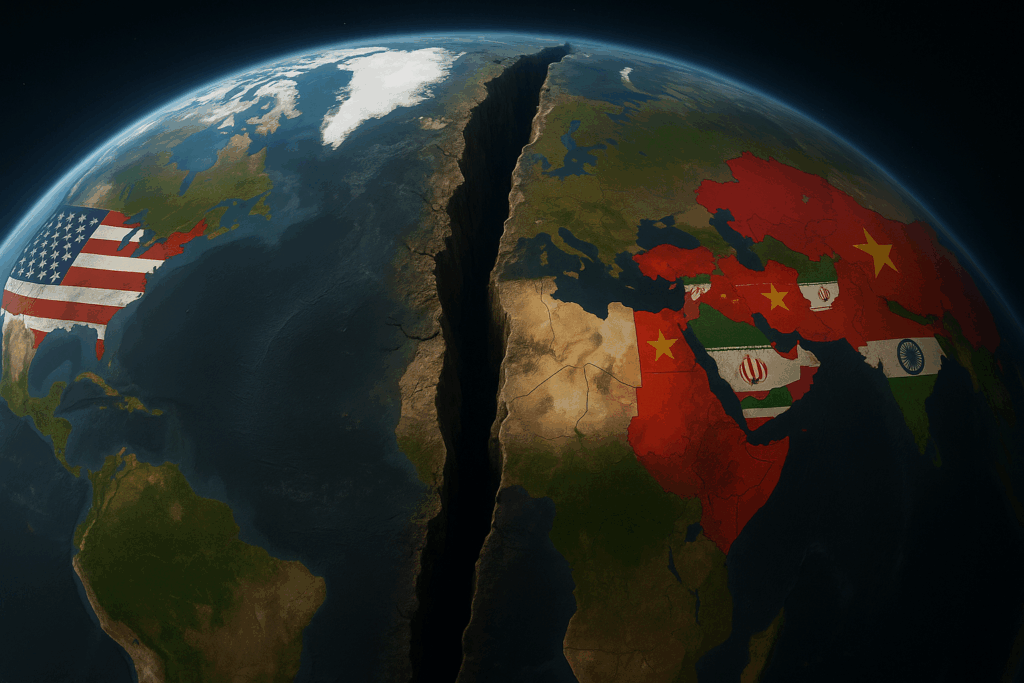

The world today is more unsettled and volatile than ever. The war in Ukraine has become Europe’s largest conflict since World War II. Tensions between Israel and Iran cast a heavy shadow over the Middle East. Taiwan issues spark new threats almost daily. The gap between Europe and the United States is becoming increasingly evident. Trade wars between East and West are turning into a fierce and decisive struggle.

In this complex environment, world leaders are facing sanctions, isolation, and strategic setbacks that send a clear message—the long peace may soon end. Whether China’s supreme leader, Xi Jinping, will play a positive or divisive role in the future is uncertain.

It is certain that China seeks to move from the role of “model student” to that of leader, all despite depending heavily on Western markets and technology. The United States and the European Union remain China’s largest trading partners and any disruption in these relationships could push its economy toward stagnation. How China’s ambitious transition addresses major paradoxes and limitations in three key areas deserves further discussion.

The Alliance Paradox

At first glance, dissatisfied countries may appear a united front against the West, with China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and, to some extent, India in alignment. A closer look shows deep-rooted tensions. Russia inherited the legacy of empire and finds it difficult to accept a subordinate role to China. While Moscow relies on Beijing’s support in Ukraine, China’s growing economic and security influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus is seen as a direct threat.

India, another key player, sits with China in forums like BRICS, but remains a strategic rival. Border disputes in the Himalayas, competition for influence in the Indian Ocean, and strong ties with the United States and the West prevent any real constructive partnership between the two Asian powers.

Iran and North Korea also face serious internal and international constraints. Iran struggles with deep domestic cleavages, while North Korea remains unpredictable, at times even complicating China’s strategic plans. On a broader level, there is no shared set of values among these countries; their primary connection is opposition to the West.

As Henry Kissinger noted, such alliances often reflect disorder rather than creating a new order. This coalition is more capable of disrupting the existing system than building a replacement. None of its members, individually or collectively, possesses the institutions or tools required to reshape global order.

Xi Jinping’s presence alongside this coalition primarily serves as a symbolic display, signaling dissatisfaction, demonstrating power, and marking the end of a unipolar world. But this performance does not equate to practical ability to establish a new order. While China wields significant economic power, it lacks the instruments to replace the West in security and international politics; it has no NATO-like network, no universally trusted currency, and no capacity to reshape international legal institutions to its advantage.

The Contradiction between Experience and Ambition

One of China’s main challenges is its lack of practical experience in major global tests. Since World War I, China has not been involved in any large-scale wars and has not faced a real-world military crisis. This gap highlights China’s inexperience in handling major international conflicts. Even considering Russia, with its weakened military and struggling economy, and Iran, facing deep domestic and regional crises, the pillars of this alliance do not appear particularly strong.

Ambition without experience, combined with an alliance lacking shared values, risks creating instability rather than a new order. This coalition sends an important message to the West, especially the United States: global dissatisfaction with American hegemony is real and even temporary alliances can exert significant pressure on energy markets, financial systems, and peace negotiations. China and its partners, despite their fundamental weaknesses, can disrupt Western calculations across many regions—a capability that should not be underestimated.

At the same time, China’s lack of hands-on experience in managing major military and economic crises leaves its foreign policy vulnerable to miscalculation. Ambition without real-world testing can thus be both an opportunity and a threat to regional and global stability. Moreover, global leadership is not possible by economic or military power alone; it also requires a compelling culture and a large consumer base capable of attracting goods, technology, and lifestyles from other countries. The United States built its hegemony precisely on these foundations. China possesses none of these.

Message to the World and the West

Xi Jinping’s alignment with countries opposing the existing global order sends a dual message to the world. First, it signals widespread dissatisfaction with the current system. This shows the world, particularly the West, that the liberal international order is no longer uncontested and that the hegemony of the United States faces a challenge. Second, it exposes the weaknesses and contradictions within the anti-Western coalition. The alliance lacks the intellectual, institutional, and operational foundations needed to create a new order. Internal divisions and the absence of security and political tools indicate that China and its partners, at least in the short term, cannot replace the existing global order.

Nevertheless, China’s stance against the liberal international order marks a new phase in global politics—one that may not produce a new order but could intensify instability and geopolitical complexity. Henry Kissinger even considered such disorder a threat greater than war. This situation shows that China is simultaneously trying to display power, secure advantages, and strengthen its global position, yet it still faces significant constraints and challenges on the path to genuine global leadership.

Conclusion

China’s transition from the “model student” to “global leader” faces three key obstacles. First is the alliance paradox in which coalitions of dissatisfied countries reflect disorder more than they create new order. Second is the gap between experience and ambition in which ambition without major practical tests leaves China vulnerable and its foreign policy prone to miscalculations. Third is the alliance/coalition’s message to the world, where China loudly signals its dissatisfaction with the current order but has no attractive alternative to offer. In other words, China seeks a larger share of the global order, yet it lacks the capacity to host it.

Today, the world is entering a new phase—one that may not produce a new order but will likely heighten instability and geopolitical complexity. In this environment, conflict remains the most probable scenario.

Dawood Tanin is a researcher, freelance writer, and professor of political science at a private university in Afghanistan. Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.