A decade ago, in the remote highlands of Kashmir, I experienced a minor cultural revelation: a parcel from Amazon, bearing books unavailable in Srinagar’s bustling city markets, arrived at my doorstep. This moment crystallised my early reverence for Jeff Bezos – then a mere name to me – whose venture had begun, as a friend reminded me, as a humble online bookstore. In that instant, Amazon seemed a noble democratisation of knowledge, a triumph of nascent computer science bridging geographical and cultural chasms. Walter Benjamin’s lament for the “aura” of the original artwork felt momentarily countered by this new accessibility; technology appeared to expand cultural horizons rather than diminish them. Yet, this admiration proved fleeting. Within a few years, Amazon metastasised into a global commercial leviathan. By 2015, its annual revenue surged past $100 billion, and Bezos ascended relentlessly, his name perpetually etched among the planet’s top oligarchs. His trajectory embodied what economist Thorstein Veblen presciently termed “conspicuous production” – the relentless, often predatory, scaling of enterprise not merely for profit, but as a performative display of industrial dominance. The noble bibliophile’s endeavour had irrevocably mutated into an engine of unprecedented accumulation.

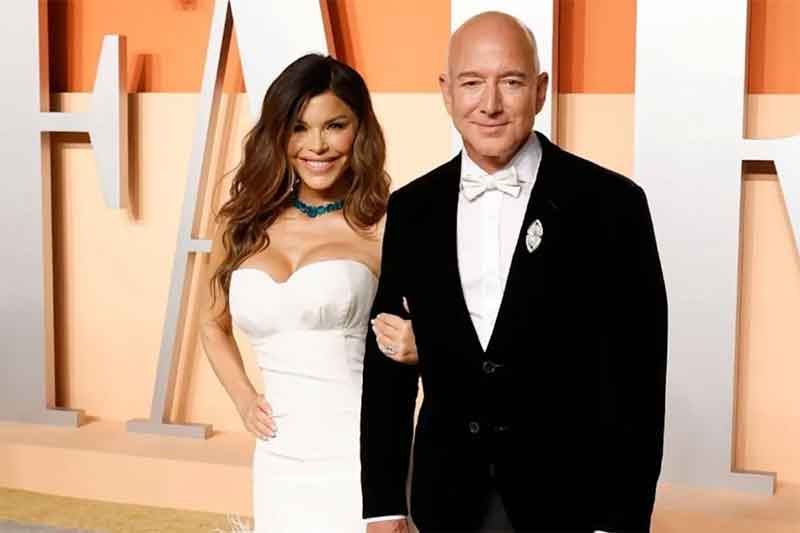

For years, I sustained a measured admiration for Bezos. His persona—that of the cerebral strategist, the relentless work ethic incarnate, the innovator embracing colossal risks—seemed to embody Max Weber’s “spirit of capitalism”: discipline channelled into productive enterprise. I respected his apparent aversion to vulgar ostentation; his early philanthropy, while arguably modest relative to his wealth, suggested a quiet Aristotelian virtue of megalopsychia (greatness of soul) expressed through discretion. Yet, this carefully curated image of ascetic genius began fracturing in the late 2010s. A stark volte-face emerged: the acquisition of a $23 million Kalorama mansion in Washington D.C. (2016), followed by a $165 million Beverly Hills estate—the most expensive home in California history (2020)—and the commissioning of the 127-meter sailing yacht Koru, whose final cost, including its support vessel, neared $500 million. This triad of acquisitions signals what sociologist Thorstein Veblen identified as “conspicuous consumption”—not merely wealth display, but a ritualistic assertion of status through wasteful expenditure. The transformation accelerated post-divorce from MacKenzie Scott, finding its most theatrical expression in his relationship with Lauren Sanchez. Their highly orchestrated public appearances, documented by paparazzi with tabloid fervour, transformed private wealth into a public spectacle, fulfilling Guy Debord’s prophecy of a “society of the spectacle,” where lived experience is supplanted by its mediated image.

The marriage of Jeff Bezos and Lauren Sanchez in Venice crystallised the apotheosis of neoliberal excess – a spectacle Guy Debord might have deemed the ultimate “concentrated spectacle,” where capital manifests its power through sheer, unapologetic lavishness. Estimates place the event’s cost near $50 million, a sum dwarfed only by its environmental and social footprint: over 200 global elites descended via armadas of private jets, helicopters, and mega-yachts, while five palazzo-hotels were exclusively commandeered and 30 of Venice’s finite motoscafi (water taxis) reserved from the city’s fleet of 280. Facing widespread protests decrying this assault on Venice’s fragile ecosystem and social fabric, Italy’s Ministry of Tourism defensively touted an alleged “$1 billion boost” to the local economy – a figure met with profound skepticism by economists, noting it likely conflates direct spending (estimated at $33.3 million for venues and guest outlays) with wildly speculative multipliers. The city’s deputy mayor amplified this dissonance, dismissing protesters as “narcissists” and championing the event as “high-quality tourism.” His jarring comparison – “We are not Iran… We have no moral police” – revealed a fundamental misreading of the dissent. Protesters weren’t demanding puritanical control; they were invoking principles of environmental justice and communal sovereignty. Their core demands were stark: an end to the flagrant violation of emissions laws (a single private jet emits 10-20 times more CO2 per passenger than commercial flights), a rejection of Venice’s surrender as a stage-set for plutocratic theatre, and a plea that their drowning city not be eternally branded by this filthy capitalist carnival – a grotesque embodiment of what Naomi Klein terms “disaster capitalism,” where elite indulgence accelerates amidst collective crises.

Let me be unequivocal: this is no polemic against joy or matrimonial splendour. Celebrations are cultural universals, and expenditure—even lavishness—holds its place in ritual. Nor is it mere class resentment; the true critique transcends envy. Yes, Venice profited tangibly—$33.3 million injected directly—yet this “billion-dollar boon” touted by officials echoes what David Harvey terms “the neoliberal gambit”: reducing a city’s worth to transient revenue while ignoring the social cost of its transformation into a rentable backdrop for oligarchic theatre. My disquiet stems not from the act of spending, but from its semiotics and scale. When the founder of a platform that once democratized access to the written word—a digital agora that brought Walter Benjamin’s dream of mechanical reproduction’s liberating potential to my Kashmiri doorstep—now orchestrates a $50 million spectacle amid a climate crisis, it signifies a profound moral inversion. This is Veblen’s “conspicuous waste” weaponised: 127-meter yachts and private jet armadas violating Venice’s fragile laguna while its citizens protest drowning streets. The tragedy is dual: Amazon remains my sole conduit to “the choicest books,” yet its architect embodies what Zygmunt Bauman called “the adoration of excess” in liquid modernity, where wealth isolates rather than elevates. My reverence wasn’t eroded by success, but by the commodification of grandeur and the abandonment of the very ethos of access that once inspired awe. The man who built a portal to global knowledge now builds monuments to its antithesis: exclusion.

The most insidious danger lies in the cultural normalisation of such extravagance. When oligarchic excess is framed as aspirational rather than aberrant—as with the Ambani nuptials in Mumbai, July 2024—it accelerates what Pierre Bourdieu termed the “symbolic violence” of late capitalism: the imposition of elite consumption patterns as societal ideals, eroding collective values of modesty and equity. This is not mere celebration; it is a pathology of wealth metastasising globally. Consider the grotesque dissonance: India’s richest family spent an estimated $600 million on a single wedding spectacle—equivalent to twice the annual budget of India’s National Nutrition Mission—while 229 million Indians survive on less than $2.15/day (World Bank, 2024). The former parliamentarian’s condemnation of this as “the most vulgar and ostentatious marriage ever seen” and the Kerala minister’s theological indictment—”a sin against the poor”—are not hyperbole. They articulate a rupture in the social contract. Such events weaponise culture, transforming tradition into a Disneyfied theatre of consumption accessible only to the planetary 0.001%. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai warns in “Modernity at Large”, when the global flow of images glorifies these rituals, they fracture local moral economies, replacing shared cultural meaning with commodified exclusivity. The Bezos-Ambani convergence reveals a harrowing truth: plutocratic weddings are no longer anomalies, but colonising rituals—erecting gilded walls where communal bonds once stood.

This pattern of extravagance operates as a cultural pathogen, mutating the very DNA of communal celebration. What begins as oligarchic theatre—obsession with designer couture, rare-ingredient gastronomy, and destination exclusivity—trickles down as a corrosive aspirational model. Pierre Bourdieu’s “Distinction’ reveals how such “taste hierarchies” weaponise consumption: the Ambanis’ ₹50 crore sari or Bezos’s Dom Pérignon iceberg sculptures become tacit benchmarks, transforming weddings from rites of union into performances of capital. The fallout is visceral: rising dowry deaths in India linked to inflated expectations (NCRB data: 7,000+ deaths annually); couples delaying marriage due to financial anxiety (Pew Research: 58% of Americans cite cost as primary marriage deterrent); and the quiet erosion of regional traditions displaced by Instagrammable homogeneity. Venice’s protesters articulated this moral vertigo: how can one reconcile €2,000 monthly pensions with €10,000-per-plate wedding galas? Italy’s wealth gap—where the top 1% holds 25% of national assets (Banca d’Italia, 2023)—mirrors a global malignancy. As Thomas Piketty’s r > g formula predicted, capital returns now systematically outpace wages. The result? A neofeudal chasm: plutocrats orbiting in private jets while nurses and teachers—the literal sustainers of society—work dual jobs to afford insulin or school fees. This isn’t mere inequality; it’s the unravelling of social cohesion.

The Venice spectacle’s profound ethical bankruptcy lies in its chronotopic dissonance—the violent collision of its temporal and spatial reality with a world ablaze. While Bezos and Sanchez exchanged vows aboard the Koru, Israeli airstrikes reduced Gaza’s last functioning hospitals to rubble. Since October 2023, over 56,000 Palestinians—70% women and children (UN OCHA)—have perished under siege. In Rafah, infants with ribs protruding like museum exhibits of starvation siphoned saline for sustenance; in Ukraine, $411 billion in infrastructure lies annihilated (World Bank); across Sudan and the Sahel, 40 million face famine (WFP). The philanthro-capitalist rebuttal—”We bear no duty to Gaza’s dying children!”—collapses under its own hypocrisy. When these same oligarchs performatively “donate” $100M to Maui wildfire victims or Houston flood relief, they engage in what critical theorist Slavoj Žižek terms “fetishistic disavowal”: “I know very well this suffering exists, but I act as though I do not see it when inconvenient.” Their compassion flows only toward disasters photogenically framed by Western media, never toward those their governments arm or abandon. The $50 million spent on Venetian decadence could have funded UNRWA’s entire Gaza food operations for 5 months (serving 2.2 million people). Such selective humanity isn’t just bias—it is the aesthetics of moral collapse, where oligarchs curate empathy like designer table settings.

Ultimately, these spectacles perform a sinister alchemy: they transmute obscene excess into aspirational normativity. What Venice witnessed was not merely a wedding, but the ritual consecration of a new feudal aesthetic, where oligarchic indulgence is framed as cultural triumph. This normalisation, as Judith Butler would argue, materialises power through repetition, etching deeper the grooves of social division. And as this aesthetic metastasises, the poor are not merely marginalised but erased into what Mike Davis termed “a planet of slums”—non-entities stripped of earth, belonging, and even grief’s visibility. The working-class alienation brewing beneath such displays is no longer Marx’s abstraction. When a single wedding’s floral budget exceeds a teacher’s lifetime earnings, culture itself becomes collateral damage in capital’s war on dignity. The tragedy is this: the man who once built bridges to knowledge now builds moats of indifference. Those books that found me in Kashmir? They now read as elegies for a world that chose golden yachts over shared horizons.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ghulam Mohammad Khan is a writer and academic from Bandipora, Kashmir. He holds a PhD from the Central University of Haryana, where his research focused on narratology and the interplay of memory in postcolonial storytelling.

Khan is the author of two books: Anecdote, History and Kashmir: And Other Essays (2025), a collection that interrogates dominant discourses through literary critique and counter-narratives, weaving Kashmir’s socio-political fabric into universal human struggles, and Elements of Literary Theory, an engaging introduction to key concepts and movements in theory and criticism.

His short stories and essays have appeared in The Indian Literature, Indian Review, Out of Print, KITAAB, and Kashmir Lit, among others. Fascinated by the subversive potential of language, Khan’s writing bridges scholarly rigour and narrative intimacy, often challenging static conceptions of identity and power.