New Delhi: Nepal’s Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli walked a diplomatic tightrope, navigated geopolitical tension, addressed several constituencies – internal and external – and flew out of Beijing with a satisfactory deal after his December 2-5 visit to China. After weeks of speculations, Nepal and China had signed the Framework for Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Cooperation, leaving room for case-by-case negotiations, instead of agreeing to a blanket BRI implementation plan.

Though a small step, the blueprint could set a larger template on how Nepal balances its small-state anxieties, takes Beijing into confidence without alienating Delhi and Washington (and vice versa), and also manages to navigate deeply fractious domestic politics. It’s never easy for any government in Kathmandu to strike a fine balance between domestic economic imperatives and the geopolitical tension. Nepal’s foreign minister Arzu Rana Deuba is likely to visit New Delhi on December 19 and her team is expected to propose mid-January as a possible date for Oli’s visit to Delhi.

Despite the constraints he faced, Oli’s visit had enough for both Beijing and Kathmandu to appreciate. As importantly, the 12-point joint statement has much to build on – a quiet recognition that the bilateral ties are very important for both, but a lot remains to be done.

Nepal’s communist parties have historically enjoyed close political relations with Beijing but Oli avoided signing a bilateral deal that would come back to bite him politically. The BRI Framework agreement instead was prepared by a four-member joint task force with representatives from both the PM’s CPN-UML (the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist) and the centrist Nepali Congress, the largest party in the ruling coalition.

Geopolitical balance

Here’s the readout.The Nepali side reiterated that “Xizang affairs are internal affairs of China,” and that it will never allow any separatist activities against China on Nepal’s soil. The joint statement notably uses the term Xizang instead of Tibet, as is the Chinese political practice in recent times. Equally notable is the fact that Nepal also “firmly supports China’s efforts to achieve its national reunification and opposes “Taiwan independence.” Chinese opposition to “Taiwan independence” in joint statements is a much recent phenomenon. Also, the two sides appreciated the initiations taken to implement the MoU on translation and publication of classics – a growing emphasis on deepening cultural partnerships.

The most notable – and potentially also the most volatile – feature has been cleverly worded: “The two sides agreed to strengthen the synergy of their development strategies and pursue deeper and even more concrete high-quality Belt and Road cooperation.” It has avoided tethering Kathmandu to any terms on BRI agreements. By all means, the terms for any BRI project will be negotiated on case-by-case basis.

The two sides agreed to expedite the development of 10 projects but will have to finalise project-specific agreements. They have expressed commitment to strengthening connectivity in such areas as ports, roads, railways, aviation, power grids and telecommunication “to help Nepal transform from a land-locked country to a land-linked country.”

Here are some concrete project proposals: advance the China-aided Araniko Highway maintenance project and the Hilsa-Simikot Road project – both important border crossings connecting Tibet with Nepal. In Kathmandu, works on the second phase of the much-delayed Ring Road Improvement Project and feasibility study on the Tokha-Chhahare Tunnel will start.

