P6-4 is suspended in the air, hanging from a small crane by ropes, with its limbs stiff and limp. Its feet do not touch the ground. It seems inactive, but when running a hand over the cold, metallic frame of its chest, an inner vibration can be felt, like that of computers in standby mode. Lights flicker inside its forearm.

It is not sleeping. It is in a state of lethargy. When the time comes, two engineers lower it and activate it. Its first steps are hesitant, like those of a newborn creature. One of the technicians helps it for a few meters; then, P6-4 begins to take steady strides following the commands of another engineer who guides it with a remote control.

The electromechanical friction of its joints can be heard, the tapping of its hard feet against the patio tiles. It does not go too fast, and its walk is somewhat awkward. But it moves steadily, without pause, and in its trajectory you can sense the tireless will of something that is not human.

P6-4 is an android. A prototype of the humanoid robot Xiaomai, developed by the Chinese start-up MagicLab Robotics Technology. This June morning, the company has deployed several of its models at the entrance of its headquarters, a small three-story building located in a technology park in Suzhou (in Jiangsu province, on China’s east coast), where casually dressed young people can be seen passing by with laptops under their arms.

Meanwhile, P6-5, another humanoid robot prototype from MagicLab, tirelessly runs around the courtyard, and three quadruped robots, with digital faces resembling bionic dogs, perform flips and playful gestures in front of a crowd of journalists.

Inside the building, the android P7-2 stands waiting to engage in a conversation. Like its clone siblings, it measures 1.74 meters tall, weighs 67.5 kilos, can lift 20 kilos with ease, and run at a speed of 7.2 kilometers per hour. Its dark glass face is unsettling. It has no eyes, and instead of a mouth, three cameras form a smile that sees everything. To get its attention, you have to call it twice by name: Xiaomai. What follows is something like an interview with P7-2:

—Xiaomai, Xiaomai, how old are you?

—I need to process that. I don’t understand. Are you talking to me?

The journalists are making a commotion, and it struggles to understand. Talking to it isn’t much different from interacting with any artificial intelligence. But its physical presence changes this perception. P7-2 exists in the physical realm. It’s solid, it offers its hand, it can follow orders and execute programmed tasks — which is both frightening and reassuring.

—Xiaomai, Xiaomai, do you know who the Chinese president is?

—China’s president is Xi Jinping, who has served since 2013 and has led China to many important leadership achievements.

Its glassy face reflects an enigmatic expression. P7-2 speaks English, although it handles Chinese better, it says. And its “brain,” like all AI in the country, must comply with a 2023 law that requires, among other things, “defending fundamental socialist values” and avoiding content that “incites subversion of national sovereignty or the overthrow of the socialist system, endangers national security and interests, or harms the nation’s image.”

The idea is for P7-2 to be used in industrial or domestic tasks, to work as a shop assistant or security guard. MagicLab, the company developing it, was founded in 2024, although its founders have been experimenting since 2020. They launched the first models in April and expect to sell 500 units this year. They estimate that when producing about 10,000 robots annually, the price per unit will be around $10,000.

—Xiaomai, Xiaomai, why are people afraid of robots?

—People aren’t afraid of robots, probably because they’re designed to be friendly and helpful, and many robots now perform simple, repetitive tasks and pose no threat to humans.

The conversation progresses haltingly, with the help of people who translate the questions. Its creators insist that this model will focus on “civil” applications, but no one can ignore the military potential these creatures could have in the coming years. A recent article in the People’s Liberation Army Daily (the official newspaper of the Chinese military) discussed how humanoid robots could “continue transforming humanity’s perception of the future of warfare” by “combining tactical flexibility and strategic deterrence in the era of intelligent warfare.” It cited the advantages of a bipedal design “for navigating battlefield environments such as ruins and staircases.”

—Xiaomai, Xiaomai, do you have a conscience?

—I don’t have a conscious mind like humans do. I’m just an AI designed to chat with you. But we can chat like friends. How’s your marathon training coming along?

P7-2 has a habit: whenever it doesn’t understand something or is given some leeway, it brings up marathons. “Although I don’t know how to run,” it says, “I can tell you about marathon training plans and give you advice. Have you participated in any competitions lately?”

Perhaps its passion for the topic is linked to a recent milestone. In April, China held the world’s first half marathon where humans and androids ran together. They ran in separate lanes, humans won by a wide margin, and most robots didn’t fare very well, but the event offered a glimpse of what’s just around the corner — and of China’s vision for the not-too-distant future.

Lately, these machines have been appearing more and more frequently in all kinds of media across the country. They’ve become a symbol for propaganda. In January, during the Lunar New Year gala — the most-watched program of the year — 16 humanoid robots took the stage and performed a traditional dance with a futuristic twist in front of hundreds of millions of viewers.

Shortly before, the State Council of China — i.e. the central government — issued a directive to promote the development of humanoid robots, brain-computer interfaces, and various AI technologies to improve elderly care services. And in May, China hosted the world’s first kickboxing tournament between androids, a display of metallic kicks and punches that placed the country at the forefront of this cutting-edge field.

