On a recent sunny afternoon at Cal Anderson Park on Capitol Hill, a Rolodex of looks streamed past: a leather jacket paired with a furry-flapped hat, baggy jeans with fall-ready boots, and lots of black layers. The occasion? The inaugural 206 Fresh Fits Competition, where social media creators Mavin Wilkes and Jadan Reynolds invited their followers to show up, strike a pose and win bragging rights. It was an algorithmic open call that felt distinctly Seattle: egalitarian and slightly irreverent. It was an interesting entry point to a bigger question that’s been simmering lately: What is Seattle fashion — right now?

The short answer: It’s a city dressing on two tracks at once. One track prizes function and the outdoors — workwear, flannel, trail-ready textiles, the sneaker as a north star. The other insists on cosmopolitan connection — boutiques, couture houses, gallery openings, and the kinds of looks that speak to a global fashion ecosystem. These threads have tugged back and forth for more than a century.

Early department stores in Seattle, such as MacDougall & Southwick in the late 1800s, weren’t only purveyors of clothing; they were agents of modernity, wiring in telephones, switching on electric lights, and, famously, installing one of the first elevators in Seattle. They even dispatched buyers to Europe in the early 1900s, indicating that the city wanted a seat at fashion’s larger table.

Best’s Apparel, co-founded downtown in 1925 by Dorothy Cabot Best, became the refined counterpoint — tasteful, curated, and eventually important enough to be acquired by an ascendant Nordstrom in the 1960s, when the local shoe merchant had ambitions well beyond footwear. A generation later, the city’s retail guard would canonize names like John Doyle Bishop — part buyer, part tastemaker — whose New York and Paris jaunts connected Seattleites to what was happening elsewhere, while Helen Igoe’s high-fashion shop modeled how a West Coast city could traffic in continental chic.

And yet, Seattle has always insisted on its own uniform. Our climate is a stylist with strong opinions, and our topography a standing invitation to step outside. That practicality morphed into bona fide influence: the down-filled jacket popularized by Seattle outfitter Eddie Bauer (patented in 1940) codified the idea that technical warmth could look intentional. Designers have been mining that vein ever since.

If the city once toggled between mountain and metropolis, today’s Seattle answers: yes, and. Over the last year, on First Thursdays in Pioneer Square — the nation’s longest-running art walk — the looks have become as much an attraction as the art. Galleries stay open late, retail doors roll up and street style-forward looks arrive in droves to Occidental Square.

New players are powering that ecosystem. Vintage entrepreneur Erika Vazquez, owner of the boutique FRIDA in Pioneer Square, built a following long before her brick-and-mortar opened on First Avenue South, then doubled down on experience: cobalt-blue fixtures, florals, late hours and a team schooled in hospitality. “Style is the first nonverbal language when you walk in a room,” she explains. In her telling, Pioneer Square’s art walk works because it’s welcoming and because Seattle is finally saying out loud that clothes are art, too.

Institutionally, there’s legacy, and a living one. Luly Yang turned a paper butterfly gown into a couture house and a design group that now spans bridal, eveningwear and uniforms, remaking the city’s perception of what “Seattle designer” can mean. On the emerging front, names like SSKEIN are recoding knitwear with a Pacific Northwest tactility — soft power dressing in merino and alpaca, engineered for modern life. Designers such as Angeline Brunk and Lisa Marie Ottele add to the mix, proof that made-here doesn’t have to mean muted-here.

Museum voices offer a useful lens for why this feels catalytic. The Museum of History & Industry’s Clara Berg sketches a through-line: Seattle has long harbored an anxiety about being far from fashion centers, and clothing has been one way we show that we’re connected — to culture, to industry, to the broader conversation. Historically, department stores and independent boutiques functioned as literal connectors, sending buyers across oceans and bringing back newness. Today, creators and curators do the same thing using social networks and smartphones. The mechanism has changed; the impulse hasn’t.

Still, the story isn’t only about supply chains and store names. It’s about how — and where — Seattleites dress now.

“A lot of people in the Northwest have really active lives, so the gravitation toward athleisure and ‘active’ has become predominant,” says Terri Morgan, fashion show producer and owner of TCM Models & Talent. “We have a good fashion market, it’s just that people don’t tend to dress up on a daily basis. Fashion in general has taken on a more relaxed tone.” In other words: Where another city might reach for stilettos, Seattle edits the same look with a kitten heel, a lug-sole boot, or a tennis shoe — function as a finish, not an afterthought.

