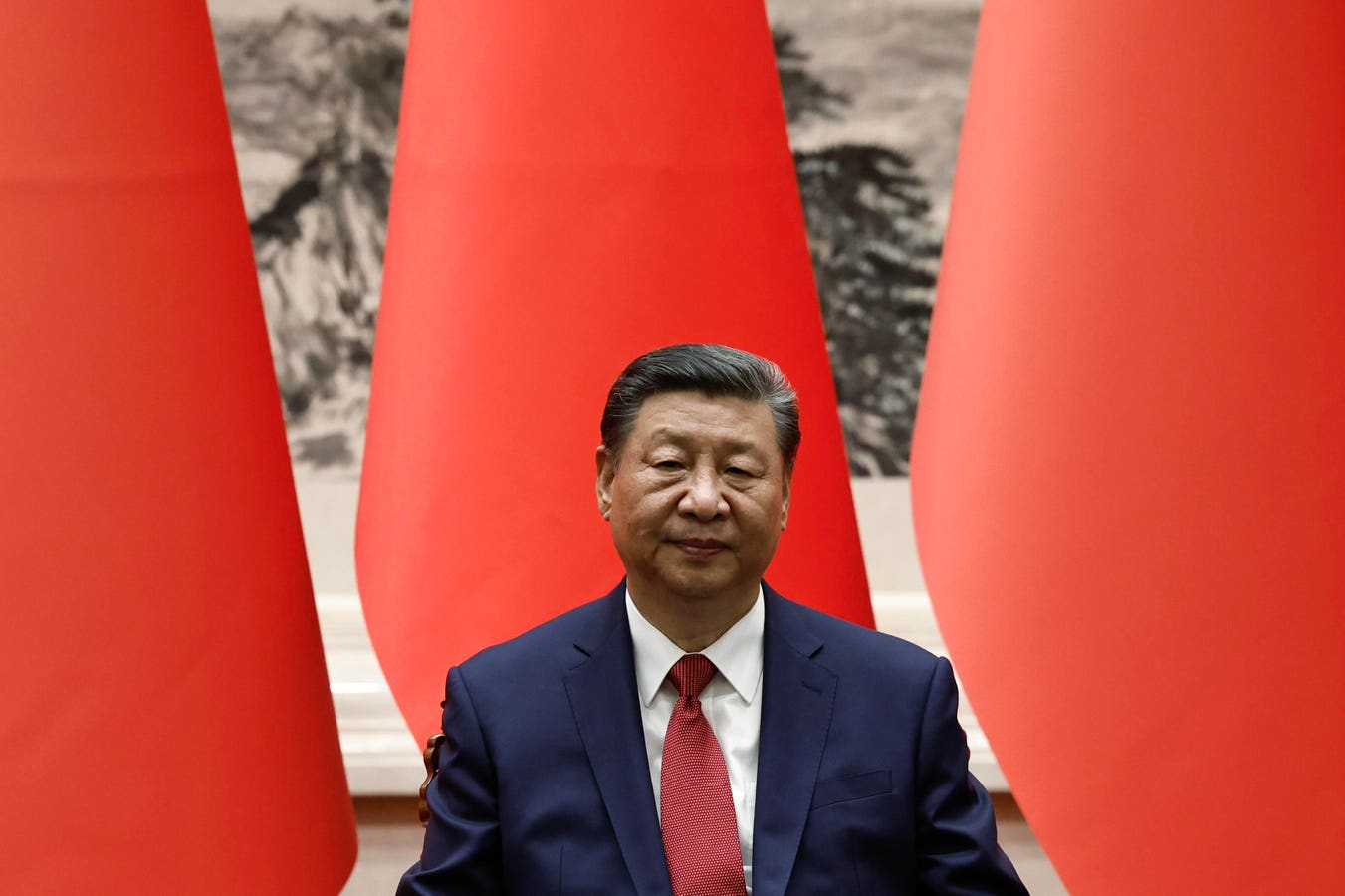

Chinese President Xi Jinping

Tingshu Wang – Pool/Getty Images

Few world leaders will be happier to see the back of 2024 than China’s Xi Jinping.