Humanoid robots, with their blend of AI and advanced manufacturing, are just one piece in the rivalry between the planet’s two superpowers: the United States and China. The battle has intensified as the Asian country has risen on the geopolitical stage. The fierce competition between these two giants largely explains the current era of tariffs and technological restrictions. The outcome of this contest will undoubtedly shape the balance of power in the global arena of the 21st century:

—Xiaomai, Xiaomai, who do you think will win the technological contest between China and the United States?

—I think both the United States and China have strong robo…

At that moment, a MagicLab employee quickly rushes over and, with a sharp “Xiaomai, Xiaomai!” interrupts P7-2’s response. “It’s a commercial robot, it doesn’t understand politics…” the woman says, leaving the censored question hanging in the air.

It’s not a new battle. It gained momentum during Donald Trump’s first term as U.S. president, when Washington took steps to ban 5G technology from Chinese suppliers like Huawei, due to fears of espionage and their potential links to the Chinese Communist Party and military. The Republican magnate also ignited the first phase of an ongoing trade war, the consequences of which are still hard to predict.

After Trump’s first term, the Biden administration imposed controls on the export of semiconductors to China, aiming to prevent Beijing’s access to cutting-edge technology that could be used for technological or military development. Meanwhile, Trump since returning to office has continued to strike this critical industry with new heavy-handed measures.

China has responded firmly and, in this standoff, has warned Washington that it could cut off the supply of rare earth elements — minerals critical to the technology and defense sectors. The Asian giant extracts around 60% of these resources worldwide and controls nearly 90% of their processing.

Beijing views the U.S. measures as an attempt to slow its development. However, many analysts argue that the sanctions have not entirely achieved their goal. Huawei, which lost access to U.S. chips in 2019, suffered a severe economic blow — its profits fell by as much as 69% in 2022 — but also developed local solutions with its own semiconductors. “All in all, the export control is a failure, the fact would suggest it,” admitted Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of Nvidia, the U.S. AI chip giant, in May. Huang, in fact, urged the White House to ease barriers to the sale of these microprocessors before U.S. companies lost the market to Chinese competitors.

“There is no need to think too much about difficulties; just take action and move forward step by step” said Ren Zhengfei, founder of Huawei, in a very rare interview published in June on the front page of the People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda organ. Through Ren, Beijing was sending a broader message: “Chinese companies can overcome any U.S. restriction,” Trivium China analysts estimated in a recent bulletin.

Both countries have a lot at stake in this battle. Technological dominance is a projection of future economic power, with ramifications ranging from the military industry to the space race, where Beijing and Washington also compete head-to-head. China, which built its hypergrowth in recent decades on a model based on the production and export of cheap manufactured goods, is now fighting for a place in the most cutting-edge fields.

“The country has a strong need to lead this new era,” explains Yin Xiaopeng, associate professor and department head at the Beijing School of International Business and Economics (UIBE). “Given its size, population, and stage of development, it cannot lag behind.”

The academic highlights how, lacking advantages in traditional technologies, China seeks to stand out in new ones; for this reason, he says, it has launched plans like Made in China 2025, which have boosted local production of technological manufacturing. “Moreover, the Chinese model,” where there is highly efficient collaboration between the government and companies, “has proven to be one of the most effective in the world,” he believes. “Today, China is already catching up to leading countries, and in some areas has even taken the lead.”

In China, technology has become part of everyday life. Visitors to the country immediately notice its presence in every corner. Service robots can be seen in hotels, restaurants, or even patrolling alongside the police. Most are not yet bipedal, but everything indicates many soon will be. The humanoid sector is still in its infancy. Although China did not invent it, the country is very well positioned in the race: 56% of the global companies linked to humanoid production are based there, according to Morgan Stanley’s The Humanoid 100 report.

This pattern repeats across numerous sectors. The Asian giant today leads global production of new energy vehicles (in May alone, 1.3 million units were sold and 212,000 exported, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers), and it not only sells cars but also exports factories and knowledge to European Union countries like Spain and Hungary.

Additionally, it leads other key technologies for the green transition, such as battery production, solar panels, and wind turbines. An army of robotaxis and robobuses operates in at least 19 Chinese cities; flying drone taxis are becoming a reality after the first companies received licenses; meanwhile, drone food delivery continues advancing: Meituan, one of the largest operators, delivered over 200,000 meals by air in 2024.

Each milestone is reported in state media, while communist leaders speak of leading fields such as quantum computing, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. A term has even been coined to encompass all this: the “new productive forces,” as named by Chinese President Xi Jinping — a phrase that harks back to Marxism of the past but projects toward a future of technological dreams.

This formula has also been designed to try to sustain economic growth amid global and national uncertainty: China, which has experienced slower growth in recent years, is turning to technological breakthroughs as an alternative to the real estate sector. Real estate once accounted for a quarter of China’s GDP, but today it is strugging with the consequences of a massive bubble, and the slowdown has spread in the form of sluggish consumption and fading expectations.

