BERLIN—President Trump’s ambitions on Greenland have drawn blowback from the very parties that had most enthusiastically embraced his populist revolution.

In responses ranging from delicately calibrated to brusque, nationalist and antiestablishment figures from the U.K. to France, Germany and Italy have pushed back against Trump, while at times blaming their domestic opponents for mishandling the trans-Atlantic flare-up.

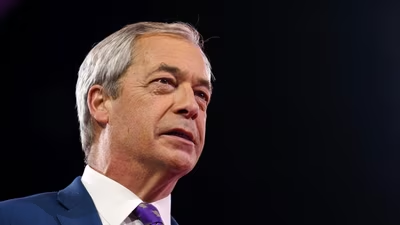

Nigel Farage, head of Britain’s populist Reform UK party, which has close ties to the U.S. administration, called Trump’s Greenland takeover bid a “very hostile act.” Jordan Bardella, a leader of France’s right-wing National Rally, said it amounted to coercion. And Alice Weidel, one of the leaders of the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, accused Trump of going back on his campaign promises.

The moment was perhaps inevitable. Parties that are shaped around giving priority to what they see as their national interests are bound to clash at some point. There has never been a lasting international brotherhood of nationalists.

“Quite a lot of [these parties] were formed in one form or another of opposition to U.S. imperialism,” said Jeremy Shapiro, who heads the Washington bureau of the European Council on Foreign Relations. “They are sovereigntist parties who are acutely jealous of their nationalism and don’t like to be dominated by anyone if their idea is to make their country great.”

Still, it is a risky moment for an antiestablishment movement whose ascendance has until now seemed unstoppable. Push back too hard and it could lose the patronage of the Trump administration, which has pledged to help what it calls patriotic forces achieve power in Europe.

Act too supinely and it could alienate voters who, polls show, are growing increasingly incensed at the friendly fire pouring out from Washington, said Peter Matuschek, director of Germany’s Forsa polling group.

“I would think that at the moment, it would help any party if they took a clear stand against Trump,” Matuschek said. “And possibly even the right-wing parties.”

A Forsa poll conducted after the Greenland dispute broke out and published on Tuesday showed 71% of German voters now considered the U.S. an adversary instead of a partner. For the first time, a majority of supporters of AfD agreed.

The leaders of the AfD, who have forged some of the closest ties between a European opposition party and Trump’s MAGA movement, have been walking a tightrope. Alice Weidel, the AfD’s co-leader, condemned the U.S. raid on Venezuela, Trump’s claims on Greenland, and his threats—later withdrawn—to raise tariffs on Germany and the other European countries that backed Denmark in the dispute.

After Trump’s U-turn on Greenland on Wednesday, Weidel’s co-chair, Tino Chrupalla, hammered the same message, saying “German interests aren’t aligned with America’s.”

Speaking while on a visit to Washington, Gerold Otten, an AfD lawmaker, said, “This is a delicate situation, because the AfD of course defends German interests, and they are being directly threatened right now.” But, he added, “we shouldn’t couch this defense as criticism of the U.S.”

Of all opposition right-wing parties in Europe, the AfD has received the most support from the Trump administration. This means it has a lot to lose.

Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and former Trump adviser Elon Musk have all publicly supported the AfD over the ruling coalition of Chancellor Friedrich Merz. Musk appeared at an AfD rally before last February’s election in Germany and explicitly called on voters to elect the party, helping broaden its appeal.

In its new national-security strategy, published last year, the U.S. said it would support “patriotic European parties” and cultivate “resistance to Europe’s current trajectory within European nations,” phrases widely seen as signaling the endorsement of the European far right.

Asked about Trump’s tariff threats, the U.K.’s Farage said this week, “It’s wrong, it is bad, it would be very hurtful to us.” The populist leader has said he would broach the subject with U.S. officials in Davos, Switzerland, this week.

Speaking in Davos on Wednesday, Trump maintained the U.S. claim on Greenland but later wrote in a social-media post that he would lift tariffs on Denmark and its allies after agreeing with NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte on “the framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland.”

The leaders of National Rally, a strong contender to win next year’s French presidential election, have been unequivocal in their condemnation of Trump. The response from one of the largest and oldest right-wing antiestablishment parties in Europe partly reflects France’s Gaullist tradition as having “among the strongest sense of independence from the United States,” said Shapiro, of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Marine Le Pen, the party’s former chair and head of its parliamentary group, has slammed the U.S. raid on Caracas, saying “the sovereignty of states is non-negotiable…It is inviolable and sacred.”

Before Trump suspended his tariff threat, Bardella, the party’s chairman and French presidential hopeful, even urged the EU to retaliate by scrapping last summer’s trade truce with the U.S. and deploying its so-called bazooka—anticoercion measures originally developed to counter Chinese influence.

“When a U.S. president threatens a European territory while using trade pressure, it is not dialogue—it is coercion,” Bardella said in the European Parliament. “Greenland has become a strategic pivot in a world returning to imperial logic. Yielding today would set a dangerous precedent, exposing other European—and even French overseas—territories tomorrow.”

The few Trump allies to have achieved power in Europe have faced the same constraints as all other European leaders when managing the U.S. president’s regular outbursts. In the middle of a trip to South Korea when the Greenland crisis broke out, Italy’s right-wing prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, called on Trump and Rutte to lower the temperature.

The decision by the European countries to dispatch soldiers to Greenland last weekend reflected the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s determination to secure the island but was misinterpreted as a hostile act by the U.S., Meloni said, adding that Trump’s threatened tariffs were “a mistake.”

There is one upside for euroskeptic politicians. One European diplomat said this week that should Washington end up acquiring Greenland, it would strengthen the charge that the EU is incapable of defending the continent’s core national interests.

Robert Fico, the anti-EU prime minister of Slovakia, visited Trump in Mar-a-Lago on Saturday, the day Trump issued his tariff threat. After his return, he called Merz to discuss the risk fresh tariffs would pose to the Slovak economy, which depends heavily on German car factories. His message: It is all the EU’s fault.

“The President of the United States is clearly pursuing the nation state interests of the U.S. If the EU acted in the same way, we would be in a completely different position,” Fico wrote on X after his call with Merz.

Write to Bertrand Benoit at bertrand.benoit@wsj.com