This holds lessons for patient investors too: today’s billion-dollar write-off may be tomorrow’s trillion-dollar business

[SINGAPORE] In June 2009, a bespectacled senior vice-president at Microsoft launched Bing, the Redmond company’s answer to Google’s popular search engine.

His pitch was simple: search engines were broken, and Bing would fix that with an organised experience that delivered the right information effortlessly. Except it didn’t.

While Bing made some early inroads, it has hardly made a dent in Google’s search dominance.

Today, Google commands a 90 per cent market share, and Bing just 4 per cent – after burning through almost US$100 billion over 20 years, according to court documents.

You would think this spectacular failure would end a career. Instead, that same senior vice-president is now Microsoft’s chairman and chief executive officer, leading a US$3.7 trillion empire. His name: Satya Nadella.

Embracing the elephant in Redmond

Nadella doesn’t hide from Bing’s failure. In a rare moment of candour, he admitted that Google makes more money on Microsoft Windows than Microsoft does. Imagine that: Microsoft can only watch as its rival mints money off its own operating system.

BT in your inbox

Start and end each day with the latest news stories and analyses delivered straight to your inbox.

But don’t mistake candour for weakness. While Microsoft lost the search war, it is comfortably ahead in the cloud computing battle. Microsoft Azure’s US$75 billion in revenue over the past 12 months surpasses Google Cloud’s US$49 billion.

This cloud victory belongs to Nadella. Long before becoming CEO, he was the executive who pushed Microsoft into cloud computing, developing the infrastructure that would become Azure.

Yet, Nadella’s journey from Bing’s failure to cloud success isn’t unusual in the tech world. Many of today’s most prominent executives have massive failures on their resumes – it’s practically a rite of passage.

The fellowship of failure

Consider Amazon’s Ian Freed, who oversaw the Fire Phone disaster that cost the company US$170 million in write-offs.

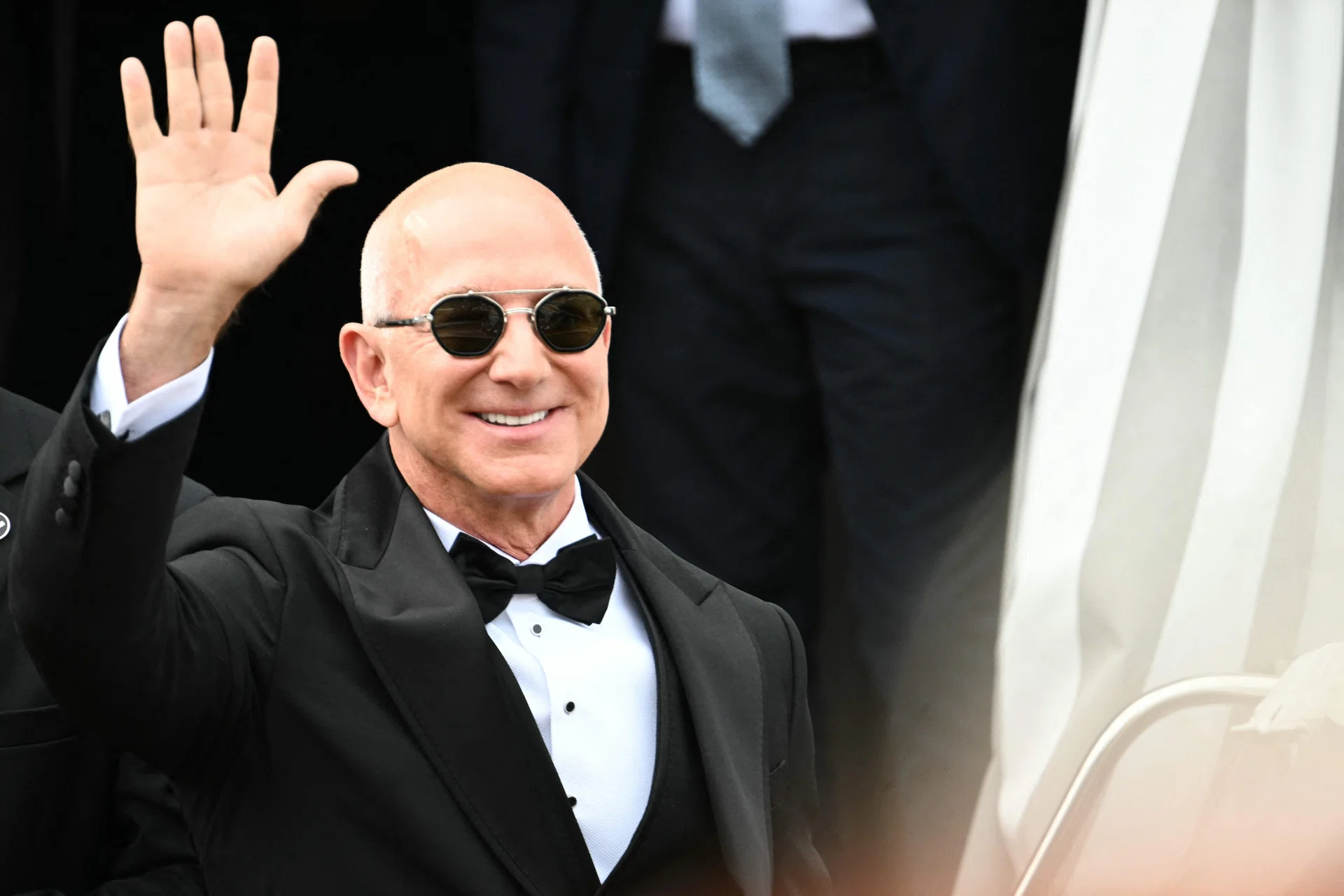

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’ response says it all. He pulled Freed aside with advice that captures tech’s relationship with failure: “You can’t, for one minute, feel bad about the Fire Phone. Promise me you won’t lose a minute of sleep.”

