Despite being banned in China, a dangerous pesticide that endangers farmworkers is flowing from Chinese manufacturers into the United States.

The U.S. imported between 40 million to 156 million pounds a year of paraquat, a toxic weed killer, over each of the past eight years, according to a recent report.

“The health and environmental harms of paraquat will be felt in U.S. communities for generations, while profits from paraquat sales overwhelmingly flow to Chinese companies,” researchers wrote.

Imports to the United States rose from just 11 million pounds in 2012, according to the report from advocacy organizations Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, Coming Clean and the Pesticide Action Network. The report was produced as part of a research series from the advocacy groups that’s examining the harm of pesticides.

While paraquat is prohibited from use on farms in China, continued imports to the United States are protected from trade barriers. Paraquat was recently put on a 37-page list of products that were exempt from tariffs President Donald Trump put on China.

In 2025, MLive in Michigan and AL.com in Alabama investigated the current use of paraquat, which is the subject of thousands of lawsuits across the country claiming the weed killer is linked to Parkinson’s.

Related: Thousands of U.S. farmers have Parkinson’s. They blame a deadly pesticide.

With evidence of its harms stacking up, its use is already banned in Europe, the United Kingdom and dozens of other countries all over the world. China banned it in 2021 to “safeguard people’s life, safety and health,” according to a government announcement.

However, from 2022 to 2024, about two-thirds of the paraquat imported into the U.S. came from two Chinese-owned companies, SinoChem Holdings Corp. and Red Sun Group, according to the report.

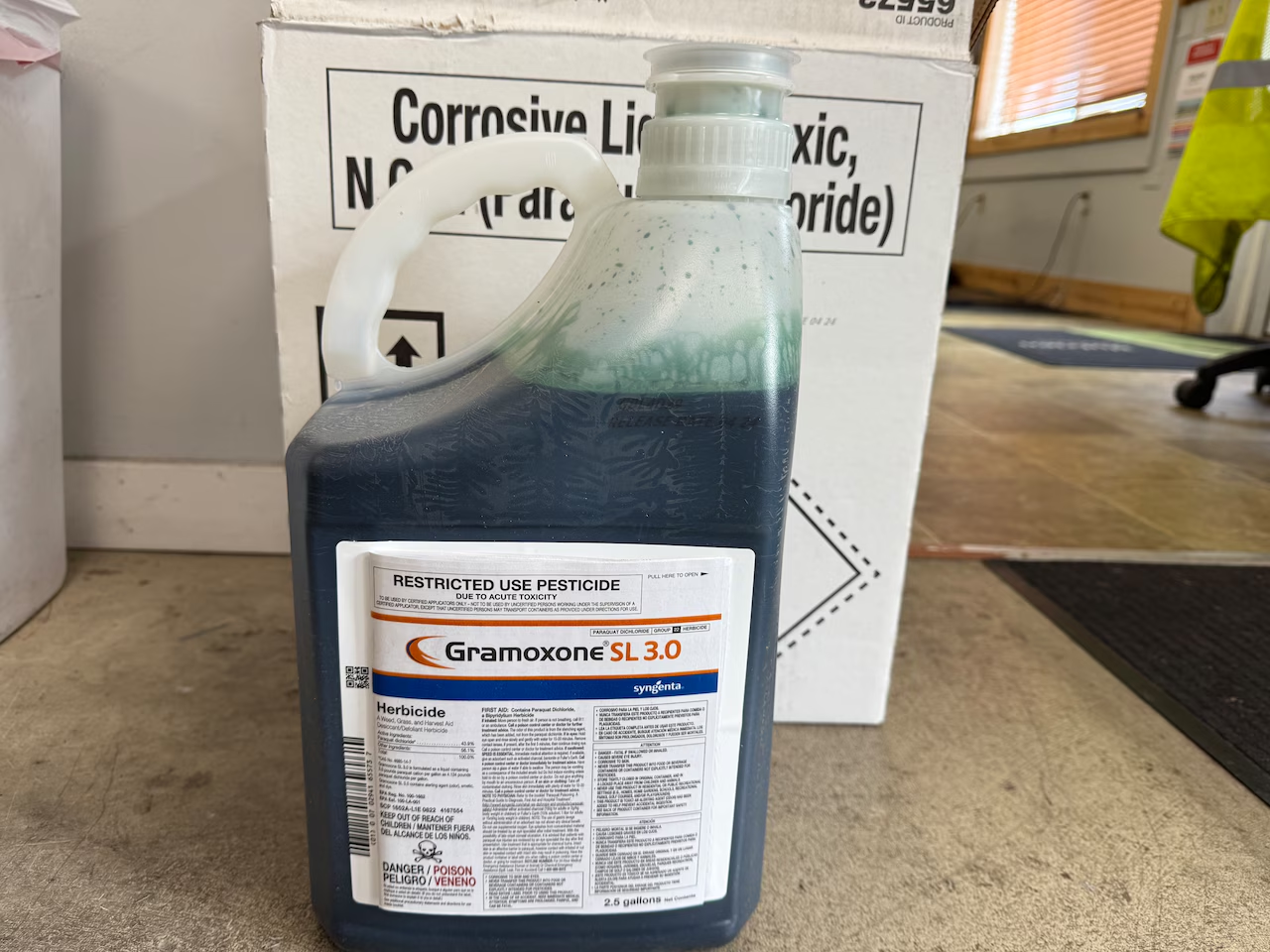

SinoChem has owned Syngenta, a chemical and seed company that manufactures paraquat under the brand name Gramoxone, since merging with its parent company ChemChina in 2020.