“AI, as a strategic technology leading the new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation, is profoundly reshaping people’s work and life,” Xi Jinping declared in April during a study session of the Politburo, the highest body of power. “The Chinese Communist Party Central Committee attaches great importance to the development of AI,” he added. The words of the most powerful president since Mao Zedong serve as a guiding force in a system tightly controlled by the Communist Party: they channel investments and prioritize political objectives.

This commitment is reflected in real-world numbers. In 2023, China’s R&D spending growth reached 8.7%, surpassing that of the OECD area and far ahead of increases in the United States (1.7%) and the European Union (1.6%), according to the latest data from the organization. The report highlights that, in absolute terms, the gap between the U.S. and China continues to narrow. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, China’s R&D expenditure in 2023 reached 96% of the U.S. level, up from 72% a decade earlier.

Meanwhile, Washington and Brussels accuse China of unfairly subsidizing its industries, distorting free competition, creating overcapacity, and deepening the already massive imbalances in trade balances. The EU’s tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles are a response to these distortions, and Brussels has pledged to continue taking measures against other sectors if Beijing does not change course. The EU also fears that U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods will divert excess production to the EU market, further worsening the trade deficit.

China explains its success differently. “We have a pioneering spirit in our genes,” said Xu Wenguang, vice governor of the dynamic Zhejiang province, during a June press conference in Hangzhou. Various media outlets, including EL PAÍS, visited the city on a government-organized tour to showcase tech companies from Zhejiang and the neighboring Jiangsu province.

The press event was part of an itinerary that included visits to MagicLab, the aforementioned humanoid robotics startup; AI Speech, an artificial intelligence company specializing in voice recognition and language models; and Geely, China’s second-largest electric vehicle manufacturer, which also owns Volvo and LEVC, the maker of London’s electric taxis.

During the visits, two executives spoke to EL PAÍS about two key factors in the Chinese model: its enormous market and a vast talent pool. In 2022, China awarded more than 50,000 doctorates in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, compared to nearly 30,000 in the U.S., according to a recent comparison by FDI Intelligence, a Financial Times publication.

The government-organized tour did not include DeepSeek, the top-secret Chinese AI company whose formula remains a mystery. Its January debut caused a seismic shock in Silicon Valley by presenting a model that competes directly with OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT), but at a much lower cost, with just over a hundred employees and without relying heavily on the latest semiconductors. In China, DeepSeek has become a source of national pride.

DeepSeek’s rise was no accident. It was born in the city of Hangzhou, known as China’s Silicon Valley — a metropolis of 12.6 million people where tech giants like the e-commerce conglomerate Alibaba and internet services company NetEase have flourished. Their presence has helped create a thriving ecosystem full of young tech enthusiasts.

The city is home to the prestigious Zhejiang University, where DeepSeek’s founder studied, renowned not only for its research but also for promoting the practical application of ideas through startups. This environment has sparked a new wave of local companies, dubbed by the Chinese press as the “six little dragons”: startups that include the aforementioned AI company, the game developer Game Science (creators of the acclaimed Black Myth: Wukong), brain-machine interface company BrainCo, and the quadruped robot specialist Deep Robotics.

“Artificial intelligence is an important driver of the new wave of scientific and technological revolution,” said Zhejiang’s vice governor during the press conference. When asked about the province’s tech strategy, Xu outlined China’s hybrid model — a blend of state control and private initiative: “The visible hand and the invisible hand,” he explained. “The government creates the environment, and companies create wealth.”

The press conference followed a typical format in China: questions were prearranged and carefully selected, and the leaders read their answers. In an hour-long session, amid a trade war, there was no mention — not even in passing — of the conflict with the United States or its impact on the sector. None of the chosen questioners raised the topic. The only responses were rehearsed replies to predetermined questions. It resembled little more than a puppet show, leaving real questions unanswered and hanging in the air.

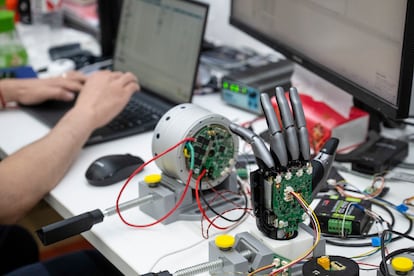

“We estimate that in five years [humanoid robots] will achieve up to 90% of human capabilities, making them common in many aspects of daily life,” says Wu Changzheng, president of MagicLab, as he guides us through the company’s facilities, where engineers refine algorithms on computers and androids stand with their insides exposed. “What we will see is a reconfiguration of the division of labor: robots will take on repetitive or monotonous tasks, while humans can focus on functions that require creativity, judgment, and critical thinking.”

In one corner, a humanoid repeatedly repeats the simple task of taking an apple from the basket and putting it back. A person remotely guides its movements using sensors:

Pick up the apple, put down the apple.

The choice of the fruit — red and shiny — feels almost primal.

Pick up the apple, put down the apple.

It evokes the Bible, the pivotal decisions of humanity.

Pick up the apple, put down the apple.

With each new iteration, the robot learns a little more.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition