in the evening, try again a few hours later. It’s bound to come into view sooner or later.

Jupiter’s four largest moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – dance around the planet in ever-changing positions with periods ranging from two to nearly 17 days. February offers a full series of transits, occultations, and shadow transits. These events are an exercise in visualizing orbital motion: Inner moons move faster than outer ones, and resonant orbits produce repeating events.

With Jupiter now past opposition, during satellite and shadow transits the moon transits first, followed by its shadow. By now, the gap between these events is wider than in January.

The first evening of February hosts a transit of Europa. Europa begins to transit at 7:37 p.m. EST, followed by its shadow at 8:42 p.m. EST. Similar events occur on Feb. 8 and 15/16, at progressively later times in the evening. On the 8th, Europa’s transit begins at 9:54 p.m. EST, then at 12:15 a.m. EST on the 16th (in the Eastern time zone only, still the 15th farther west). Its shadow follows 83 and 99 minutes later, respectively, on these nights.

Callisto disappears behind the northwestern limb of Jupiter Feb. 3 at 9:34 p.m. EST. One and a half orbital revolutions later, on Feb. 28, Callisto begins a transit in front of Jupiter around 10:20 p.m. EST.

Io orbits Jupiter every 42.5 hours and produces many events. On the 4th, Io begins a transit at 10:20 p.m. EST, followed by its shadow 35 minutes later. Note that the separation between transits of Io and its shadow is smaller than for Europa. Why? Europa is in a larger orbit, so lies farther from Jupiter.

Io transits again Feb. 11/12 at 12:06 a.m. EST (the 12th in EST only), and again Feb. 18/19 beginning at 1:54 a.m. EST on the 19th.

Ganymede is the largest moon and thus casts the largest shadow on Jupiter. U.S. East Coast observers will see Ganymede’s shadow on Jupiter as darkness falls on Feb. 11.

Shortly after 9 p.m. EST on Feb. 18, Ganymede has completed a transit and its shadow has appeared on Jupiter’s cloud tops for a transit of its own. Callisto is to the west, while Io and Europa lie to Jupiter’s east, outside this field of view. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

On the evening of Feb. 18, East Coast viewers see a transit underway as soon as it’s dark. Ganymede takes just over three hours to cross the disk of Jupiter. It leaves the disk by 5:44 p.m. PST, roughly sunset on the West Coast. But there’s more to come – the giant shadow begins a transit some 10 minutes after the moon clears the disk. Watch the southeastern limb for the black notch beginning to grow. A few minutes after 9 p.m. EST, the shadow is fully on Jupiter’s disk and it, too, takes a bit more than three hours to cross.

Ganymede repeats its transit on the 25th at 8:55 p.m. EST, and its shadow appears exactly four hours later.

You can see Ganymede disappear behind Jupiter’s northwest limb earlier in February. Look on the evening of Feb. 7/8 starting at 12:02 a.m. EST, as the giant moon is gradually hidden behind the planet. This event is visible across the continental U.S.

Mars is just past its superior conjunction with the Sun and isn’t visible this month.

There’s an annular eclipse of the Sun Feb. 17 with limited viewing. The track crosses a portion of Antarctica’s icy expanse. A small partial eclipse is visible from southern Africa and Madagascar. An annular eclipse occurs when the Moon is near apogee and doesn’t quite cover the Sun at maximum eclipse, leaving a brilliant ring of sunlight, called an annulus – hence the name of this type of eclipse.

Note: Moon phases in the calendar vary in size due to the distance from Earth and are shown at 0h Universal Time. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Rising Moon: Terrific trio

Lunar craters Theophilus, Cyrillus, Catharina

It’s a smorgasbord of fantastic views on the crescent Moon as it grows from the slenderest of arcs to a half-illuminated disk. The terminator zone straddling day and night is chock-full of rolling seas bordered by craters with towering peaks and aprons of debris. On Feb. 22, our focus is to the south, but never throw away a chance to first enjoy the Serpentine Ridge snaking across the large Sea of Serenity in the north.

Immediately south of the lunar equator, a terrific trio of craters grabs the eye. Theophilus is the most classic of the three: Its rim is sharp, almost perfectly circular, and sports a dramatic multiple central peak. Because it is much bigger and deeper than smaller Mädler immediately to the east, the walls of Theophilus slumped into terraces that are most noticeable on the western flank.

