When I sat down at my local coffee shop the other day, I had an epiphany.

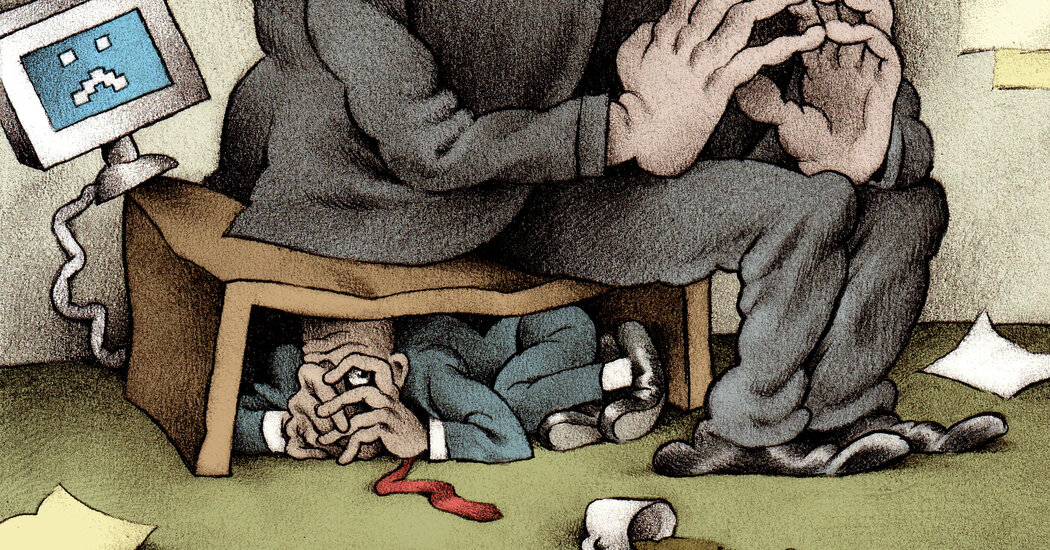

As I swirled a $3 house blend in a ceramic mug and waited on my friend Eric to arrive, I looked around at the anxious faces in the crowded shop and saw an America in an indeterminate state of being. Battered by a decade of economic and political uncertainty, buffeted by technological and social change, and besieged by an ever-growing list of existential threats, we are like the cat in the famous thought experiment about quantum physics.

You know the cat I’m talking about.

Schrödinger’s cat.

Waiting for Election Day 2024 has been its own type of hell, one in which uncertainty rules and the consequences are grave. We can take no comfort in the polls, given that most prognosticators consider the contest a dead heat.

It was two weeks before Election Day when I sat in the coffee shop on Commercial Street in Emporia and searched the faces of my fellow Kansans. They were young and old, rich and poor, and many of them wore their political allegiances on their sleeves.

An older woman in a four-wheel walker wore a black sweatshirt emblazoned with a photo of Trump, first raised in defiance, immediately following the July 13 assassination attempt in Pennsylvania. I did not know the woman and decided it would be intrusive, if not unpleasant, to ask about her apparel.

A person I did know, a bearded middle-aged man, walked quickly through the shop, perhaps trying to avoid the woman in the Trump shirt, but I don’t know if he saw her. He had been posting daily on Facebook several-hundred-word essays about his fear of another Trump presidency and his concern for the future of democracy. He had also been busy inviting others to unfriend him rather than argue in the comments.

Outside it was a beautiful fall day, but inside the coffee shop the looming election was like a toxic cloud that made it difficult to breathe. At least, that’s the way it seemed to me. Here we were approaching my favorite holiday — Halloween! — but my joy is hampered by polls with margins that have grown so close as to be practically nonexistent. Not that I trust polls, mind you, but I fear there is no sampling method up to the task of the modern digital lifestyle. An inaccurate poll is far worse than no poll at all.

There are no guarantees in any election, but not that long ago in ordinary times (let’s define that as between 1960 and, say, 2016) there was a reasonable expectation that no matter which party won, the Republic would continue. Now, there is strong evidence to suggest that should Donald Trump win, the American experiment in democracy may be over.

This is not hyperbole.

Recently, both Trump’s former chief of staff John Kelly and the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley were quoted as calling the ex-president a fascist. Trump has recently doubled down on his promise, if elected, to use the military against his domestic rivals and invoke the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport millions of migrants. He has called the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. capitol a “day of love,” ignoring the mayhem and deaths and the more than 700 individuals sentenced for their criminal activity that day. Trump himself is also a felon, having been convicted of 34 counts in a scheme to illegally influence the 2016 election through hush money payments to a porn star.

In my 100th Reflector column, back in March, I pondered the increasing fascination Americans have with fascism. I will repeat something from that column here, because I can’t say it any better:

But ultimately, Trump is not the problem.

The problem is us.

We’ve allowed ourselves to forget the lessons of 80 years ago, that the fascist path ultimately leads not only to death camps for perceived enemies but also to self-destruction. We are shredding the political and cultural norms that have kept Trumpian despots in check for a lifetime and are now flirting with the idea that perhaps disruption and violence are good things, creative things. That injustice and scorn for others and catering to a death wish is a coherent strategy for gaining and keeping power.

