In the 1990s, at China’s southern port of Xiamen, containers loaded onto ships were declared to customs as holding valuable export goods.

At a time when China was striving to expand global trade in a bid to join the World Trade Organization (WTO), Beijing provided substantial tax rebates for logistics companies, turning many into millionaires.

But there was a secret: many of the shipping containers were empty.

This fraud in China’s maritime industry saw exporters colluding with customs officials, exploiting state subsidies, and pocketing significant sums while creating an exaggerated narrative of the country’s booming exports.

It only came to light in the early 2000s with the exposure of a notorious smuggling case involving businessman Lai Changxing, whose extravagant lifestyle and corruption shocked the Chinese public.

Today, China produces 98 per cent of the world’s shipping containers, which have become a symbol of the economic superpower’s rise and fall.

After sending “made in China” products worldwide for nearly four decades, China’s bubble has been popped by the trade war with the United States and Xi’s crackdowns on key industries such as property and technology.

Those containers that drove China’s economy and global influence are now once again sitting empty, piled up at Chinese ports.

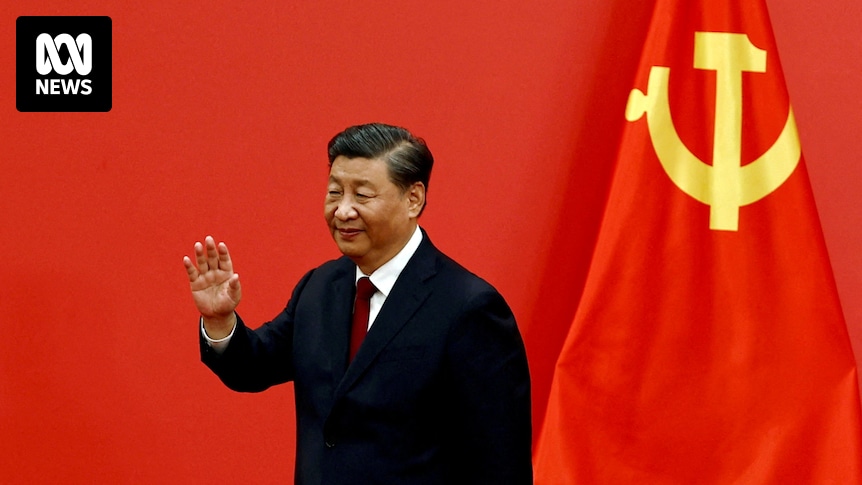

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang arrive for a ceremony on the eve of the 75th anniversary at Tiananmen Square. (Reuters: Florence Lo)

On the People’s Republic of China’s 75th birthday, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing its most significant political and economic turmoil since the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

As one of the longest-surviving authoritarian regimes in modern history, the CCP is grappling with challenges that expose deep vulnerabilities and threaten party chief Xi Jinping’s overarching vision known as “the Chinese dream”.

Economic decline threatens legitimacy

Eight of the world’s biggest ports are in China. (Reuters: China Daily)

In 1978, China’s first container ship sailed to Sydney and Melbourne, symbolising the country’s entry into global trade days before the economic reforms introduced by the then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

Deng’s first task was to address class divisions in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution.

This move was at the heart of the United Front — a strategy aimed at bringing together various social classes to drive national development.

It also tightened the party’s control over patriotic education, propaganda media, and the economy.

Since then, growth has been at the centre of the party’s propaganda.

The CCP today is striving to bring economic growth back on track, but the impact of China’s stimulus measures has been marginal at best.

In the lead-up to National Day, the People’s Bank of China freed up around $200 billion (nearly 1 trillion yuan) for lending, cutting interest rates from 1.7 per cent to 1.5 per cent and reducing mortgage rates and down payment requirements.

China has raised its famously low retirement age due to a huge pension deficit. (Reuters: Tingshu Wang)

Despite these measures, market sentiment and consumer confidence remain low.

In major cities like Shenzhen, 30 per cent of office buildings remain unleased, according to China’s state-owned media.

More than half of provincial governments failed to meet their fiscal revenue growth targets in the first seven months of the year — sending worrying signals about local governments’ financial health.

To address its significant pension deficit, Beijing raised China’s famous low retirement age, lifting it to 63 for men and 55 or 58 for women, depending on their occupation.

The CCP’s economic strategy is now colliding with shrinking demand for properties, partly driven by the impact of decades of the one-child policy.

Beijing’s crackdown on property developers has seen investors showing less confidence in the country’s property market. (Reuters: Tyrone Siu)

Middle-class parents who invested their life savings into properties as the market boomed for three decades are finding them worth much less after Xi’s crackdown on developers.

The younger generation — often only children with little interest in marrying or becoming parents themselves — stand to inherit at least one apartment each and show no signs of wanting to snap up all the vacant homes.

Rising living standards have always been a key plank of the party’s claim to legitimacy.

But as the economy slows, the CCP has to justify why it alone is the legitimate ruling power for the country’s 1.4 billion people.

Party-building faces challenges

Lai Changxing was escorted back to Beijing from Canada in 2011, after being charged for running a multi-billion-dollar smuggling operation. (Reuters: China Stringer Network)

The CCP’s claim that “only the Communist Party can save China” is also increasingly undermined.

In Lai’s case, port customs officials were bribed with a portion of the tax rebates. The military, particularly China’s navy, was also implicated in facilitating his operations.

Key political figures such as Xi and Jia Qinglin held senior roles in Fujian Province, where the city of Xiamen is, when Lai’s crime took place.

Both hailed from prestigious party families, with none of them stepping down for their accountability.

The empty containers in the 1990s are just one example showing the tricky relationship between the party’s top leadership and local officials.

In a system ruled by one man, local officials often inflate statistics to meet their KPIs, while simultaneously reaping lucrative rewards for doing nothing.

Corruption has become a widespread issue across almost every sector as the party’s membership swells to nearly 100 million people.

Of course, corruption doesn’t just happen in China, or a problem just the Chinese shipping industry has.

However, unchecked power could be more abusive than a democratic government, given its authoritarian nature.

Xi’s politburo has rolled out new stimulus measures to boost the country’s economy. (Reuters: Tingshu Wang)

Since the Tiananmen Square protests, it has remained a fundamental concern for Chinese citizens.

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, launched early in his tenure, was initially well-received by the public as an attempt to curb systemic graft and restore faith in the government.

However, with Xi’s unprecedented crackdown on freedom of speech and removal of inner-party checks and balances, the rule of law and some basic human rights remain unaddressed.

The younger generation’s desire to join the party is waning, with the growth of new members declining for a second year this July.

The crackdown on the wealthy elite, perceived by the public as an attempt to save the economy, is also expanding.

However, prestigious officials returning millions in bribes and facing expulsion appear to just erode the public’s faith in the leadership even more.

Youth unemployment is high, private enterprises are languishing under government control and the party’s long-standing economic success is tested by the aging and declining population.

Xi now faces mounting challenges that go beyond economic policy. He must address the growing social divide between the political elite and the people, tackle corruption more effectively, and ensure that the party’s grip on power is maintained without jeopardising the nation’s long-term future.

Whether this chapter of China’s history is remembered as part of a dream or a nightmare will depend on how Xi effectively navigates these turbulent waters.