To say this year hasn’t gone well for Asia’s biggest economy is an understatement of historic proportions. The economy is limping out of 2024, hobbled by a deepening property crisis, deflationary headwinds, a shaky stock market and increased protest activity.

And that’s even before Donald Trump returning to the White House to unleash the mother of all trade wars.

Yet 2025 will pose its own challenges to Xi’s embattled Communist Party. Not least of which is a historical bookend as the 10-year mark of Xi’s “Made in China 2025” extravaganza approaches. It’s one sure to draw loads of report-card analyses that Beijing might not particularly enjoy.

Back in 2015, Xi was a few years into his stint as China’s longest-serving leader. He took power in late 2012 pledging to let market forces play a “decisive” role in Beijing decision making.

A big step in that direction came in 2015, when Xi plotted a course to 2025. The plan was to move an economy powered by cheap exports and low wages upmarket into high tech niche sectors. It meant dominating the future of semiconductors, renewable energy, electric vehicles, aerospace, biotechnology, artificial intelligence, robotics and green infrastructure.

This transition is vital to increasing competitiveness and reducing the risks of boom/bust cycles. Xi has made clear progress on most of these ambitions. A decade on, though, it’s hard to argue China is anywhere near where Xi planned.

Admittedly, some big challenges slowed things down. One was Shanghai’s stock crash in the summer of 2015. After the market lost a third of its value in three weeks, Team Xi seemed to lose confidence to push on with disruptive reforms.

Trump’s arrival in office 2017 shook the global economy in chaotic ways. His giant China-focused trade war dampened the party’s pain tolerance for supply-side upgrades. So did the Covid-19 pandemic.

Then there were the self-inflicted wounds. One of the most damaging came in late 2020 when Beijing clamped down on giant internet companies, starting with those founded by Jack Ma. As the crackdown intensified, investment banks began questioning if Xi’s exploits made China “uninvestable.”

As 2025 approaches, the biggest of the big money won’t be about to help assign grades to Xiconomics. And even the most generous reviewers will have to wonder why Xi hasn’t achieved much more in terms of transforming China’s economy.

The yawning gap between what was promised and where China finds itself comes down to Xi’s prioritizing security over change. What’s the point of being China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong if you can’t unleash a dose of Deng Xiaoping now and again?

The China of today is markedly less open and transparent than the one Xi took charge of 12 years ago. The media and internet climate, circa 2024, is moving in the wrong direction by every available metric. And rather than learn from Hong Kong’s celebrated capitalist model, Team Xi has sought to remake the once-thriving city in Beijing’s image.

At the same time, the dominance of inefficient and opaque state-owned enterprises — something else Xi promised to tackle — remains a clear and present danger to China’s ability to level playing fields.

On the bright side, it’s impressive to see Xi resist the urge to weaken the yuan. Given the deflationary forces building up in China, it’s surprised many that Beijing isn’t following Tokyo’s lead in pursuing a beggar-thy-neighbor exchange rate strategy.

One of Xi’s genuine reform wins has been internationalizing the yuan. Wisely, Xi has seen the ways in which the U.S. takes its reserve-currency status for granted. With Washington’s debt load topping $35 trillion, now does seem the time for an upstart currency to make its mark.

Given China’s scale, it’s an obvious candidate for a rival to the dollar. Policies in Beijing are a speed bump, of course. The lack of yuan convertibility is a problem, as is the absence of central bank autonomy.

Still, the inertia in the long run is away from the dollar. U.S. policies may be accelerating this dynamic by assuming China can’t present a credible challenge. Or that the BRICS nations — Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa — might create a robust dollar alternative.

But China finds itself in a tough place. Even tougher as narratives surrounding 2025 go awry.