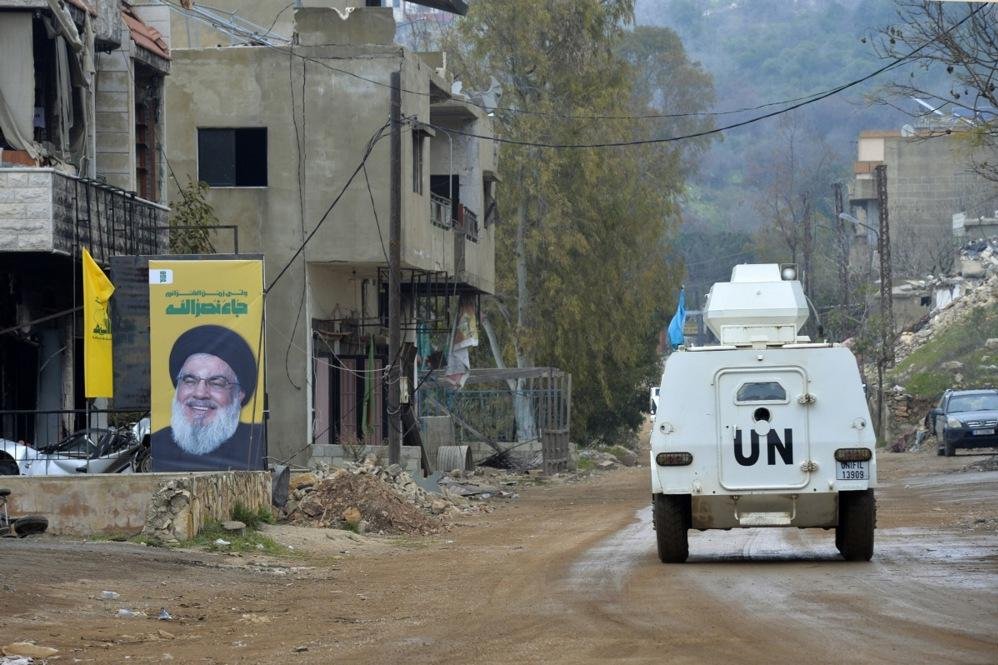

United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon soldiers patrol past the rubble of destroyed buildings in the village of Houla, southern Lebanon, earlier this month. A cease-fire agreement between Israel and Hezbollah went into effect in November 2024. Photo by Wael Hamzeh/EPA-EFE

BEIRUT, Lebanon, March 21 (UPI) — The deadly clashes that erupted this week in an area between Lebanon and Syria have brought historical border issues and smuggling problems to the forefront, along with fears of possible sectarian retribution spilling over from Syria, Lebanese political and military analysts said.

The cross-border clashes near the town of Al-Qasr in northeastern Lebanon — one of several key smuggling and supply routes long used by Hezbollah — were sparked by the killing of three soldiers of Syria’s new Army inside Lebanese territories.

Lebanon and Syria had different versions of what caused the killings and who was behind them.

While Lebanese reports indicated that the three were smugglers and were killed by armed members of a pro-Hezbollah clan after they crossed the border, Syrian authorities accused the Iran-backed militant group of kidnapping them from inside Syria and killing them.

Although Hezbollah, a key ally of ousted Syrian President Bashar Assad, denied any involvement, confrontations quickly broke out, killing at least 10 people and wounding 56, mostly Lebanese, during two days of artillery shelling.

The violence came to a halt after the Lebanese Army sent large military reinforcements to the border area and both countries agreed on a cease-fire.

Syria’s new leadership, led by Ahmad Sharaa, has vowed to combat the country’s Captagon trade that flourished under Assad and to destroy his drug empire. It also pledged to take control of the borders to prevent drug and weapons smuggling.

That was bad news for smugglers on both sides of the border and for Hezbollah, which not only lost a main ally with the collapse of Assad’s regime, but also its main supply routes, Riad Kahwaji, who heads the Dubai-based Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis, told UPI.

Kahwaji explained that Hezbollah created “very strong relations” with the Lebanese clans over the years because of “common interest: smuggling.”

After Assad’s ouster by Islamist rebels in December, Hezbollah was no longer able to receive weapons and other support that used to be channeled from Iran.

