Joe Biden’s 50-year political career is one of the longest and most consequential in U.S. history. Along the way, Biden has often found the direction of his public life shaped by issues of race and by his handling of issues of particular concern to Black Americans.

During a 2016 Democratic presidential debate, then-Sen. Kamala Harris challenged Biden, her opponent for the party’s nomination, about a talk he gave on working with former colleagues who were segregationists and his record on school busing.

She posed some tough questions that included invoking her own experience of being a little girl who rode the bus to school as part of government policy to bring greater racial balance to public schools.

The theory was that in more racially diverse schools, Black children would be more likely to have equal educational opportunity than they would in predominantly Black schools that are frequently under-resourced.

Harris displayed the prosecutorial style developed during her years as San Francisco district attorney and as California attorney general. It was a style showcased as the U.S. senator questioned Trump administration appointees.

In the exchange with Biden, she alluded to the occasion during which Biden noted that he had worked with segregationist senators at a time he framed as less polarizing and more civil. Harris was reminding voters of how Biden had worked with and built personal relationships with Democrats and Republicans in the Senate who were or had previously been categorized as the Southern Democrats known as Dixiecrats.

These were segregationists who regularly voted against or filibustered civil-rights measures ranging from anti-lynching legislation to bills upholding voting rights and access to public accommodations.

“Vice President Biden, I do not believe you are a racist, and I agree with you when you commit yourself to the importance of finding common ground,” Harris said. “But I also believe—and it’s personal—it was actually hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and careers on the segregation of race in this country.”

Harris also accused Biden of trying to prevent the Department of Education from enforcing school busing to integrate schools during the 1970s, invoking her own experience to make the point. Biden responded by calling Harris’ remarks a “mischaracterization of my position across the board.”

“I did not oppose busing in America,” Biden replied. “What I opposed is busing ordered by the Department of Education. That’s what I opposed.”

Harris argued that the federal government must step in to keep civil rights from being violated “because there are moments in history where states fail to preserve the civil rights of all people.”

The moment was jarring for many Democrats, including Black Democrats whose affection for Biden had grown while he served as vice president and was part of what he and former President Barack Obama touted as a close working and personal relationship. Biden received steadfast support from Black voters in Delaware in all his U.S. Senate campaigns, but on matters such as busing, crime, policing and economic safety net issues, Biden sometimes took positions that ran counter to the views or interests of those constituents.

During the 2020 campaign, Biden found himself having to express regret for the tough-on-crime legislation he pushed in the 1980s and 1990s that proved so disastrous for Black communities. Little evidence exists to show that the policies made those communities safer. But they served to remove young men from communities with lengthy prison sentences, often for nonviolent drug offenses.

The policies meant the permanent loss of employment and educational opportunities for those men, harming generations of Black families. But over such a long career, Biden also took stances that won him praise from human-rights and civil-rights advocates. He led the fight in the Senate to oppose South Africa’s apartheid regime, taking on the Reagan administration and others that sought to defend it.

After Biden had twice run unsuccessfully for president, Obama chose him as his running mate, seeing him as someone well-connected to the Democratic establishment and to white working-class voters the party wants to keep as part of its coalition.

While vice president, his loyalty to Obama and his own political skills won favor among Black congressional leaders and Black voters that served him well during the 2020 campaign. Following the essential endorsement of U.S. Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina ahead of the state’s primary and his victory there, Biden cruised to the Democratic nomination.

Biden then made overtures to Black voters a central part of his campaign. He emphasized that a turning point in his decision to run for president in 2017 was former President Donald Trump’s response to the 2017 Unite the Right march of white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va.

The actions of those white supremacists led to the murder of Heather Heyer, a counter protester. Following Trump’s equivocation about those events, Biden said he decided to run for president in 2020 and engage in “a battle for the soul of America.”

