Hong Kong

CNN

—

A summit of leaders from the BRICS group of major emerging economies kicks off in Brazil Sunday – but without the top leader of its most powerful member.

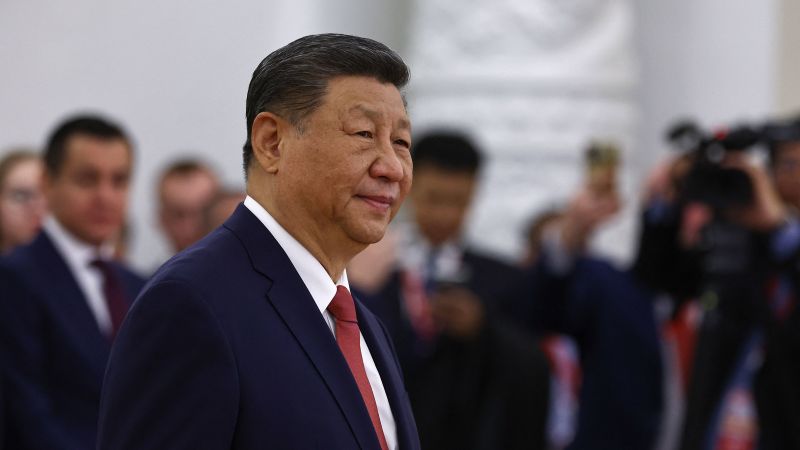

For the first time in more than one decade of rule, Chinese leader Xi Jinping – who has made BRICS a centerpiece of his push to reshape the global balance of power – will not attend the annual leaders’ gathering.

Xi’s absence from the two-day summit in Rio de Janeiro comes at a critical moment for BRICS, which owes its acronym to early members Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, and since 2024 has expanded to include Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Iran.

Some members are up against a July 9 deadline to negotiate US tariffs set to be imposed by US President Donald Trump, and all face the global economic uncertainty brought on by his upending of American trade relations – putting the club under more pressure show solidarity.

Xi’s absence means the Chinese leader is missing a key opportunity to showcase China as a stable alternative leader to the US. That’s an image Beijing has long looked to project to the Global South, and one recently elevated by Trump’s shift to an “America First” policy and the US decision last month to join Israel in bombing Iranian nuclear facilities.

But the Chinese leader’s decision not to attend – sending his No. 2 official Li Qiang instead – doesn’t mean Beijing has downgraded the significance it places on BRICS, observers say, or that it’s less important to Beijing’s bid to build out groups to counterbalance Western power.

“(BRICS) is part and parcel of Beijing’s effort to make sure it isn’t hemmed in by the US allies,” said Chong Ja Ian, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore.

But that pressure may have lessened with Trump in office, Chong added, referencing the US president’s shake-up of relations even with key partners, and for Xi, BRICS may just not be “his greatest priority” as he focuses on steering China’s domestic economy. Beijing may also have low expectations for major breakthroughs at this year’s summit, he said.

Xi is not the only head of state expected to be absent in Rio.

The Chinese leader’s closest ally in the group, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, will only attend via video link, for the same reason he also joined a 2023 BRICS gathering in South Africa remotely. Brazil, like South Africa, is a signatory to the International Criminal Court and so would be obligated to arrest Putin on a court charge alleging war crimes in Ukraine.

The absence of two global heavy hitters leaves ample limelight for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who will visit Brazil both for the summit and a state visit. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa is also expected to attend.

Some new club members have yet to announce their plans, though Indonesia’s Prabowo Subianto is expected in Rio after Southeast Asia’s largest economy officially joined BRICS earlier this year. BRICS partner countries, including some who aspire to join the group, will also send delegations. Uncertainty remains over whether Saudi Arabia has accepted an invitation to become a full member.

The sting of Xi’s absence for Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva may be blunted by the fact that the Chinese leader visited Brazil in November for the G20 summit and a state visit, when he and Lula inked a raft of cooperation agreements. The Brazilian leader also visited China in May, after attending a military parade in Moscow alongside Xi.

That recent diplomacy, low expectations for major breakthroughs at this year’s summit, and a heightened focus on domestic issues all likely factored into Xi’s decision to send Li, a trusted second-in-command, observers say.

China is facing steep economic challenges in the face of trade frictions with the US – and its leaders are busy charting a course for the five years ahead of a key political conclave expected this year.

In Rio, Li will likely be charged with advancing priorities like shoring up energy ties between Beijing and BRICS’ major oil-exporting members, while pushing for the expanded use of China’s offshore and digital currency for trade within the group, according to Brian Wong, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong, who added that Xi’s absence shouldn’t be interpreted as a snub to BRICS.

“Whether it be the Sino-Russian partnership or Beijing’s desire to project its purported leadership of the Global South, there is much in BRICS+ that resonates with Xi’s foreign policy worldview,” said Wong, using a term for the extended group.

Launched in 2009 as an economic coalition of Brazil, Russia, India and China before South Africa joined a year later, BRICS roughly positions itself as the Global South’s answer to the Group of Seven (G7) major developed economies.

It’s taken on greater significance as countries have increasingly pushed for a “multipolar world” where power is more distributed – and as Beijing and Moscow have looked to bolster their international clout alongside deepening tensions with the West.

But BRICS’ composition – a mix of countries with vastly different political and economic systems, and with occasional friction between each other – and its recent expansion have also drawn criticism as leaving the group too unwieldy to be effective.

The disparate group’s efforts to speak with one voice distinct from that of the West often become mired in opposing views. A statement last month expressed “grave concern” over the military strikes against BRICS member Iran, but stopped short of specifically naming the US or Israel, the two countries that carried out the strikes.

Nonetheless, the US will be watching how the countries talk about one issue that has typically united them: moving their trade and finance to national currencies – and away from the dollar. Such de-dollarization is particularly attractive to member countries such as Russia and Iran, which are heavily sanctioned by the US.

Earlier this year, among the goals of Brazil’s host term, Lula included “increasing payment options” to reduce “vulnerabilities and costs.” Russia last year pushed for the development of a unique cross-border payments system, when it hosted the club.

What’s unlikely to be on the negotiating table, however, is the lofty goal of a “BRICS currency” – an idea suggested by Lula in 2023 that has drawn ire from Trump even as other BRICS leaders have not signaled it’s a group priority.

The US president in January threatened to place “100% tariffs” on “seemingly hostile” BRICS countries if they supported a BRICS currency, or backed another currency to replace “the mighty U.S. Dollar.”

As countries convene in Rio, observers will be tracking how strident their leaders are in promoting the use of national currencies at a meeting of a group where China is the leading member, but US global economic clout still looms large.