“China has given our elites far more than thirty pieces of silver, but everything comes at a price,” Senator Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) writes in his new book, “Seven Things You Can’t Say About China” (Broadside Books, Feb. 18). Cotton, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Chairman and an Army veteran, details how China is the most serious threat to our freedom and yet, he writes,”[American] elites bend the knee to Communist China and often act as de facto accomplices in Beijing’s crimes. And it cuts across all segments of American society.” Here, in an excerpt, he reveals the myriad ways the entertainment industry has done China’s bidding.

Hollywood’s notorious kowtowing to China has muzzled America’s most popular art form and brought actors, directors, and studio executives to heel. As a result, Hollywood hasn’t released a movie featuring China as the villain in more than a generation.

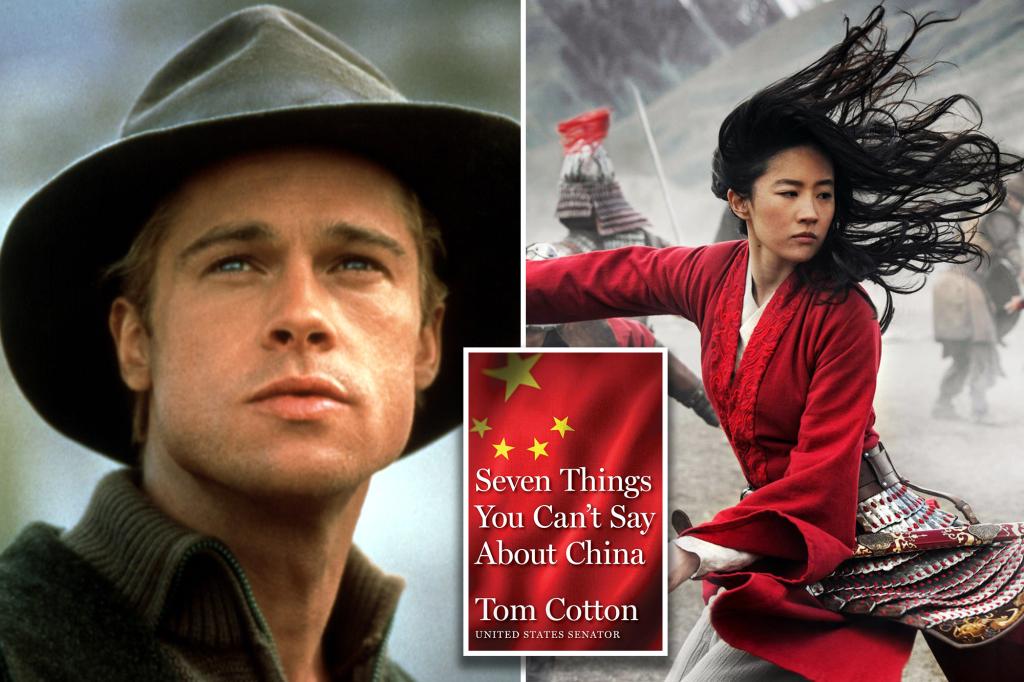

The Chinese Communist Party effectively conquered Hollywood in 1997. Sony Pictures released “Seven Years in Tibet,” starring Brad Pitt, and Disney released the Martin Scorsese–directed “Kundun.” Both films criticized China’s genocide in Tibet and favorably portrayed the Dalai Lama. China retaliated furiously, banning Disney- and Sony-affiliated Columbia Tristar from China, barring Scorsese and Pitt from traveling to China, and threatening to expel all Sony employees from the country.

Instead of standing by their films and their supposed principles, both companies buckled. Disney suppressed the release of “Kundun,” opening the film in just two theaters on Christmas Day. Disney’s CEO, Michael Eisner, traveled to Beijing for a groveling apology, calling the film a “stupid mistake.” Sony tried to buy absolution by lobbying for China’s entry into the World Trade Organization and plying Chinese officials with gifts.

This self-abasement ultimately earned Disney and Sony a reprieve from China, and earned China billions of dollars in investment from both companies, but the precedent was set. The party proved that it could and would throttle major Hollywood studios that crossed it. And the party has maintained a boot on Hollywood’s neck ever since, strictly controlling what films are released in China’s massive and lucrative movie market. China can also imperil other studio assets inside its borders, like Disney’s theme parks in Shanghai and Hong Kong. This story and its lasting consequences of “preemp- tive obedience” are told in Erich Schwartzel’s Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy.

These days, Chinese censors rarely need to suppress movies because American filmmakers do it themselves. Movie projects casting even the slightest aspersions on China rarely escape the planning stages.

But such movies still occasionally bubble to the surface, with results both telling and comedic. Consider, for instance, MGM’s 2012 remake of the 1984 Cold War classic “Red Dawn.” In the original film, heroic American teenagers fight to protect their community and country after a Russian invasion. In the remake, the young Americans battle a Chinese invasion—that is, until MGM’s executives intervened. Fearing Chinese retaliation, they digitally altered Chinese flags and insignia and made North Korea the invading bad guys instead of China. Who would’ve imagined that an impoverished, starving nation of just twenty-five million people could conquer vast portions of America with its fleet of fishing dinghies? Hollywood execs, that’s who, if that’s what it takes to do business with Communist China.

Other examples abound. The makers of the 2013 movie World War Z changed the origin of a zombie outbreak from China (as it was in the book of the same name) to North Korea. After all, who could believe that a global viral pandemic could start in China?

In the Marvel blockbuster “Doctor Strange,” the British actress Tilda Swinton plays the role of “the Ancient One,” who in the Marvel comic books has Tibetan origins, but in the movie does not.

One of the film’s screenwriters explained the decision to sanitize the character: “If you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that he’s Tibetan, you risk alienating one billion people … and risk the Chinese government going, ‘Hey, you know one of the biggest film-watching countries in the world? We’re not going to show your movie because you decided to get political.’” As if self-censorship weren’t the actual “political” deci- sion. And Marvel, of course, is owned by Disney.

Hollywood even lends subtle support for Communist China’s controversial policies. For instance, Disney famously filmed the 2020 movie “Mulan” in Xinjiang and during the end credits thanked eight Chinese government entities, including the public-security bureau of a city operating more than a dozen concentration camps.

Another common practice is needlessly displaying the “nine-dash line,” a preposterous map outlining China’s spurious claims to the entirety of the South China Sea, including the territorial waters of every other nation bordering the sea. The 2019 animated children’s movie “Abominable” and the 2022 movie “Uncharted” featured a version of the nine-dash line, and the 2023 blockbuster Barbie appeared to as well. In response, various combinations of the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam banned the movies from their countries.

With “preemptive obedience” the order of the day, China expects abject apologies from any Hollywood figure who missteps. In 2021, for example, the actor John Cena inadvertently referred to Taiwan as a “country” while promoting the release of “Fast & Furious 9.” Fearing that China might ban the film, he released a video begging forgiveness in Mandarin, “I made a mistake, I must say right now. It’s so so so so so so important, I love and respect Chinese people. I’m very sorry for my mistakes. Sorry. Sorry. I’m really sorry. You have to understand that I love and respect China and Chinese people.”

Mao described the Communist perspective on art succinctly when he said that there is “no such thing as art for art’s sake.” Xi Jinping has added that “the literary and art front is a vital front of the Party and the people.” Like everything else, art is simply another tool to strengthen the party’s rule. What’s remarkable is that the Communists have warped not only Chinese art to this purpose, but American art as well.