You can make some pretty good guesses at the relative age of a feature without needing the sharper tools of a lunar geologist. Theophilus must be the youngest because it overlays the ragged rim of the crater to the southwest. Cyrillus too has a complex peak and slumped walls, but they are degraded from the impacts of smaller objects as it aged. Plopped all around Theophilus in an apron, the impact ejecta partially fills neighboring Cyrillus. The rough texture is really obvious at this phase. Under a high Sun at Full Moon, this topographic detail vanishes, leaving just the ring of the rim for identification. Mädler seems to shelter the terrain to the east from the debris, hinting at an intermediate age.

The southernmost of the trio is Catharina, undoubtedly once sharp-featured like Theophilus, but millions of years of bombardment have erased the central peak and left its walls softer and lower.

Return to observe March 23 when the Sun is lower in the lunar sky, producing longer shadows that exaggerate the apparent heights. To the trio’s southeast in the Sea of Nectar is a wrinkle ridge that formed when the lunar crust was slowly compressing, leaving the ground nowhere to go but buckle upward, just like the Serpentine Ridge north of the equator.

Meteor Watch: Sky lights

Major meteor showers skip February altogether. Random or sporadic meteors from ancient streams long since dispersed produce about a half-dozen meteors per hour. Meteors are always best seen after midnight under a dark, moonless sky. In the runup to dawn, you’re sitting on Earth’s leading hemisphere as it orbits the Sun, resulting in higher velocities as any cometary detritus enters the atmosphere.

Also visible on moonless evenings in February is the zodiacal light. This dim glow, aligned with the ecliptic, extends steeply above the western horizon well after the low arc of the twilight glow has diminished. From completely dark locations, the zodiacal light is almost as bright as the Milky Way. The cone extends upward through Aquarius, Pisces, and Aries. A line connecting Mercury and Saturn shows the way.

Scan your eyes left and right and your peripheral vision will pick up the cone-shaped glow. The middle of the month, starting after Feb. 6, is the best time to look, with the bright Moon out of the evening sky.

The soft glow of the zodiacal light appears over Georgia’s Lake Tobesofkee in early 2016. Credit: Stephen Rahn

Comet Search: Lower latitudes lead

The VIP comet this month is 6th-magnitude C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś). After a nice showing in the south, this month it fades gracefully for northern observers, last to the viewing party. Visible to the unaided eye south of the equator from a dark site, the comet pales into binocular range by the second week of February for the Gulf States. It’s midmonth by the time it climbs high enough to be seen in deep evening twilight from the Great Lakes.

Do your best to ignore the waxing Moon and go to medium power to uncover details. Having just passed its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) Jan. 20 and now halfway between the orbits of Mercury and Venus, the core will be active. Because the shroud of expelled dust hides the comet’s surface, the bright spot we see is called the false nucleus.

Compare Wierzchoś to 24P/Schaumasse, last month’s featured comet, located in the morning sky. In contrast to Schaumasse’s round inner core, Wierzchoś will be decidedly ungalaxylike. The east and north flanks will be sharp where the solar wind blows away the gas and dust tails. The softer glow of the tilted fan fades into the west.

This chart shows the path of Comet Wierzchoś in the second half of February. Only deep-sky objects brighter than 10th magnitude are shown. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Locating Asteroids: A reasonable choice

When an object reaches opposition, Earth takes the middle seat between the Sun and our target, forming a nearly straight line. Just past its opposition last month, asteroid 44 Nysa is still reflecting the most light possible, peaking at 9th magnitude this month. It is highest at midnight – somewhat inconvenient for early-evening stargazers – but it’s easy to locate, just two finder fields from Pollux if you head away from Castor. You’ll find it just south of 5th-magnitude Mu2 (μ2) Cancri.

Nysa is a modest dot from the suburbs in a 3-inch scope, yet easier than neighboring field stars on the 1st. By the 6th it lies close to one of two brighter field stars. From the 11th through the 13th, Nysa slides through an extended quad of stars, then enters a notably different array for the last week of the month. Any of these mini-encounters is perfect for sketching its night-to-night displacement.

It took almost 50 years from Giuseppe Piazzi’s 1801 discovery of 1 Ceres rack up 20 known asteroids. German astronomer Hermann Goldschmidt found 21 Lutetia in 1852 and Nysa in 1857, two in a prodigious haul of 13 in less than 10 years. He meticulously updated star charts and noted any changes, also discovering variable stars along the way.

Nysa tracks past several field stars in Cancer and Gemini this month, located near Mu^2 Cancri (labeled simply μ in the chart above). Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. February 1

9 p.m. February 15

8 p.m. February 28

Planets are shown at midmonth

The post February 2026: What’s in the sky this month? Jupiter continues to dominate the night; Mercury, Venus, and Saturn are visible appeared first on Astronomy Magazine.