The lesson? In the tech world, your failure can be your most valuable credential – proof you’ve taken real risks, learnt hard lessons and survived to apply them.

Freed’s story proves this point. While developing the Fire Phone, Freed demonstrated a voice-recognition feature to Bezos that could play any song on command. Bezos was mesmerised, and asked Freed to build a voice-activated computer inspired by Star Trek.

The Fire Phone flopped, but its voice technology became the seed for Alexa and Amazon Echo. Today, there are more than 600 million Alexa-powered devices out in the world. The US$170 million failure has morphed into one of consumer tech’s biggest successes.

Here’s what most people miss. Echo’s success required multiple failures such as the Fire Phone. That’s why Bezos proudly says Amazon is the best place in the world to fail. His logic is compelling: “To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment.”

Here’s the rub. Most companies will agree with Bezos on the need to experiment, but few are willing to suffer the string of failed experiments necessary to get there.

Bezos, however, embraces the brutal math. Given a 10 per cent chance of a pay-off of 100 times, you should take that bet every time, he argues – even though you’ll be wrong nine times out of 10.

The 15-year overnight success

Here’s the tough part: success after a massive failure is only obvious in hindsight. Alphabet tells exactly this story. Ever since OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November 2022, Alphabet has found itself in an unfamiliar situation – playing second fiddle to OpenAI’s popular artificial intelligence (AI) assistant.

But with the recent launch of Gemini 2.5 Flash Image, Google is starting to look innovative again. The new image feature (code-named Nano Banana) attracted more than 10 million new users in a week, with over 200 million images edited.

Here’s what most people don’t realise: Nano Banana’s success was about 15 years in the making. The story begins with Google+, the company’s catastrophic attempt to challenge Facebook. Launched in 2011, Google+ burned through hundreds of millions before being shuttered in 2019.

But buried within that failed social network was a gem – Google Photos. When Google Photos became a standalone product in 2015, it brought along the image editing and organisation capabilities developed for Google+. Those capabilities – during its failed social network experiment – would give Google’s image AI the headstart it needed.

Fast forward to today, the technology that couldn’t save a social network now powers Google’s comeback in the AI race. Nano Banana’s overnight success took about 15 years of patient failure.

The irony of success

These stories – Microsoft’s Bing to Azure, Amazon’s Fire Phone to Echo, Google’s social network failure to AI success – share a common thread.

Yet most market leaders can’t replicate this pattern. They’re trapped by what the late Clayton Christensen called the “innovator’s dilemma”.

These organisations have spent years, even decades, perfecting their craft. Every process, metric, and incentive is designed to protect and grow the core business. But the brutal irony is that the same discipline becomes the barrier to their next breakthrough.

New innovations are starved of resources, unable to compete with a core business that’s already a profitable, well-oiled machine. Why risk experiments that will fail nine times out of 10 when the current model delivers reliable returns?

But if that’s the case, how do the likes of Amazon and Google break free from the downside of success? The answer may lie in skunkworks, a concept pioneered by Lockheed Martin in 1943. Today’s tech giants have adapted this model through their research labs – but not all labs are created equal.

Get smart: Success born out of failure

The successful research labs share a crucial trait – radical autonomy. Amazon’s Lab126 operates 1,350 kilometres from its Seattle headquarters – far from quarterly pressures and corporate bureaucracy. The results speak for themselves: Kindle, Fire tablets, Fire TV, Echo.

Elsewhere, Google’s X, the “Moonshot Factory”, has loftier goals. Its job is not to invent new Google products but to create the inventions that may form the next Google.

Graduates include Waymo (self-driving cars) and Google Brain, now part of Google DeepMind – the AI division responsible for Gemini and its latest Nano Banana.

The pattern is clear: breakthrough innovation requires separation from the core business. For investors, the lessons are:

- High-profile failures may signal opportunity, not disaster.

- Watch how executives handle failure. Do they admit mistakes openly like Nadella?

- Look for companies with “failure labs” – autonomous labs, experiment budgets that embrace Bezos’ brutal math of taking a bet that has a 10 per cent chance of a pay-off of 100 times.

Above all, patience is everything.

The stock market punishes failure in the short term. But for patient investors, today’s billion-dollar write-off could be tomorrow’s trillion-dollar business.

The writer owns shares of Alphabet, Meta Platforms, Microsoft and Amazon. He is co-founder of The Smart Investor, a website that aims to help people invest smartly by providing investor education, stock commentary and market coverage.