The Biden administration took what it called a “small yard, high fence” approach to the U.S.’s tech rivalry with China: It erected strict barriers to prevent U.S. companies from selling advanced chips and other critical know-how that Beijing could exploit to strengthen its military and surveillance capabilities, but otherwise allowed business to proceed as usual.

Backers of the policy thought it would keep the U.S. ahead in technologies such as artificial intelligence.

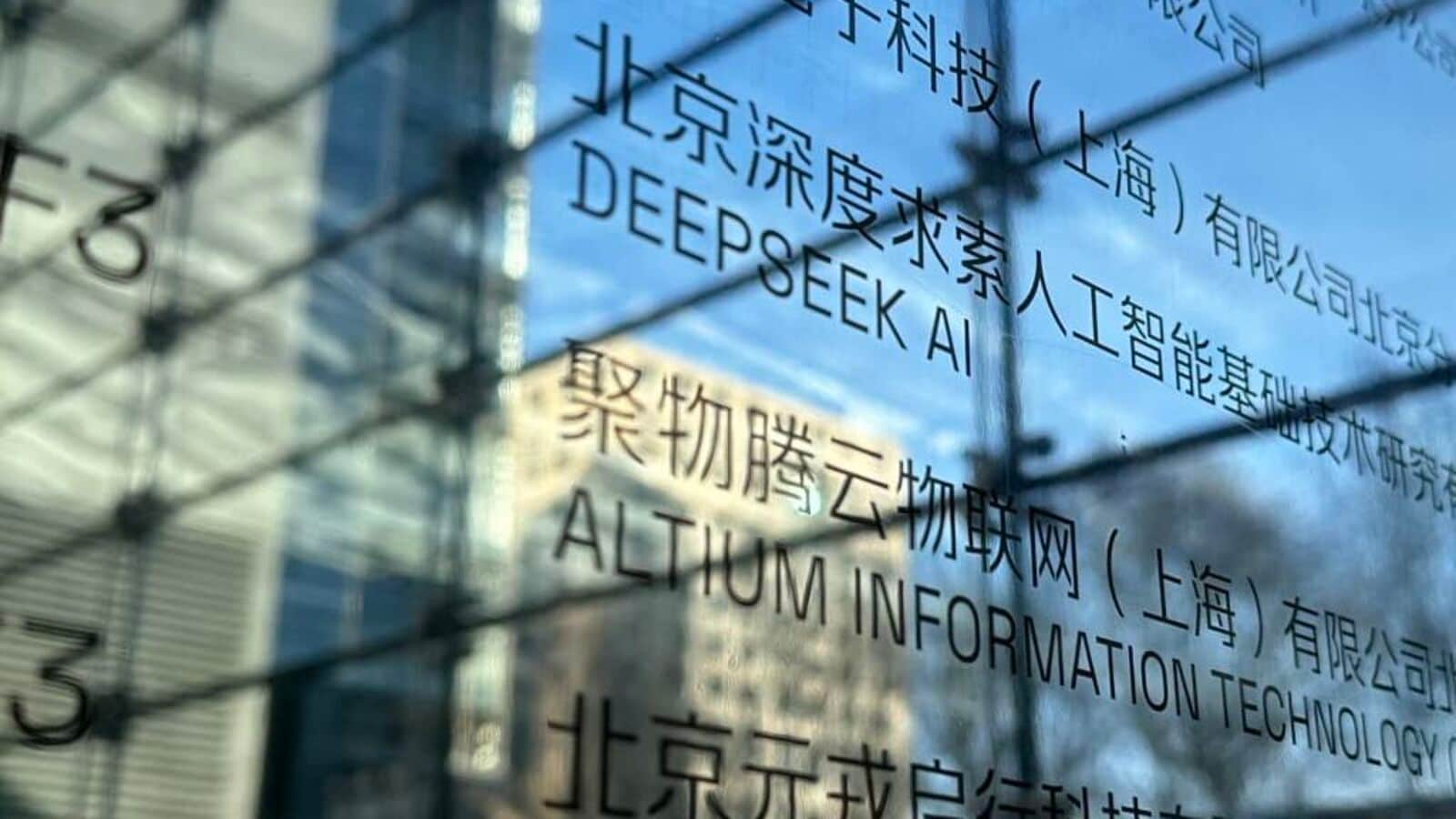

But now DeepSeek has blasted through the barriers, releasing a low-cost AI model that rivals American achievements. Its success is fueling debate over whether the U.S. needs a new approach, with DeepSeek serving as a Rorschach test for people with differing beliefs about the best way forward.

