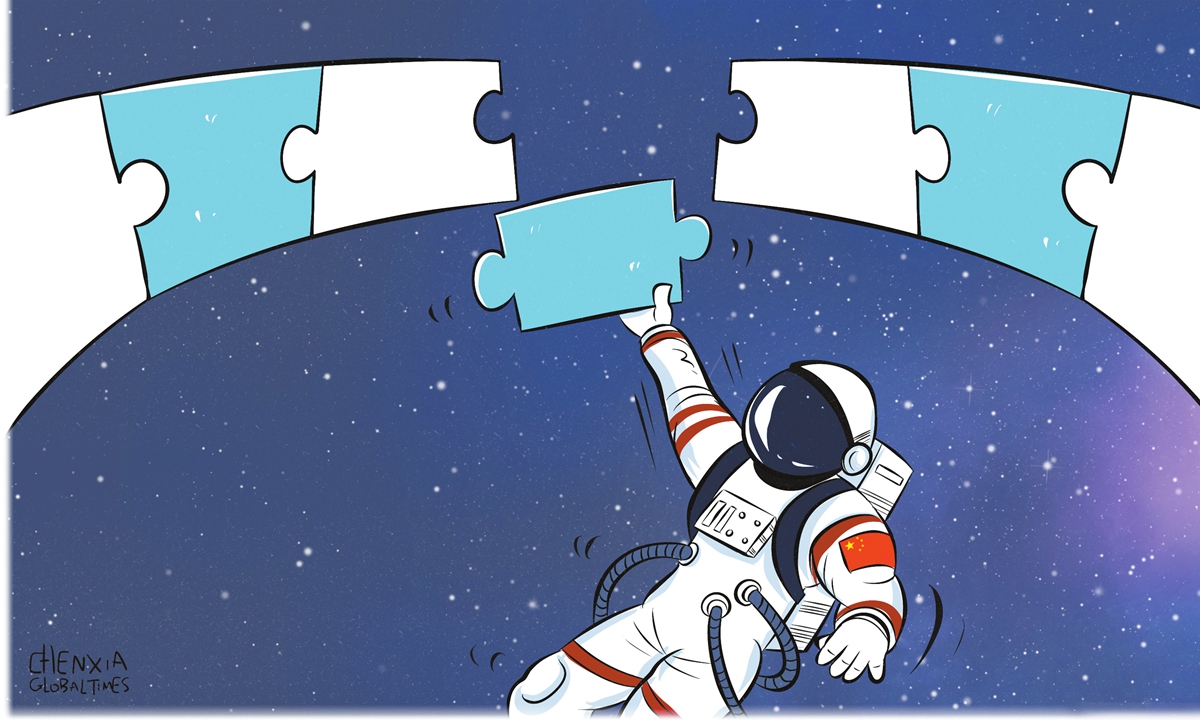

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

The recent decision by China’s space agency to grant NASA-funded American universities access to lunar samples – retrieved from the moon’s far side – offers more than a scientific opportunity; It is a poignant reflection of two fundamentally divergent approaches to technological advancement.

These different approaches shape the trajectory of space exploration and reveal broader truths about global technological competition, the limits of isolation, and the path China-US cooperation should take.

US’ space program is built on free-market dynamism and decentralized innovation. The ecosystem thrives on the interplay between government entities like NASA and a robust private sector, exemplified by companies such as SpaceX. Ideas flow freely between top-tier universities, research labs, and entrepreneurial ventures, with venture capital fueling risky innovation.

Yet, regarding safeguarding core technological advantages, Washington erects formidable legal and regulatory barriers. For example, the Wolf Amendment (2011) forbids NASA from bilateral cooperation with Chinese agencies, underscoring America’s intent to protect strategic technologies.

China, by contrast, embraces a centralizing model, leveraging the sheer organizational force of the state. Under a unified national directive, it marshals vast resources and talent from public research institutions, state-owned enterprises, and an expanding private sector to achieve breakthroughs – despite, and sometimes because of external constraints.

Confronted with technical embargoes, China responds not with acquiescence but intensified investment and accelerated innovation. Simultaneously, Beijing has positioned itself as a willing partner, inviting collaboration and sharing lunar samples with scientists from around the world – even those from countries whose governments actively limit cooperation with China.

The essence here is clear: The US counts on encouraging innovation from many different sources, while at the same time carefully keeping out certain competitors. In contrast, China invests in system-wide, strategic mobilization coupled with an increasingly outward-facing posture.

Each philosophy represents both a competitive wager and a vision of what the future of technological leadership should look like.

When US lawmakers imposed the Wolf Amendment in 2011, they sought to slow – if not outright block – China’s ascent in space technology. The logic was Cold War-tinged: deny access, maintain US primacy, and keep potential adversaries in check. Yet more than a decade later, this strategy has yielded diminishing returns.

Exclusion has had the unintended effect of galvanizing China’s capacity for self-reliance. Where collaboration was blocked, Chinese labs doubled down on domestic research, often achieving results that American policymakers believed would be out of reach.

China is now the third country in history to return samples from the moon, and the first to deliver material from its far side – an accomplishment forged in the shadow of US’ restrictions.

China’s comprehensive industrial base and vast reserve of scientific talent confer a resilience that makes technological stalling by embargo nearly impossible. The Chinese system does not depend on a single external supplier or educational pipeline, allowing for parallel investments and redundancies that offset losses in international collaboration.

In sum, the American approach – to isolate and contain – has not stopped China’s progress but inadvertently spurred it.

If US’ technological policy is, at root, an attempt to cement its global preeminence through a zero-sum calculus – where one nation’s gain is another’s loss – the logic falters under the weight of 21st-century interdependence.

Great scientific leaps have always come from collaboration across borders, not rigid exclusion.

Clinging to strict technological protectionism will backfire. It risks driving innovation redundantly – forcing nations to reinvent wheels that could have been shared – and isolates American researchers from scientific developments elsewhere. As the global order shifts and more countries reach the technological frontier, constructing a wall around American science becomes costlier and less effective.

Moreover, humanity’s grand challenges – climate change, space exploration, pandemics – are inherently transnational. A narrowly defined race for supremacy turns the world’s brightest minds away from pressing common problems in favor of abstract contests for dominance.

What, then, should the future look like?

China’s gesture of lending lunar samples to US-based (and NASA-funded) university research teams is not trivial; It is a statement of principle and intent. Rather than reciprocating exclusion with exclusion, China signals a willingness to subordinate political grievance to scientific advancement.

As described in recent reports, Chinese officials have made it clear: Erstwhile US openness has curdled into defensive insularity, even as China becomes more confident in sharing the fruits of its endeavor.

The lesson of the lunar samples is clear: In this new age of possibility, it is not walls but bridges that will define true leadership.