As combines roll across soybean fields at the start of harvest, exports typically pick up. Vessels ladened with the U.S. oilseed usually begin heading to China, with the bulk of shipments made between September and January.

That’s not shaping up to be the case this year.

Not a single order for the U.S. soybean crop was placed by China at the start of harvest in September.

At about the same time, Brazil set a record for shipments to China – with sales of 2.474 billion bushels of soybeans – from January through August 2025, reports Michael Langemeier, Purdue University ag economist.

Brazil soybeans have accounted for approximately 93% of China’s total soybean imports this year, to date, according to Brazil’s National Association of Grain Exporters.

‘A More Reliable Source For Soybeans’

Langemeier expects Brazil to continue supplying the majority of China’s import needs for soybeans, a transition he says has been underway since the last round of U.S.-China trade tensions in 2017-18.

“Brazil has become a more reliable source for soybeans, if you will, than the U.S.,” Langemeier says.

He does anticipate U.S. soybean exports to China will resume eventually but not at previous levels.

“I don’t believe it’s going to go to zero – people ask me that all the time – but it’s going to be something less than what it was prior to 2025,” he says.

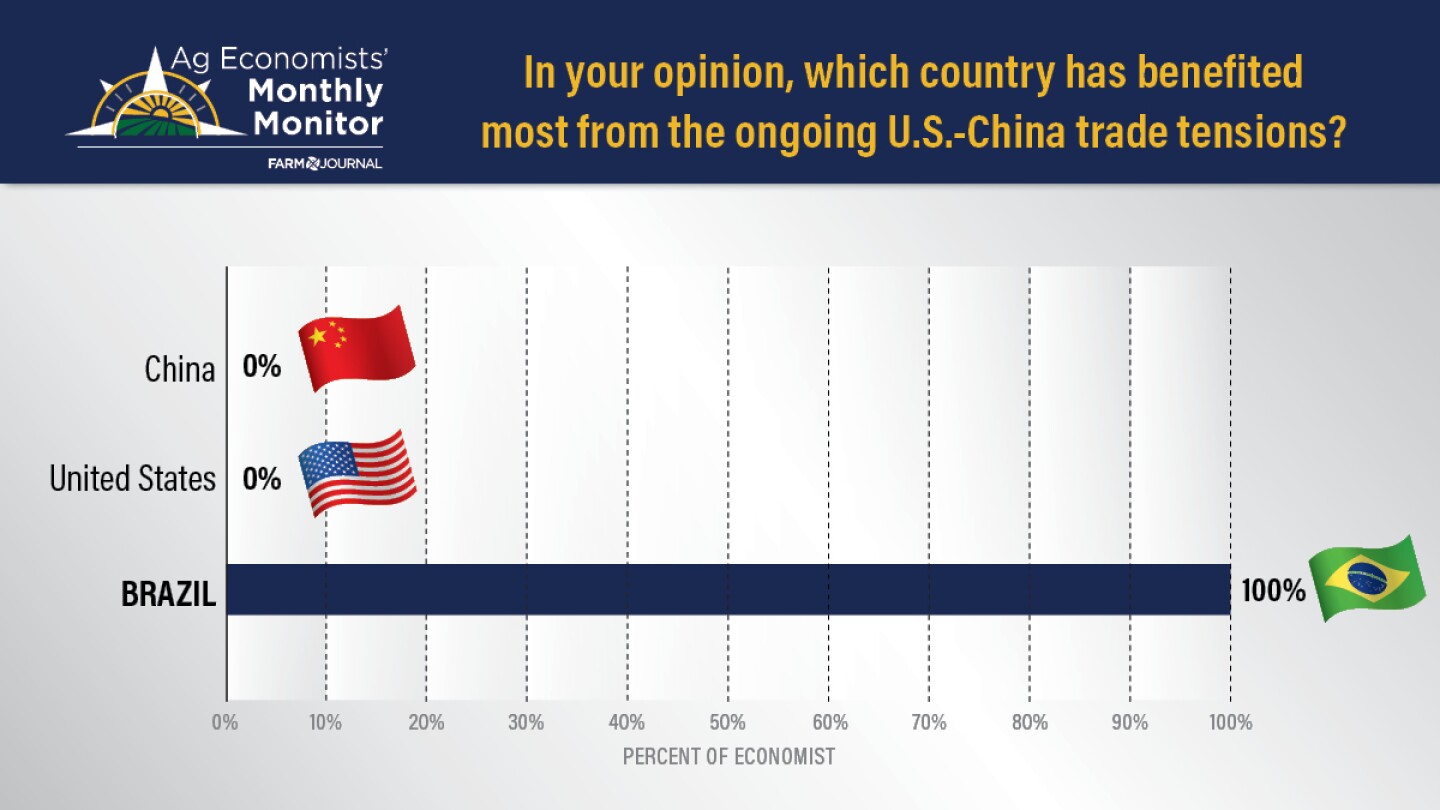

A large percentage of U.S. ag economists agree with Langemeier. In the latest Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor, when they were asked, ‘Do you believe U.S. agricultural exports to China will return to pre-trade war levels (e.g. 2017) in the future,’ 88% of economists responded no. Learn more here: Ag Economists Warn of Lingering Farm Economic Strain: ’Not the 1980s, But Close’

The ability of Brazil to capture more of China’s soybean business and improve its government policies pertaining to agriculture, in general, frustrates Steele, N.D., farmer Chase Dewitz.

