One of the world’s richest men wants his newspaper to push policies that favour the rich. That’s the upshot of Jeff Bezos’s announcement today of a new regime at the Washington Post. Henceforth, the Amazon boss decreed, his paper’s comment pages will promote libertarianism (“free markets and personal liberty”), and will not publish opinions contradicting these central principles.

While the story has a dog-bites-man quality — breaking: tycoon prefers low taxes and weak unions — it’s still a dismaying turn. Since the Wall Street Journal comment pages (where I cut my teeth) are also strictly committed to free-market libertarianism, it leaves the New York Times opinion page as the only national print outlet where writers can argue for greater union density and more robust antitrust enforcement, say, or against Wall Street’s hollowing out of the real economy.

Bezos’s reasoning is ahistorical and infuriatingly self-serving. Free-market freedom, he says, is “ethical — it minimizes coercion”. That’s one of the big myths of modern libertarianism: the notion that coercion can only come from the government, while the market is a zone of perfect competition, in which everyone can always find a better deal elsewhere.

To see why that’s untrue, consider… Amazon. In 2020, the mega-retailer terminated the employment of Christian Smalls, a worker at one of its warehouses on Staten Island, New York, who had sought to organise his fellow workers. (In an internal memo, Amazon characterised Smalls, who is African American, as “not smart or articulate” — this, at the same time that the company took a leading role in corporate America’s Black Lives Matter advocacy).

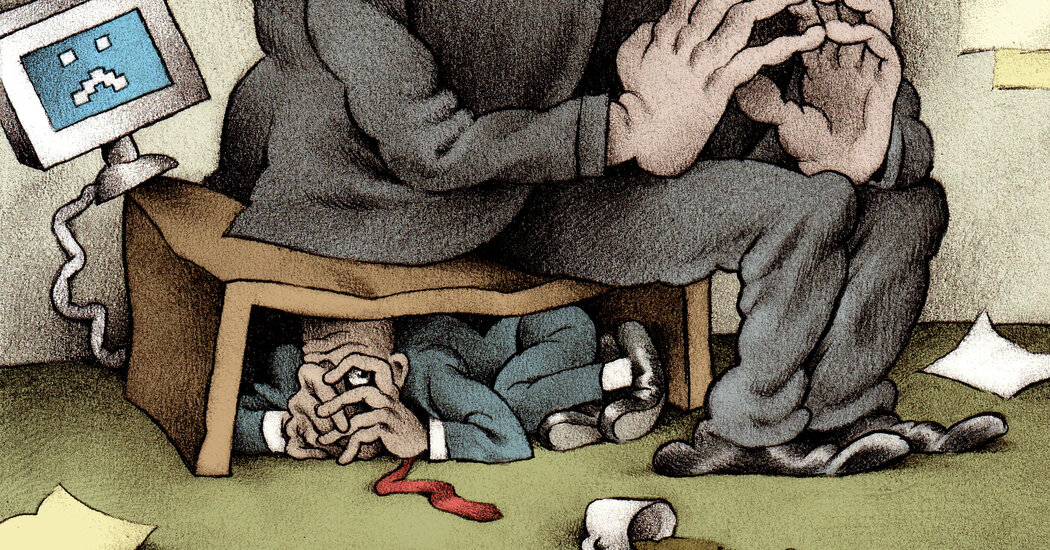

Why did Smalls resolve to mount collective action in the first place? By now, the Dickensian horrors of Bezos’s foundries are well-known. Bathroom breaks are often too short to permit workers to make it across the vast span of the warehouse and return to their work stations in time. Bezos offers his workers only a limited amount of “time off-task” and docks their pay for what Amazon calls “time theft”. Sometimes, this forces workers, especially older ones, to relieve themselves in bottles or in dark corners.

A managerial culture of fear is all-pervasive. “Amazon tracks workers’ every movement inside its warehouses,” reports the New York Times. Even top performers have been fired for as little as a single underproductive day. Even for managers who don’t ruthlessly dismiss workers, the explicit aim is to create an atmosphere of generalised terror, according to internal documents reviewed by the Times.

Meanwhile, on the cultural front, Amazon drew the ire of many conservatives and gender-critical feminists for its decision to delist Ryan T. Anderson’s 2018 book about transgenderism, When Harry Became Sally. The firm claimed, bizarrely, that Anderson’s scholarly work violated the firm’s policies against hate speech. After the 2024 election, Amazon began selling the book again.

Minimising coercion, indeed. The only meaningful defences against such abuses are countervailing power mounted by labour unions or government regulation. Yet the Washington Post will no longer host arguments in favour of such measures.

Beyond morality, Bezos waxes historical. “A big part of America’s success has been freedom in the economic realm,” he claims. That’s one of the shibboleths of modern libertarianism: an invented tradition used to retcon the American past to reflect Chamber of Commerce preferences on issues such as trade, immigration, and labour rights. In reality, US economic might and dynamism were built on Alexander Hamilton’s decidedly un-libertarian model. The Hamiltonian system relied on a strong state to protect manufacturing, weave together a national market, and ensure the flow of credit (i.e., tariff, canal, and the Bank of the United States).

There were proto-libertarian opponents of that system, to be sure, mainly in the Southern slavocracy. If they’d had their way, Britain would have defeated American industry, and the new republic would have remained little more than a swampy resource pool for European manufactures. In the event, it was heirs to the Hamiltonian tradition — the likes of Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, and Richard Nixon — who won that debate, bringing about a blended political economy that, at its best, encourages government, capital, and labour to cooperate for the national welfare.

That isn’t to deny a historical role for free enterprise. It’s merely to point out that prosperity resulted from the tension between material forces and ideals: state and enterprise, capital and labour, individual rights and solidarity. It would be one thing if a national newspaper like the Washington Post set out to give greater weight to the free-enterprise side of the ledger. But that’s not what Bezos’s new regime promises: “Viewpoints opposing [free markets] will be left to be published by others”, he wrote.

There is a rich irony in an oligarch touting his commitment to freedom in a memo narrowly restricting the range of views available at his paper.