Backers of a hard line against China say that DeepSeek was able to use deficiencies in the Biden administration’s rules to accumulate chips it shouldn’t be able to access. The logical way forward, some argue, is for Washington to double down with even tougher rules to ensure Chinese companies can’t access advanced U.S. technology in the future.

Others say DeepSeek’s progress only encourages China to work harder to innovate while depriving American companies of revenue.

It is a position China itself is now proclaiming. “Trying to curb technological development by restricting hardware is like trying to dam a large river while overlooking the countless streams that feed it,” the Communist Party-run Global Times wrote in a commentary on Monday.

There are people from both camps among Trump’s advisers, and it remains unclear whose views will prevail with the president, according to industry watchers. Last week, his administration said in a memo that it was reviewing policies to maintain America’s leadership in AI innovation and would recommend a strategy in about six months.

“I’m confident in the U.S. but we can’t be complacent,” David Sacks, Trump’s AI and cryptocurrency czar and one of the three Trump officials leading his AI strategy, wrote in a post on X. He noted that Trump had already rescinded a Biden executive order that required AI developers to report the results of safety tests on systems that posed risks to U.S. national security, the economy, public health or safety.

The Biden order, Sacks said, “hamstrung American AI companies without asking whether China would do the same.”

But DeepSeek’s breakthrough also gives the China hawks in Trump’s administration more ammunition to push their views, said Steve Feldstein, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Alexandr Wang, the head of Scale AI, a San Francisco-based AI startup, called for a tightening of U.S. export restrictions to allow the country’s companies to maintain their lead in the technology. Yet he also warned that the U.S. needs to avoid leaning on export controls as a crutch, and instead work harder to outrun its rival.

“DeepSeek is a wake up call for America, but it doesn’t change the strategy,” Wang wrote on X. Ultimately, the U.S. just needs to “out-innovate & race faster.”

Trump could tighten the screws through additional restrictions on China’s access to semiconductors, or by requiring chip companies to add the ability to track the location of export-controlled semiconductors, according to Matt Pottinger, a deputy national security adviser in the first Trump administration who is now head of research firm Garnaut Global.

U.S. officials could also slap stiff penalties on companies to deter them from undermining the controls, he said.

The release of DeepSeek’s chatbot app, which hurdled past OpenAI’s ChatGPT to take the No. 1 spot in the Apple Store, helped The DeepSeek model, R1, matches or nearly matches the performance of the U.S.’s top AI models in solving complex problems, according to third-party evaluations. But it was produced at a fraction of the cost: less than $6 million, according to DeepSeek, compared with $100 million or more for its American competitors.

On Wednesday, Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba claimed that a newly released version of its own AI technology surpasses DeepSeek’s model across various benchmarks, underscoring the potential for others to catch up.

Part of the challenge for U.S. policymakers is that it is still not entirely clear how much of DeepSeek’s success relied on accessing U.S. technologies, and how much came from its own innovations. OpenAI said Wednesday it is investigating whether DeepSeek trained its new chatbot by repeatedly querying the U.S. company’s AI models.

In a research paper from December, DeepSeek said it used more than 2,000 of Nvidia’s H800 chips to train one of its AI models. Nvidia had rolled out the H800, a stripped-down version of what was then its most powerful chip, to comply with U.S. export controls that were imposed during the Biden administration to slow China’s technological progress. A year later, U.S. officials outlawed the chip entirely, but not after DeepSeek had about a year to buy such processors.

Some industry analysts say it is hard to establish without further investigation how many advanced chips the company actually used while training its models.

DeepSeek hasn’t responded to multiple requests for comment.

In addition to banning China from buying the world’s most cutting-edge chips, and the equipment to make them, the Biden administration added hundreds of Chinese entities to a trade blacklist and introduced investment curbs on Chinese AI, semiconductor and quantum computing companies.

It also initiated a trade investigation into China’s production of mature chips, and progressively tightened export limits on AI processors until Biden’s last week in office.

Industry researchers such as Dylan Patel, founder of chip researcher SemiAnalysis, say the Biden administration’s approach helped slow China’s progress in some areas, including developing cutting-edge chip making. Still, Patel said Biden’s export-control policies were plagued by delays and loopholes, which allowed the Chinese continued access to banned technologies.

Another challenge for the U.S. is determining where to draw the line: to only try to prevent China from technological advances that could aid its military, or a broader approach that seeks to limit Chinese advances in the commercial realm that pose a threat to U.S. companies.

“I think we may be moving more and more in a direction where the U.S. government simply decides that the entire Chinese tech ecosystem should not develop certain capabilities, regardless of the specific national security risks associated with individual companies,” said Rebecca Arcesati, senior science and technology analyst with Mercator Institute for China Studies, a German think tank.

—Stu Woo and Clarence Leong contributed to this article.