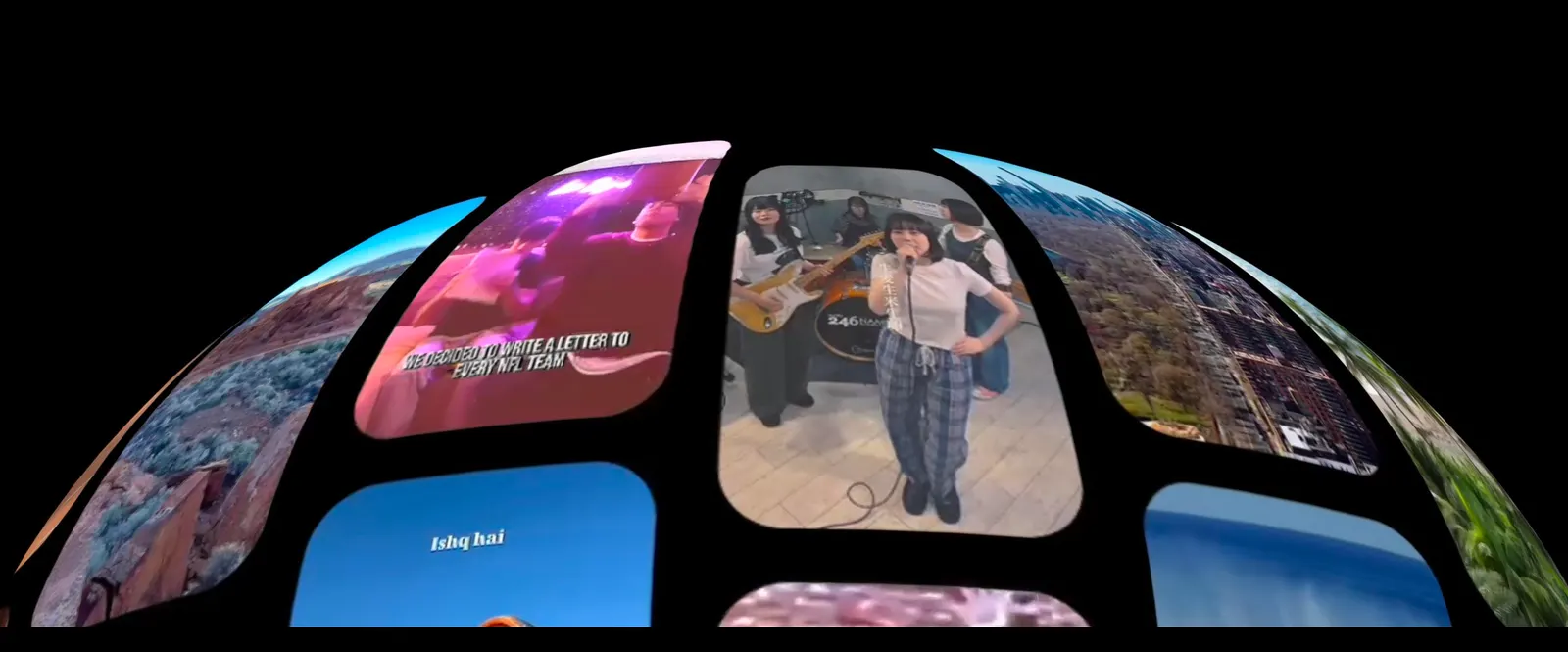

Which brings us back to the park. The 206 Fresh Fits afternoon had the same generosity as the Pioneer Square Art Walk: nobody waiting for a velvet rope, everybody eager to see and be seen. The winning looks didn’t fit into a specific genre; they were a stance — intentional, whether expressed in a plaid kilt paired with a leather jacket or a leather jacket with wide-legged denim. If there’s a single definition for Seattle fashion right now, it’s this: style as individual expression.

That idea surfaced again and again in conversation. Retailers talk about service like theater — scent, sound, pacing — because experience is now as important as the garment. Designers speak in materials: cashmere as cloud cover, knits that hold shape against the rain and suiting that transitions from a board meeting to a happy hour. Vintage is no longer nostalgia; it’s sustainability. And everywhere, there’s a willingness to mix: high with low, local with global, rain shell with satin.

To be clear, Seattle didn’t just wake up fashionable. The proof is in the record: early department stores connecting this “outpost” to Paris and New York; women merchants and tastemakers carving space for themselves in a male-dominated business; later, homegrown retailers scaling into national players. The old anxiety — are we a “real” city if we don’t dress like one? — feels dated now, replaced by a new question: What can our particular climate and culture teach fashion? The answer might be as simple as our fair city’s forecast: adaptability, layered with intention.

Back at Cal Anderson, the 206 Fresh Fits crowd cheered a winner, but that seemed beside the point. The real prize was the picture that lingered: a city of dressers meeting to compare notes, pose for the cameras, and, for a few hours, make a park feel like a page in a magazine. That, more than any taxonomy, is Seattle fashion now: community-made, climate-literate, globally curious and increasingly unafraid to be seen.