Paraquat is made at Syngenta’s large chemical factory in the United Kingdom, where use of the pesticide has also been prohibited for 18 years.

“The company is perfectly happy to make (paraquat), get all the economic benefits and then ship it for American workers to be exposed while banning it at home,” said Geoff Horsfield, policy director at the Environmental Working Group.

Paraquat is highly toxic — a sip is deadly and it can burn the skin — but one of the biggest concerns are the mounting allegations that low-level exposure over a long period of time could be linked to Parkinson’s disease. Thousands of U.S. farmers who are suffering from the neurological disorder have made this claim in court, but the cases are still pending.

Syngenta said that “despite decades of investigation and more than 1,200 epidemiological and laboratory studies of paraquat, no scientist or doctor has ever concluded in a peer-reviewed scientific analysis that paraquat causes Parkinson’s disease.”

“We have great sympathy for those suffering from the debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease,” a Syngenta spokesperson said in a statement for this report. “However, it is important to note that the scientific evidence simply does not support a causal link between paraquat and Parkinson’s disease, and that paraquat is safe when used as directed.”

China ties

SinoChem, which owns Syngenta, is one of 150,000 companies owned by the Chinese government, according to the U.S. Department of State.

“China profits directly from U.S. paraquat sales and is also a major purchaser of U.S. crops grown with paraquat,” the recent report from the advocacy organizations said.

Although many nations, including the U.S., have what are called state-owned enterprises, China has more than any other country. China’s state-owned businesses account for up to 40% of its gross domestic product and span the economy, the U.S. Department of State reports.

These are considered “de facto arms of the government” by the U.S. because they are “subject to government direction and interference.”

Although Syngenta, a subsidiary of SinoChem, is headquartered in Switzerland, its ties to the Chinese government have become a sticking point.

Two years ago, Arkansas ordered Syngenta to sell 160 acres of land, used for research, as lawmakers have scrutinized Chinese ownership of American farmland. China owns less than 1% of all foreign-owned farmland in the United States, Cato Institute research found.

Syngenta’s CEO Jeff Rowe, an Illinois farmer, has acknowledged these geopolitical issues, telling the Wall Street Journal he wants to build a bridge between the two countries

“Farmers know us and respect us,” he told the newspaper.

But despite ongoing U.S.-China tensions, the research report found paraquat continues to enter the country from Chinese companies, and it contends that this is effectively outsourcing “many of its associated health hazards.”

“Foreign-owned agrochemical companies are profiting while our essential farming communities suffer,” said Judy Robinson, executive director of Coming Clean, in a statement.

SinoChem, now a global agrochemical giant, posted $3.4 billion in profit last year.

How much paraquat is actually used?

Meanwhile, the use of paraquat in the U.S. is going up. But tracking just how much is not easy, according to the report.

The latest federal data, although out of date, shows paraquat use on American fields roughly doubled from 2012 to 2018.

Its use has increased, according to the report, because paraquat is a “stopgap solution to the superweed problem.” U.S. farmers can get stuck on a “pesticide treadmill,” using stronger pesticides to kill weeds that have become resistant to chemicals.

Paraquat is a burndown, meaning it’s used to quickly kill weeds or clear a field. Low levels of the chemical residue can linger on food crops, but it’s highly toxic through direct exposure for those spraying it or working near it.

There’s also a discrepancy between how much paraquat was sprayed and how much was imported, according to the report. In 2018, it’s estimated that up to 17 million pounds of paraquat were sprayed on fields compared to 95 million pounds imported.

This suggests that paraquat estimates are low, it’s being applied on nonagricultural land or the pesticide is being stored in warehouses, the report says. As of May 2025, U.S. farmers no longer must report to the federal government how much paraquat they’re using.

Farmworkers harmed

As paraquat continues to be widely used in American agriculture, advocates say farmworkers are being harmed the most.

“It really is this big stretch to get this product over here, get it out onto the fields, but at no point have we seen actual humane consideration for the workers,” said Claudia Lundberg from Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, an advocacy organization for women farmworkers.

Last year, Alianza Nacional de Campesinas set out to document what Lundberg calls a “silent problem” by collecting stories from migrant farmworkers who were exposed to paraquat and now have Parkinson’s disease.

One woman named Nora described how her whole family worked in the fields. Her cousin, a 55-year-old migrant farmworker, sprayed pesticides for roughly three decades on fields in New York, Florida and other states. About 13 years ago, he started having seizures and his hands shook uncontrollably.

He was then diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

“A big reason why paraquat has such a strong foothold is because the populations being affected the most are primarily migrant workers, sometimes undocumented and sometimes only here with the H-2A visa,” Lundberg said.

An ongoing study last updated in July 2025 of more than 50,000 pesticide applicators who worked with paraquat found they were 2.5 times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

More recent research studied 800 Parkinson’s patients in California’s Central Valley, a heavy agricultural region. It found there was a 91% increased risk of Parkinson’s disease for those living within 500 meters of where paraquat was sprayed.

In California, the only state that collects data on paraquat, about two-thirds of its use is concentrated in five Central Valley counties that are predominantly Latino and low-income communities, the report found.

“It really is the complete devaluation of human labor that goes into this for low prices,” Lundberg said.