Kahwaji referred the tense situation along the borders as an attempt by Hezbollah and the smugglers to reach out to their former smuggling partners on the Syrian side “to restart the business.”

Hezbollah and other groups in Lebanon may have interests in maintaining these smuggling routes for funding and logistical purposes, said Yeghia Tashjian, regional researcher and analyst with the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut.

“Tensions over these routes, therefore, could spark clashes when one side seeks to clamp down on the trade while the other tries to protect it,” Tashjian told UPI, referring to Syrian authorities’ attempt to assert control over their borders.

Smuggling has been a main problem since the establishment of the border between Syria and Lebanon, which extends for approximately 230 miles from the east to the north, with no clear demarcation in many areas.

Illicit trade includes essential goods upon which that hundreds of families on both sides of the border rely for their livelihoods due to price differences in their respective markets. It also involves weapons, drugs, money laundering, smuggling currency and stolen cars.

The northern and eastern borders of Lebanon with Syria remain a contentious area due to historical disputes, natural geographic challenges and political factors.

Abdul Rahman Chehaitli, a retired major general and author of The Lebanese Land and Maritime Borders: A Historical, Geographical, and Political Study, said that after the French Mandate in 1920, both countries were delineated as separate entities, but there has been no formal border agreement between them.

Chehaitli said there were 37 “real estate-land ownership” disputes along the border, “which went out of the control of the Lebanese authorities” in the 1970’s in favor of Syria.

With the outbreak of the Syrian Revolution-turned into civil war in 2011, the border became “passageways” for Hezbollah, which engaged in the fighting in Syria to support the Assad regime, with mafias flourishing on both sides, he said.

With Hezbollah out of the equation after its war with Israel and the fall of its Syrian ally, only the smugglers are still active.

“The situation could become very dangerous if not contained,” Chehaitli told UPI, referring to the recent cross-border clashes and the possibility that the armed groups affiliated to the new Syrian authorities “are not aware or informed about their specific borders.”

Are smuggling and border control the only reasons behind the clashes? Did someone want to instigate such fights?

It’s not yet clear, but they could very well serve Hezbollah’s argument for the need to keep its arms to protect Lebanon and its minorities — both from Israel’s continued aggression and the possible emerging threats from the new Sunni-led rule in Syria.

Tashjian said that if sectarian conflicts in Syria escalate and lead to assaults on Hezbollah- or Shiite-populated villages on the border, the group might cite the worsening security situation as “a reason to preserve its military strength” to guarantee the safety of Shiites in Lebanon and Syria from sectarian attacks.

Earlier this month, more than 1,225 civilians, mostly Alawites, were killed in an outburst of sectarian retribution and killings after pro-Assad gunmen ambushed security forces of the transitional government and attacked government institutions in Syria’s coastal region — the heartland of the Alawite minority.

Fierce clashes also killed 231 people from the government security forces and 250 Alawite insurgent gunmen.

To Kahwaji, showing that the new leadership in Syria was “a threat to minorities'” and that the Shiites, who are allies of the Alawites, are also menaced fits Hezbollah’s claim to retain its arms.

“This could also be used as a pretext, an excuse to explain why they need to keep their arms — that it is not just Israel’s occupation [of some areas in south Lebanon],” he said.

Israel, which has greatly weakened Hezbollah during a destructive war that started in October 2023, is demanding the complete disarming of the militant group to withdraw from the southern areas and stop its continued air strikes.

The Lebanese Army, which was entrusted with taking control of the southern region in line with the Nov. 27 cease-fire that stopped the Hezbollah-Israel war, has also deployed in the clashes areas on the eastern border with Syria.

The Army emerged as the only force able to restore order on the border with Syria, as neither Hezbollah nor the inhabitants of those villages “have any other choice,” Chehaitli said.

He suggested that if the situation deteriorates in a way that threatens civil peace in Lebanon, it could bring the “old demand for deploying international forces to these frontiers back to the table.”

Kahwaji cautioned that the Lebanese Army could protect the borders, but cannot maintain peace there if people still carry arms and use them to instigate trouble.

To prevent the recurrence of such clashes and end the tension, Syria and Lebanon need to demarcate and closely monitor the border, block illegal routes and prevent a possible infiltration of radical fighters or “potential terrorists” from Syria, Tashjian said.