“There’s so much progress going on there in agriculture in Brazil, outside of all the market share they’ve taken from us,” says Dewitz, referencing the country’s ethanol industry. “And here we just sit. We just keep getting backed into a corner here.”

China Prioritizes Its Own National Interests

Sandro Steinbach says China’s refusal to buy U.S. soybeans this fall is less about economics and more about politics.

“China is making a calculated move to limit its dependence on the United States,” says Steinbach, associate professor and director of the Center for Agricultural Policy and Trade Studies at North Dakota State University.

“If Chinese leaders see Washington as a strategic threat, they have the resources to pay a little more for Brazilian soybeans or draw down state reserves,” he contends. “It’s about control and national leverage, not about getting the cheapest beans.”

Steinbach adds, in an effort to not be overly reliant on either Brazil or U.S., Beijing is also working to reduce its overall need for imported soybeans through domestic feed policy changes.

“Our latest analysis shows Chinese feed mills are exploring ways to lower the share of soybean meal in livestock rations, with limited pilot programs already underway in several provinces,” he says. “If those efforts expand, even small cuts in feeding intensity could trim import needs, but they come at a cost. Lower-protein rations reduce feed efficiency and could hurt China’s livestock productivity over time.”

Faith Parum, American Farm Bureau Federation economist, points out that the ongoing trade tensions between the U.S. and China aren’t limited to soybeans. She says China has not “purchased any U.S. corn, wheat or sorghum this year, and pork and cotton exports continue only at reduced levels.”

USDA projects that U.S. agricultural exports to China will total $17 billion in 2025, down 30% from 2024 and more than 50% from 2022. In 2026, exports to China are expected to fall to just $9 billion, the lowest level since the 2018 trade war, Parum adds.

Trade Talks Next Week Offer Hope

Jacquie Holland, American Soybean Association economist, says upcoming meetings between President Trump and China’s Xi Jinping at next week’s APEC summit in South Korea offer farmers some encouragement that trade between the two countries will resume soon.

“If we see a de-escalation of tariffs, then China will have financial incentive to buy cheap U.S. soybeans,” Holland says.

She adds that if Brazil farmers have any delays harvesting their crop early in 2026, the Chinese could face a potential supply crunch and move to source U.S. soybeans to bridge the gap.

“But our research suggests those volumes could be minimal, based on the high volume of South American purchases China has made so far in 2025, the capacity of their state reserves, the timing of China’s hog production cycles and negative Chinese crush margins right now,” Holland says.

Farmers across Brazil have begun planting the 2025/26 crop season, with expectations for another record in corn and soybean acreage, report Purdue Ag Economists Langemeier and Joana Colussi.

“In its preliminary estimate released on October 14, the National Supply Company (Conab) projected that Brazil’s soybean acreage will increase by 3.5%, reaching 121 million acres – the largest area on record. For comparison, U.S. farmers planted 81 million acres of soybeans in the current crop season,” Langemeier and Colussi write here.

If Trade Doesn’t Resume Soon, What Then?

Unfortunately, there is no one country or market that can absorb China’s lost U.S. soybean purchases.

“There are certainly opportunities for some market expansion, as evidenced by Japan’s sentiments to increase trade on Wednesday, but the biggest constraint is that demand outside of China is limited in the short-run,” Holland says. “Long-term, we are hoping to develop these markets, but that takes time and doesn’t provide immediate relief to U.S. farmers now.”

Looking ahead to next spring, farmers are likely to plant another huge corn crop if a trade agreement isn’t reached and soybean prices remain in the basement, Langemeier anticipates.

“In that scenario, if we have two big years of corn production back-to-back, you’re going to be looking at some very sick corn prices in the fall of 2026,” he says. “That’s a big concern. That worries me.”

Holland adds there are other factors to consider, as well. She believes soybean acreage next spring will also depend on usage factors like how quickly EPA finalizes 2026 and 2027 renewable volume obligations for biofuel blendings and how fast the U.S. can expand domestic livestock consumption and export sales for soymeal.

“With all of that uncertainty and sticky input prices, I wouldn’t blame farmers for picking lower risk acreage options next spring, and I’m guessing 2026 acreage allocations are going to rightly reflect that level of risk aversion,” she says.

Holland discusses the soybean trade outlook with China in detail with Chip Flory, host of AgriTalk, here: