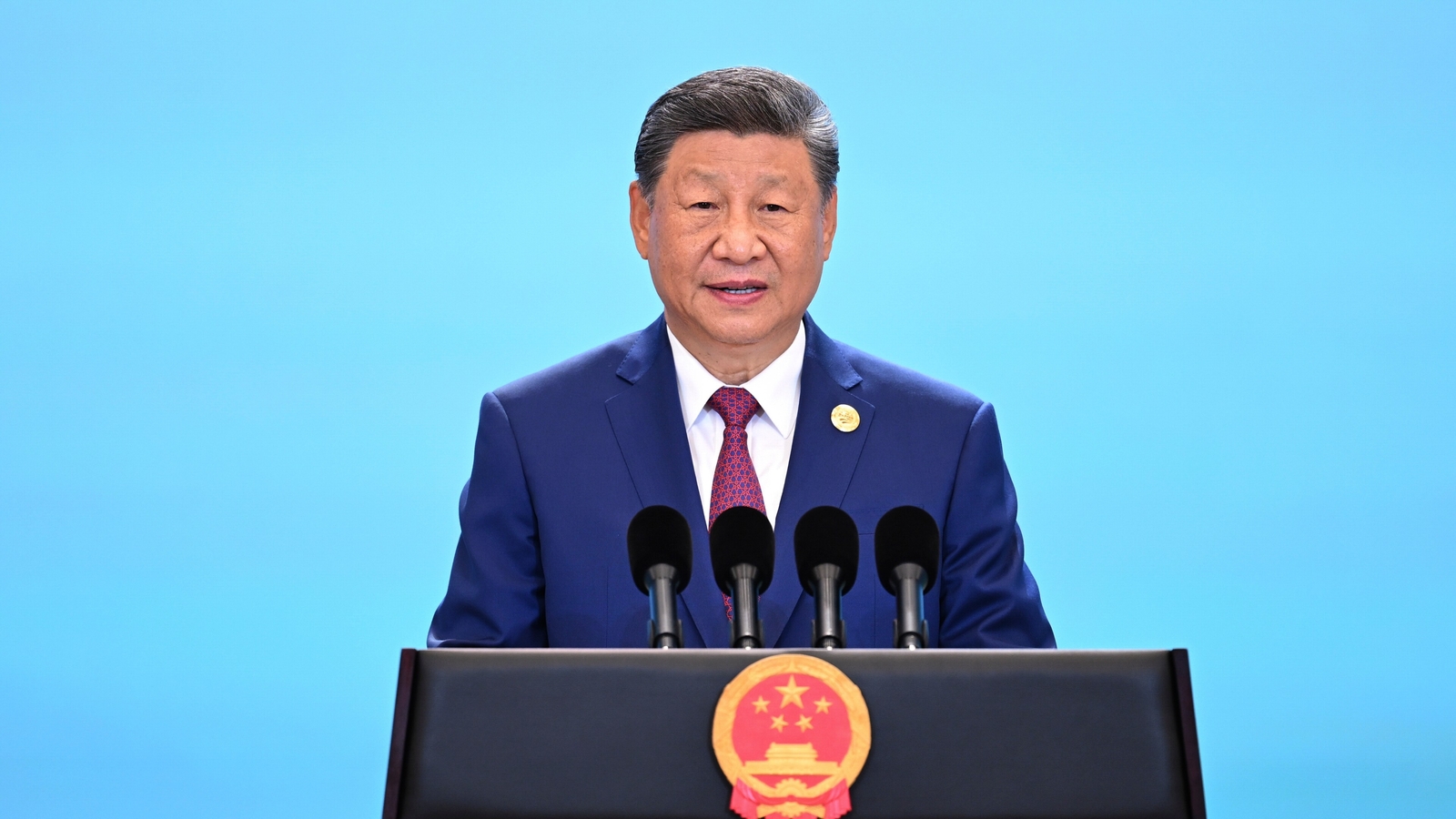

CHINA’S LEADER, Xi Jinping, sees difficult times ahead. At a conclave of the Communist Party’s most senior officials that ended on October 23rd he warned that over the next five years the task of ensuring China’s development while maintaining its security would become “much harder” amid a “notable rise in uncertainties and unforeseen factors”. Mr Xi’s meeting a week later in South Korea with President Donald Trump produced an uneasy truce in the two countries’ fight over trade. But it will not have eased Mr Xi’s biggest headache: America. The cure for Trumpian instability, as he sees it, is an alternative order that draws the rest of the world closer into China’s orbit.