The Nov. 5 election is not so much a struggle between two candidates as it is a referendum on American democracy. That we as a nation are on the razor’s edge of indecision, according to polling, is a disturbing testament to an identity crisis of national proportions. Who, exactly, are we as a nation? What truths do we still hold to be self-evident, and do they truly belong to all or just the monied and influential few?

The scene in the coffee shop, so full of the everyday and yet so heavy with the weight of future history, made me think of scenes captured by artists in the distant past. “The County Election” by Missouri artist George Caleb Bingham, painted in 1852, is a portrait of democracy in action. Citizens of every class (well, white male citizens) rub shoulders on the steps of a courthouse to cast their votes, although some are obviously drunk or are recovering from fistfights. The original is displayed in the St. Louis Museum of Art, which notes on its website, “Bingham revealed what every American supportive of election understands: that the democratic ideal must be embraced even though (uninformed) votes could prevail.”

About a century later, regionalist Thomas Hart Benton portrayed hooded Ku Klux Klan members at a rally with an American flag. Part of “The Social History of Indiana,” the mural at Indiana University’s Bloomington campus was the target of student protests in 2017. While the space with the mural will no longer be a classroom, wiser heads recognized the art was authentic social commentary and the university opted to keep the mural intact.

What we have now instead of Bingham or Benton is an endless stream of self-inflicted digital photography. Selfies and memes dominate political discourse on social media, representing a narcissistic and reductive and perhaps toxic type of discourse. We still have news photos, of course, and the occasional bit of citizen journalism that shapes history, such as the Darnella Frazier video of the death of George Floyd, but largely our lived experience as Americans in the second decade of the 21st Century has gone unrevealed. We have documented our lives as never before possible, but have stopped short of meaningful examination.

Watching the faces in the coffee shop that day, I had an urge to start sketching, to try to capture the mood, to memorialize the feeling of this one day before the 2024 election so I could remind myself and others of its promise — or its folly.

But it would take a portfolio of sketches to attempt, even if I could draw.

Things change daily. Much of the news is so beyond the norms of past elections that it all has a dystopian edge, as if our reality had been imagined by Eric Blair or Aldous Huxley.

Of all the things I could cite, nothing is more mind-bending than the fact that the richest man in the world, Trump supporter Elon Musk, is giving away $1 million a day to registered voters in swing states who sign a petition supporting the First and Second Amendments. The Justice Department has warned Musk — or rather his PAC, which is running the lottery — that the activity might be illegal under federal law.

In addition to the legal question, there is the moral jeopardy of having a lottery for registered voters and giving away an oversized check at a partisan rally. This is the Hunger Games equivalent of civic duty. Where are those, including our own Kris Kobach, who claim to be so concerned about the integrity of voting, and yet keep silent about stunts like this?

At the coffee shop, between talking electric guitars and the new round of COVID shots, Eric says he feels the same kind of weight that I do about the upcoming election. But, he says, he is confident that Harris will win. When I express my doubts, he reminds me that he’s the one who told me Trump would win back in 2016, even though I considered Trump a joke.

I tell Eric I hope he’s right.

But here in deep red Kansas, my vote won’t matter much.

As Kansas Reflector opinion editor Clay Wirestone pointed out recently, the winner-take-all nature of the Electoral College will effectively cancel out half a million votes for Harris. The state’s six electoral votes will surely go to Trump. The last time Kansas played any part in electing a Democrat to the White House was in 1964, when Lyndon Johnson won by a landslide.

The fact that a handful of undecided voters in seven swing states have come to determine presidential elections is just one more absurd facet to our dystopian reality. Who could be undecided at this point? What more would they have to learn about the candidates? We are held hostage by the least informed and most indecisive among us, which is like giving the laziest reader in your high school English class a copy of “Ulysses” and basing everyone’s grade on their book report. Or, to put it another way, it would be like asking me to explain the rules of tennis.

Even though there is no suspense over the presidential election in Kansas, there are plenty of state and local issues on the ballot. Voters may even break the veto-proof Republican supermajorities in the Kansas Legislature.

So the cat may have some surprises yet.

In the 1935 thought experiment, physicist Erwin Schrödinger imagined a hypothetical cat in a sealed box whose fate depended on nuclear decay. In the box is a radioactive material that has a 50% chance of decay within, say, an hour. If a Geiger counter in the box detects any decay within the given time, a hammer will break a vial of poison, killing the cat. But you don’t know if the cat is alive or dead until you open the box at the end of the hour.

The point of this “ridiculous” experiment, as Schrödinger termed it, was to explain quantum superposition — the cat is both alive and dead until you look inside the box and the probability waves collapse into reality. I will ask the indulgence of my physics-minded friends for giving an overly simplistic explanation of the experiment. Also, I should make clear that no cat was ever harmed (or eaten by migrants) through Schrödinger’s mental exercise.

By the time this column is published, there will be just nine days before the election. Only 216 hours left of being in an indeterminate state. Advance voting has already begun, tens of millions of cats across the country sealed in boxes awaiting an observation to collapse probability into reality.

We do not yet know ourselves as a country. But soon we will.

Max McCoy is an award-winning author and journalist. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.