The recent deaths of two white dwarf stars are challenging our understanding of both novae and the powerful physics underlying star death. According to astronomer John Monnier, the initial analysis of these often dramatic novae offers an “extraordinary leap forward” for the field.

“The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable,” said the University of Michigan astronomer and a co-author of a study published on December 5 in the journal Nature Astronomy. “It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.”

It takes two to nova. These spectacular moments occur after a dying white dwarf siphons off enough material from a nearby companion star. However, experts have long assumed novae ignite as a single, explosive event and two examples are contradicting that hypothesis.

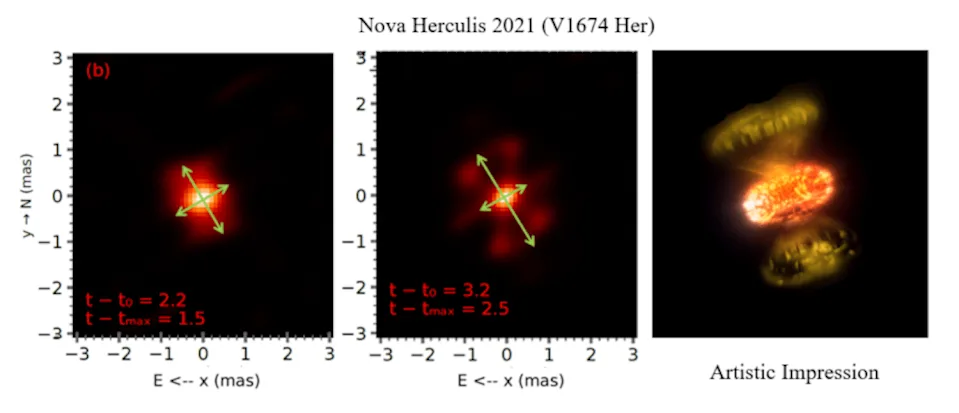

In 2021, researchers at the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array in California captured images from the eruptions of Nova V1674 Herculis and Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae.Herculis brightened and faded over only a few days, making it one of the fastest nova on record, but it also produced two perpendicular gas outflows. These jets imply that multiple, intermingling ejections powered the nova.

These same flows from Nova V1674 Herculis and Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae were also observed by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. However, Cassiopeiae went nova much more gradually in these observations. The star retained its outermost layers for over 50 days before ultimately ejecting them, offering astronomers the first direct evidence of a delayed nova expulsion. Like in the case of Herculis, Cassiopeiae’s gamma-rays were also recorded by the Fermi telescope.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time, something that is very complicated and has long been thought to be extremely challenging,” explained Texas Tech University astrophysicist and study co-author Elias Aydi. “Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”

The major breakthroughs are thanks to a technique called interferometry. The powerful technique lets astronomers compile light from multiple telescopes to sharpen image resolution enough to document quickly evolving and dynamic events like novae. In addition to the recent novae observations, interferometry is most famous for allowing researchers to finally image the Milky Way’s central black hole.

Although the new data likely upends some longstanding theories of novae behavior, experts say their findings will soon help expand our understanding of cosmic interactions.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy–they are laboratories for extreme physics,” added study coauthor and Michigan State University astronomer Laura Chomiuk. “By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”