Enter the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Not so long ago, some analysts wondered whether China might wind down this colossal infrastructure-building scheme, to which most of the 130 or so poor or developing countries collectively known as the global south have signed up. Mr Xi launched the scheme in 2013, aiming to boost growth and trade by building ports, railways, power plants and so on (and to land big deals for Chinese state firms, which got many of the contracts). The BRI was soon beset by claims that it was crippling countries with debt and damaging the environment. China began scaling back its loans. Yet though BRI activity ebbed during the pandemic, it has picked up sharply since 2023, reaching record levels. It is also helping to stimulate trade between China and the global south, expanding markets for Chinese goods that Mr Trump’s tariffs are pricing out of America.

First, look at the trade numbers. America is still the single biggest destination for Chinese exports of goods. Yet its share of China’s shipments has fallen sharply since trade tensions soared during Mr Trump’s first term as president, from nearly 20% in the first nine months of 2018 to less than 12% in the same period this year. The global south is taking up the slack. Year-on-year exports to ten members of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) grew by 15% in September, as they did to countries in Latin America. China’s exports to Africa jumped by nearly 57%. According to S&P Global, the global south took 44% of China’s exports in 2024, up from 35% in 2015. The financial-data firm reckons this group of countries also accounts for more than half of China’s global trade surplus. (America’s share of the surplus is 36%.)

Then consider BRI activities. These often involve projects that encourage trade. A Chinese factory built in a foreign country, for example, may rely on components or machinery shipped from China. It can thrive in local markets, or sometimes even in America’s by making goods appear to originate from a country other than China and thus evading China-related tariffs. In 2023, the first full year after China abandoned its long “zero-covid” policy, the total value of BRI investments and construction contracts was $92.4bn, according to a report by Christoph Nedopil of Griffith University in Australia in collaboration with the Green Finance and Development Centre at Fudan University in Shanghai (the report counts any Chinese state or private investment, as well as construction contracts, in countries that have joined the scheme as BRI “engagement”—China does not publish an official list of BRI projects). This was still below pre-covid levels, but a big rebound from the pandemic era (up from $74.5bn in 2022). In 2024 and 2025, BRI engagement surged. The rise of 30% in 2024, to nearly $122bn, was the largest increase in a single year in the history of the scheme. In the first half of this year the record was broken again, with more than $123bn of engagement, nearly double the same period in 2024, Mr Nedopil calculated.

In 2021, responding to widespread misgivings about the BRI, Mr Xi declared that it would shift to a new “small but beautiful” approach: less splurging on concrete-consuming infrastructure, and more spending on projects relating to health care, green energy, telecommunications and more; there would be no new Chinese investment abroad in coal-fired power. Yet in the past couple of years some BRI deals have been anything but small or beautiful. Of $39bn of BRI money directed to Africa in the first half of this year, a single deal accounted for nearly half: a $20bn contract awarded to a Chinese state firm for building oil and gas facilities in Nigeria. By value, fossil fuels now dominate in BRI-related energy projects. Another large slice has involved construction deals in Kazakhstan worth nearly $20bn involving copper and aluminium production.

Such megadeals involving state-owned companies mask another, more welcome trend, however: a surge in BRI activity, often involving non-state firms, in just the kinds of business that Mr Xi promised to encourage. Last year their overseas investments in solar, wind and waste-fuelled power amounted to $11.8bn. This 24% rise made it the greenest year in the BRI’s history, according to Mr Nedopil. Chinese firms poured in another $9.7bn in the first half of this year.

All this is not just a fillip for Chinese firms facing turbulence from Mr Trump’s tariffs. As Mr Xi sees it, the BRI pays geopolitical dividends too. Since 2013 it has involved more than $1.3trn of Chinese investments and contracts in 150 countries. China hopes that this money will encourage countries to back it in multinational forums, starting with the UN. For instance, 70-odd countries have already adopted language promoted by China that declares that “all efforts” should be made to achieve unification with Taiwan—implying that military force is acceptable. Most of these countries are signed up to the BRI.

There are also risks for China. Just as rich countries worry about the harm to their industries caused by a flood of cheap goods from China, so members of the global south have misgivings too. Many BRI countries are seeing their trade deficits with China widen. Protectionist mutterings are growing louder in both Africa and South-East Asia. Reckless Chinese lending in earlier years leaves a sting, too. A report in May by the Lowy Institute, a think-tank in Sydney, said China had “transitioned from capital provider to net financial drain” on developing-country budgets, as debt-servicing costs on belt-and-road projects in the 2010s now “far outstrip new loan disbursements”. The institute warned that these repayments could mean rising vulnerability to debt in many countries, especially in Africa. Key spending priorities like health, education, reducing poverty and adapting to climate change all risk being crowded out.

Yet China knows that with these countries it has a captive audience. Some may quietly grumble about trade imbalances or debt, but the technology and construction skills offered by China are often hard to find elsewhere. China hopes such countries see little choice other than to support it in its desire to be the architect of an alternative world order. As a Communist Party journal recently put it, the BRI will help create “a new paradigm of global governance”. In a Trump-troubled world, Mr Xi sees opportunities still.