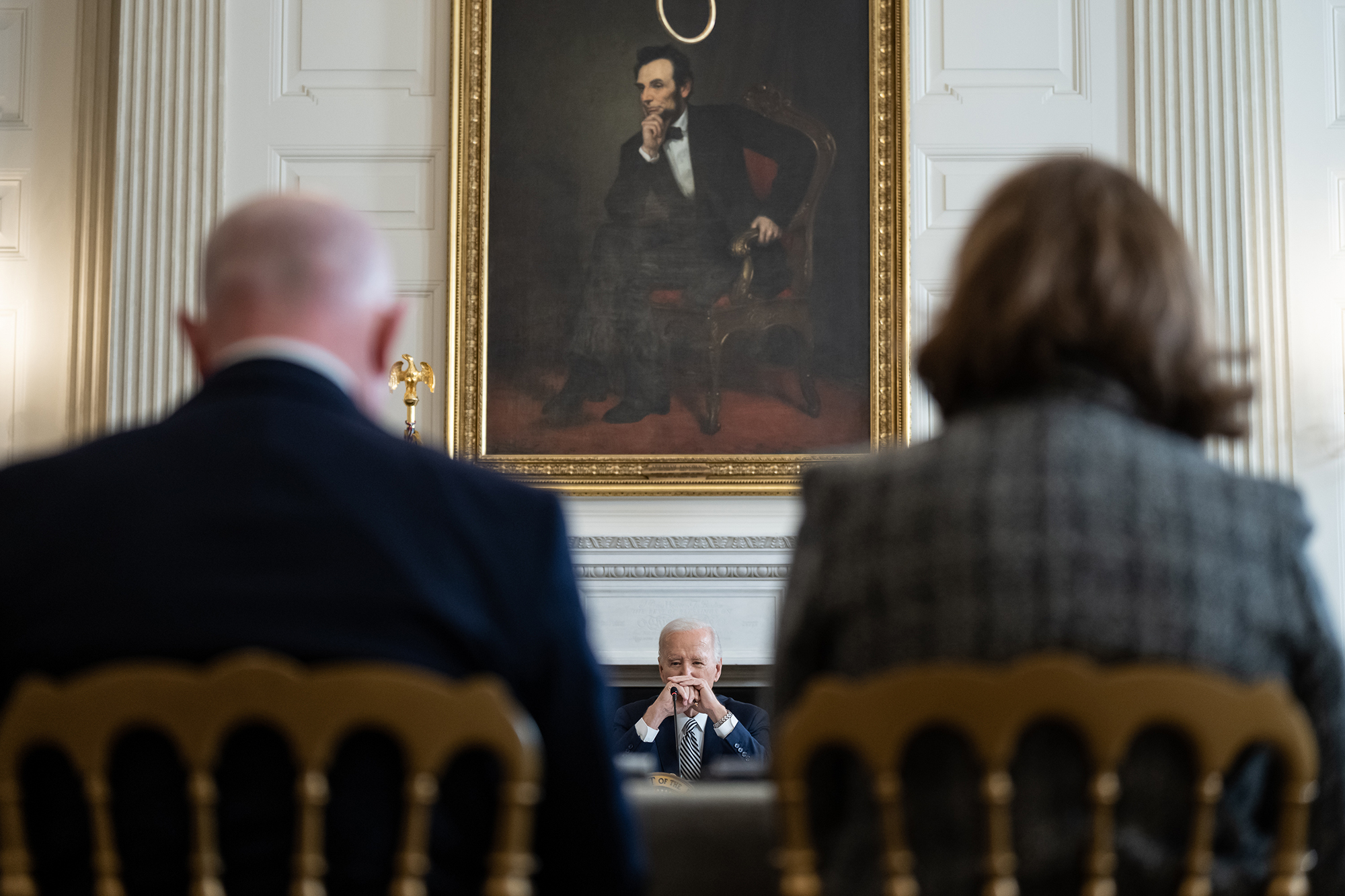

When Biden committed to putting a woman on the Democratic ticket, Harris was among several Black women under consideration. That tense debate exchange didn’t prevent him from ultimately choosing her as his running mate.

In fact, the way she challenged his record on a racial issue was seen as a major factor in her selection. Choosing her was a way of facing up to his own history. It was a way of demonstrating that he wouldn’t hold a grudge against Harris for holding him accountable for past positions and associations. It represented a personal reckoning.

His legacy will also include his commitment to appointing a Black woman to the Supreme court. He made good by nominating a highly regarded federal appeals court judge, Ketanji Brown Jackson. She became the first Black woman to ever serve on the high court.

Overall, Biden has appointed Black federal judges at a rate that surpasses any other president. He has appointed more Black lifetime judges than any previous president in a single term. The 59 Black judges he has appointed include 38 women. More than 40% of these judges bring to the bench significant experience protecting and advancing civil and human rights.

Since 2021, the Senate has confirmed 14 Black judges to federal appellate courts, including 13 Black women. Previously, only eight Black women had ever served at this level of the federal judiciary.

Biden’s administration has worked to make the federal judiciary more reflective of the country it serves. That effort comes at a time when the Supreme Court and lower courts have dismantled affirmative-action programs, in rulings on lawsuits conservative groups filed.

Conservatives are also speaking and working against any measures that would in any way compensate Black Americans for decades of racial violence and plunder. Biden’s administration has moved to begin a national reckoning with that legacy.

The Justice Department has launched a review and evaluation of the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, Okla., Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke announced.

White attackers killed as many as 300 people, most of them Black, in Tulsa’s prosperous Greenwood neighborhood, nicknamed Black Wall Street.

The review will be conducted under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act, under which the Justice Department will investigate racially motivated crimes that occurred on or before Dec. 31, 1979.

In August, Biden announced that the administration has made more than $2 billion in direct payments to Black and other nonwhite farmers the Department of Agriculture had discriminated against.

More than 23,000 farmers were approved for payments ranging from $10,000 to $500,000, the USDA reports. Another 20,000 who planned to start a farm but did not receive a USDA loan received between $3,500 and $6,000. Most payments went to farmers in Mississippi and Alabama.

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said the aid “is not compensation for anyone’s loss or the pain endured, but it is an acknowledgment by the department.”

Vice President Harris’ acceptance of her party’s nomination for president signified another moment of reckoning for the nation. She capped off one of the most remarkable months in U.S. presidential campaign history. In a matter of weeks, she largely unified the party behind her, ignited voter enthusiasm and by every indication, significantly boosted the party’s chances in November.

Her fellow Howard University graduates and Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority sisters got to witness and celebrate her moment. Her rise represents the impact Black institutions continue to have on American life.

That rise is also owed in part to decisions Biden has made during the past four years as he attempts to lead the country in confronting its history on race.

If the vice president wins in November, the history she makes will have a rightful place in the president’s legacy, too.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to voices@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.