Also Read: Meet KP Sharma Oli who is set to become Nepal’s new prime minister

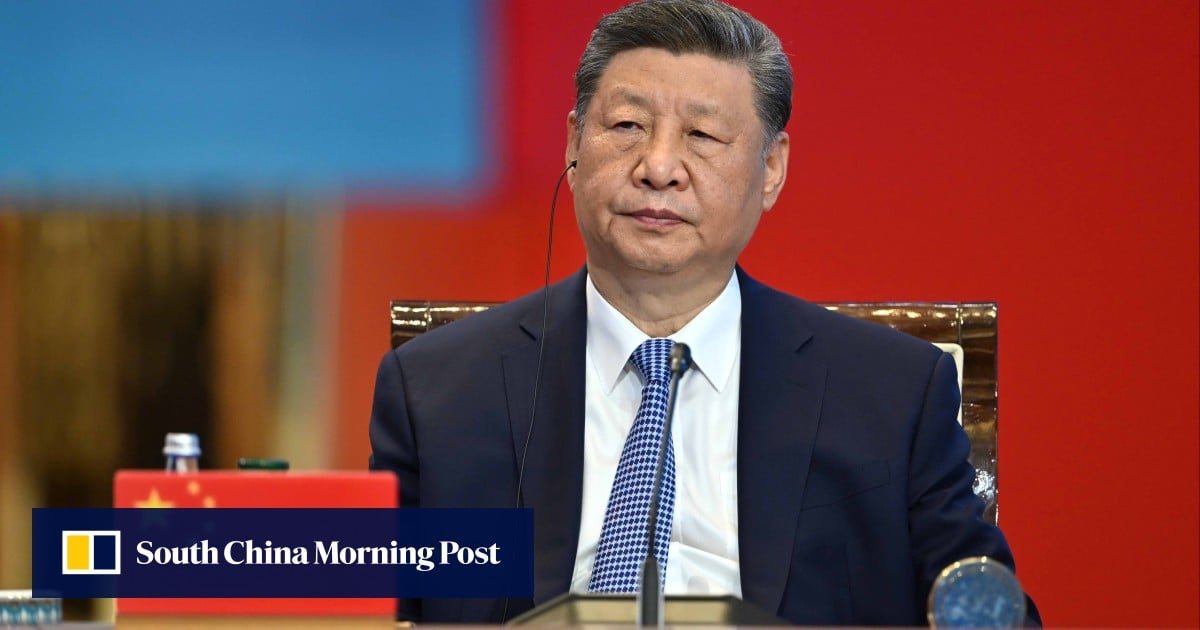

The two sides also agreed to expedite works on three important North-South economic corridors, following on the commitment made during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Nepal in 2019 – Koshi Economic Corridor in eastern Nepal, Gandaki Economic Corridor in western Nepal and Karnali Economic Corridor in far western Nepal.

After years of closure due to Beijing’s zero-Covid policy, the two sides noted “full resumption” of 14 traditional border trade points that have been pivotal in promoting both bilateral trade and making the livelihood of residents on either side of the border easier. Nepal has requested China to consider the possibility of opening more bilateral and international ports. The Chinese side will facilitate the construction of the China-aided Inland Clearance Depot (ICD) and Integrated Check Post (ICP) at Korala in Mustang. Korala is expected to be the most important border crossing with China in Nepal after Tatopani and Kerung, both of which are close to Kathmandu and gateway to central Nepal.

The two sides also agreed, fittingly, to “value the development of civil aviation ties,” and open flights between Chinese and Nepali cities such as Pokhara and Lumbini in light of market demand, so as to facilitate bilateral economic and trade ties and two-way travel. This is important because both Pokhara (built on a Chinese loan) and Lumbini airports have struggled to get international flights, turning them into white elephants. However, the joint statement is notably silent about Nepal’s long-standing request to China to convert a China Exim Bank loan (Rs25.88 billion) that went into the construction of Pokhara International Airport to a grant.

Nepal has voiced its support for the Global Development Initiative (GDI) proposed by China but has avoided being part of its Global Security Initiative (GSI), an international security order launched in April 2022, promoting a set of security concepts and principles reflecting Beijing’s international normative preferences.

The stakes of the visit were high as Oli had made a significant political departure: His first port of call after taking office in July was Beijing, not Delhi. Additionally, the largest party in the ruling coalition, the Nepali Congress, had openly voiced its reservations about accepting loans from China under the BRI framework, Xi’s flagship foreign-policy architecture. Though Nepal signed the BRI agreement in 2017, there has been very little progress on its project implementation.

Former PM Sher Bahadur Deuba, who is also the president of the Nepali Congress, has unambiguously conveyed to the visiting Chinese leaders that Nepal is in no position to finance BRI projects through loans. In 2022, the then government of Deuba had emphasised three terms on BRI financing: first, Nepal prefers grants over loans; second, in case of loans, the interest rate should not exceed one percent and the terms for repayment on the concessional loan should be similar to those of the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and other multilateral lenders; third, there must be a competitive bidding process. In recent years, Nepali Congress’ stance on BRI has largely been the dominant position across the political spectrum.

On the eve of Oli’s visit, both he and Deuba were well aware that they couldn’t be seen to be reneging on promises that had been made in the past. It could prove particularly costly for the Congress.

Nepal’s Communist parties on the other hand have enjoyed cordial ties with the Communist Party of China and Beijing, best evidenced in their regular party-to-party exchanges, regardless of whether Oli’s party, CPN-UML (the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist, or the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center) headed by Pushpa Kamal Dahal, also a former prime minister, is in office.

Nepali stakeholders, including those outside the political parties, welcome stronger ties with Beijing, but would be deeply wary of Nepal turning into a space of geopolitical competition. From Nepal’s perspective, the political rationale for engagement with China is simple: it helps balance ties with Delhi, the U.S. and the West, and the world’s second-largest economy has the economic heft to provide concessional loans and grants, alongside cheap technology to build Nepal’s infrastructure.

Joint taskforce a masterstroke

The NC-UML taskforce was a win-win formula not only for the ruling parties. In the much-contested internal political theatre in Nepal, Beijing also wanted to see an agreement that was backed by broader consensus. Congress was represented by general secretary Gagan Thapa and advocate Semanta Dahal, who has international experience on infrastructure financing and BRI negotiations. UML was represented by Oli’s two close aides – Bishnu Rimal, his political advisor, and Yubaraj Khatiwada, his economic advisor. The task force comprehensively reviewed the BRI implementation plan proposed by China as early as 2020 in view of the differences between the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML on the BRI implementation plan, with Nepali Congress in particular suggesting that Nepal should avoid loan-based BRI projects.

When Arzu Rana Deuba and Oli (possibly soon) visit Delhi next, the balancing act and all the groundwork that went into finalising the joint statement in Beijing could offer a handy foreign-policy guideline for Nepal.