To understand how effective U.S. sanctions on Russian oil could be, look no further than the already-sanctioned Arctic gas project central to Moscow’s export ambitions.

In multiple rounds of blacklisting, the Biden administration crippled the logistics, shipping and financing ecosystem around the natural-gas facility known as Arctic LNG 2, publicly aiming to leave it “dead in the water.” Yet since August, Russia has managed to send 11 tankers full of liquefied natural gas from the plant, ship-tracking data show.

On the receiving end: China’s port of Beihai, a city famed for its picturesque beaches that once served as a key stop along the ancient Maritime Silk Road. Now, it has emerged as a crucial node in the export of sanctioned gas from the Russian Arctic.

“It benefits both the Chinese economy and the Russian war machine,” said Alexander Gabuev, who is the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center and focuses on China-Russia relations. “China no longer feels the need to be overly concerned about the U.S. reaction.”

The U.S. and its allies have tried to cripple Russia’s energy industry since the invasion of Ukraine, but Moscow has found loopholes time and again. The Beihai gas route has become a key channel for that effort and a means to further deepen its ties with China.

The latest sanctions came last week when the Trump administration imposed new measures on Rosneft and Lukoil, Russia’s two largest oil exporters. On the same day, the Iris, a tanker the length of nearly three football fields, docked at Beihai in southern China carrying LNG from the sanctioned Russian gas facility.

Evading sanctions is a national priority as Russia tries to shore up its war chest, an especially urgent task this year as the country’s economy has begun to falter. For Beijing, it is as much an opportunity to snap up discounted Russian fuel as it is a signal of defiance in its trade war with the U.S., where China’s leverage over vital rare-earth exports has made it less concerned about American sanctions, observers say.

China and Russia show little effort to disguise the trade, with tankers carrying the sanctioned cargoes continuing to broadcast their positions through so-called AIS transponder signals.

Russia’s oil-and-gas exports, traditionally a source of cash and geopolitical heft for the Kremlin, have declined since it lost most of the European market. Although Moscow has been able to find new buyers for its oil, which is more easily transported by ship, replacing lost volumes of gas that used to flow through fixed gas pipelines has proved harder.

That made the $25 billion Arctic LNG 2 project essential for the Kremlin—and a natural target for Western sanctions. LNG plants work by cooling natural gas until it becomes a liquid, which shrinks its volume and makes it easier to transport by ship. The facility is central to Russia’s ambition to more than triple LNG exports in the coming years.

Building it meant transporting colossal concrete platforms called gravity-based structures, each exceeding 600,000 tons and among the heaviest objects ever moved. In December 2023, the first of three liquefaction plants, known in the industry as trains, was completed. Exports were supposed to begin in the first quarter of last year.

But then U.S. sanctions imposed on the project began to kick in. The U.S. has hit Russia’s fledgling LNG industry with several waves of sanctions since the war began. It has targeted operating companies for the Arctic LNG 2 project, storage vessels, shipping companies that it suspected were seeking to buy specialized carriers for the project and companies working on other facilities.

That gummed up financing and logistics for Arctic LNG 2 and stopped South Korean shipbuilders from delivering to the project. It also made it hard for Russia to build alternative vessels domestically. As a result, LNG output ground to a halt last year, leaving the facility mostly recirculating already produced gas.

That’s where Beihai comes in.

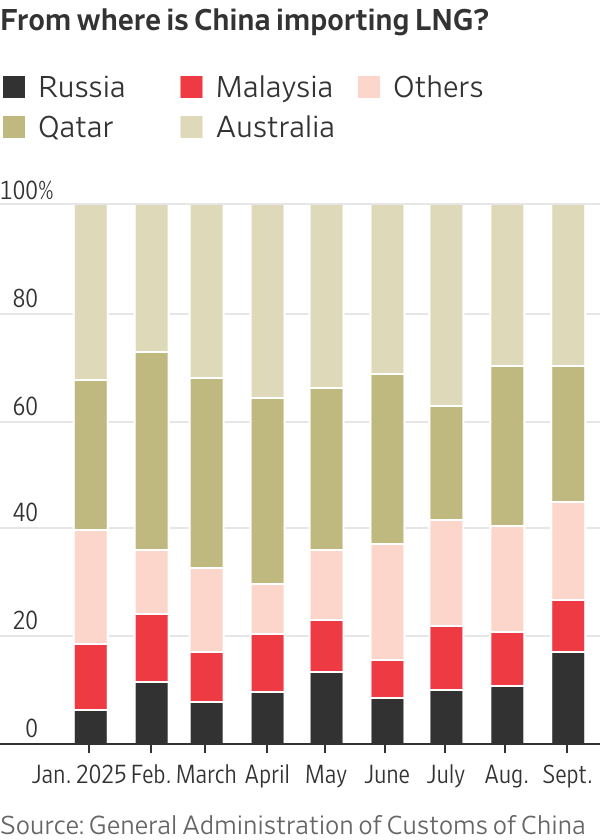

China became the world’s largest LNG importer in 2021, with cities, factories and power plants shifting away from coal and requiring ever more gas for heat and electricity. Imports climbed 7% in 2024 to 76 million tons, according to the country’s customs.

The Beihai LNG Terminal opened for business in April 2016 and has been continuously expanded since. It provides a steady supply of gas to China’s southern provinces including Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Guangdong and Fujian.

The Arctic LNG 2 gas is attractive for China because it comes at a discounted rate to other LNG in the region. But to buy it without risking secondary U.S. sanctions, China has made the port of Beihai its de facto entry point—no other LNG carrier has docked at Beihai since the terminal started accepting gas from Russia.

The operator of the terminal, state-owned China Oil & Gas Pipeline Network, mostly owns assets in China, with limited exposure to the dollar-based financial system, said Martin Senior, analyst at data provider Argus. That makes the port and its owner much less prone to the risk of secondary U.S. sanctions, he said.

The U.S. hasn’t sanctioned the facility, though the U.K. slapped sanctions on the terminal earlier this month, calling it an “entity involved in supporting the Russian energy sector.” At the time, China’s foreign ministry spokesman said that China “consistently opposed unilateral sanctions that lack a basis in international law.”

China also has provided the project with components, such as turbines, that Russia can no longer obtain from the West. To transport the gas, Russia has redeployed tankers from other sites and used some old ones, including from the so-called shadow fleet of vessels that rely on opaque ownership and shell companies, according to Jan-Eric Fähnrich, senior analyst at consulting firm Rystad Energy.

Challenges remain for Arctic LNG 2.

Russia still needs more tankers, and new vessels are unlikely to be delivered soon. Orders for key high-efficiency turbines were canceled under sanctions and the Chinese replacements are less powerful, cutting the export capacity of the facility, said Robert Songer, LNG markets analyst at data provider ICIS. Other buyers, meanwhile, are wary of the legal and logistical risks of buying gas from the project, he said.

Not so for Beijing—a reality that doesn’t bode well for the effectiveness of this week’s oil sanctions on Russia, according to Ronald Smith, founding partner of Texas-based Emerging Markets Oil and Gas Consulting Partners.

In the much smaller world of LNG trade, “demotivating buyers could be easier than doing so for buyers in the much larger oil market,” he said.

Write to Georgi Kantchev at georgi.kantchev@wsj.com and Rebecca Feng at rebecca.feng@wsj.com