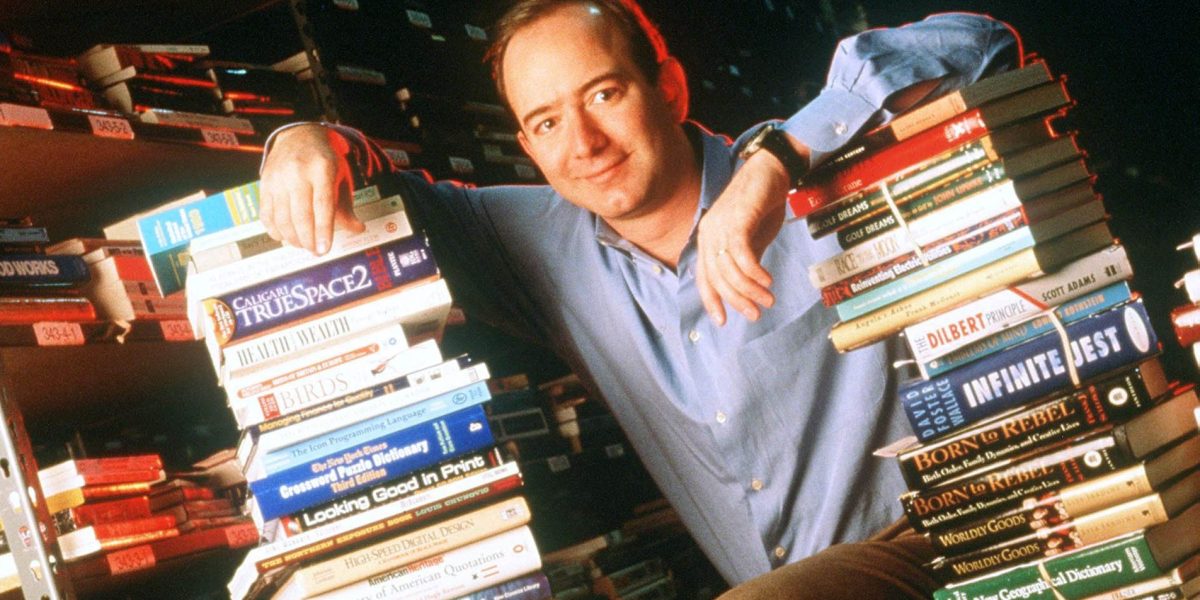

Jeff Bezos’ trajectory from a rented Bellevue garage to the helm of a $2.4 trillion enterprise is now business legend. In the summer of 1994, Jeff Bezos left a fledgling Wall Street career and moved to Bellevue, Washington, with a vision: to build an online bookstore that could one day sell everything. The first headquarters of Amazon was a modest rented house, and he and his then-wife, MacKenzie, worked side by side, packing books and driving them to the post office. The garage, with its concrete floor and humming servers, became the birthplace of what would soon be known as “the everything store.”

It also gave birth to Bezos’ mentality as Amazon founder, one that he would ingrain some day in his much larger company as “Day 1,” as in, every day of your job should be tackled as if the company was one day old and you were still in the garage. Success or failure could be just around the corner. Bezos worked from his own day one to institutionalize innovation, risk-taking, and data-driven iteration.

But looking beyond the garage mythology and the familiar narrative of entrepreneurial grit, Amazon’s ascent can also be understood as a product of uncanny anticipation of network effects, strategic long-term thinking, and relentless customer obsession. In fact, Bezos at one time wanted to name the company “relentless” and relentless.com still directs back to Amazon, the long river from which it all flows.

Paul Conors—AP Photo

Joshua Lott—Bloomberg/Getty Images

Team meetings at Barnes & Noble

In the early days, resources were scarce, and office space was at a premium. In those months, Bezos and his tiny team often held meetings at a local Barnes & Noble. The irony was not lost on them: the upstart online bookseller strategizing in the aisles of the nation’s largest brick-and-mortar book chain.

In 1996, as Amazon’s profile grew, Barnes & Noble’s founders, the Riggio brothers, took notice. They met with Bezos, expressing admiration but also warning that their own online venture would soon eclipse Amazon. Undeterred, Bezos doubled down on his vision, coining the motto “Get Big Fast” and setting his sights on rapid expansion.

By the time Amazon moved into official office space, Bezos leaned into the scrappiness, using recycled doors as desks for himself and his staff. He wanted to communicate that no resource goes unused or un-recycled. Amazon would be as thrifty as the deals that it gave to its consumers. It was also another way to bring the garage into the office space, another way to stress being relentless.

Photo Nomad Ventures, Inc.—Corbis/Getty Images

James Leynse—Corbis/Getty Images

The relentless drive to ‘get big fast’

Bezos raised capital from family, friends, and a handful of investors, giving up a significant stake in exchange for the funds needed to scale. The company’s first product was used books, chosen for their universal demand and ease of shipping. But Bezos’ ambitions were always bigger: he envisioned a store that could sell anything to anyone, anywhere.

Unlike many dot-com era founders, Bezos eschewed the lure of quick profits, instead prioritizing scale at the expense of short-term returns. His now-famous “regret minimization framework”—a decision-making process that emphasized acting now to avoid future regret—drove bold risks: forgoing personal profit, convincing early investors to back negative earnings, and building a fulfillment infrastructure whose costs initially seemed irrational. But this disciplined reinvestment cultivated one of the world’s most advanced logistics networks and primed Amazon to dominate not just books, but any commerce vertical it pursued.

Ken James—Bloomberg/Getty Images

Deb Cohn-Orbach—UCG/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Ted S. Warren—AP Photo

The ‘everything store’ emerges

By the late 1990s, Amazon had expanded beyond books, adding music, movies, and eventually a dizzying array of products. The company’s relentless focus on customer experience—fast shipping, low prices, and an ever-expanding selection—set it apart from competitors. Amazon weathered the dot-com crash, outlasted rivals, and continued to innovate, launching services such as Amazon Prime, Kindle, and Amazon Web Services (AWS), reflecting Amazon’s shift from single-product retailer to platform.

By opening the site to third-party sellers and launching AWS, Amazon became not merely a merchant, but an infrastructure for global commerce and cloud computing. AWS, in particular, is a case study in internal capabilities repurposed into external market offerings—a move that helped reshaped the economics of the internet itself. Amazon’s relentless drive turned it into something approaching a utility.

A $2.4 trillion empire

Today, Amazon is a global powerhouse, its reach extending from e-commerce and cloud computing to entertainment and artificial intelligence. As of July 2025, Amazon’s market capitalization stands at a staggering $2.4 trillion, making it the world’s fourth most valuable company.

Amazon’s impact transcends balance sheets, though. It has redefined supply chain expectations, influenced labor markets, and raised pressing questions around antitrust. Critics argue that the same mechanisms that fueled its rise—aggressive reinvestment, platform dominance, and data leverage—have also created structural dependencies with profound implications for competition, privacy, and labor.

Amazon’s true moat may be neither retail nor cloud computing per se—but its ability to seamlessly integrate physical and digital services into a single, adaptive operating system. It is working under Bezos’ successor Andy Jassy to add AI-driven services to the portfolio. It is relentless.

For this story, Fortune used generative AI to help with an initial draft. An editor verified the accuracy of the information before publishing.