The world is experiencing a gigantic power struggle to shape a new global order. Donald Trump’s offensive to push his America First agenda, centered on the tariff war, is a particle accelerator in this context, one that is exposing the stark reality of international power relations. In it, the United States and China stand out as superpowers, vastly outstripping the others, many of whom are sending out signals of submission, while others are resisting—but from much lower power categories.

The United States has flexed its muscles in recent months by imposing sweeping tariffs across half the globe, demanding steep increases in military spending from highly dependent allies, bombing Iran with an operation no one else could carry out in that manner, and pushing two of its extraordinary technology companies (Nvidia and Microsoft) beyond the $4 trillion threshold in terms of market capitalization.

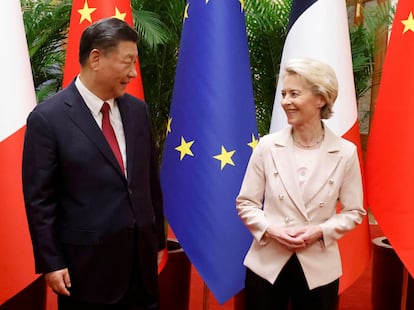

Faced with the impetus of the Trumpist offensive, China has demonstrated its own power with restrictions on exports of strategic raw materials that have sent shivers through global markets. Its resilience amid the storm was reflected last week in a significant upward revision of its growth outlook for this year—from 4% to 4.8%—according to the International Monetary Fund. The astonishing muscle of its industry, doped by unparalleled subsidies, brutally impacts its competitors. Technological achievements—such as the DeepSeek language model, launched just as Trump was being inaugurated—are increasingly eloquent. So is indifference to European requests—for example, to curb support for the Russian economy, without which the invasion of Ukraine could not continue at its current intensity.

The combination of military, technological, economic, productive, and political capabilities places these two countries in a strong position of preeminence. The others are exposed to dangerous risks.

“We are moving toward a world of much more evident realpolitik than to date, where the use of force will be much more central to international relations than it has been until now. It is the end of an order that was not always perfectly rules-based, but which had rules, international law, multilateralism, and international governance at its core,” says Manuel Muñiz, international rector of IE University and former Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the Spanish government (2020-2021). Force has always mattered, but its impact is now exacerbated in an unbridled world of total impunity.

Muñiz points to two factors converging to create this situation: “The hegemonic power that had built these rules and institutions, the United States, no longer wants to be constrained by them; on the other hand, we see the rise of some powers—primarily China, but others as well—that either do not want to be subject to some of these rules or want to establish their own.”

“In that context,” Muñiz continues, “the most obvious interpretation is that we’re heading toward a G-2 in global terms, an economic, technological, and military G-2 in which the relationship between these two countries is profoundly dialectical, in all the dimensions of collision that can arise. This is clearly the case in the economic and technological spheres. This is the case in the security and military spheres. This is the case in the normative and political system spheres. Therefore, I believe that what this constitutes is a structural and long-term collision between the United States and China that will shape international relations.”

Rafael Dezcallar, former Spanish ambassador to China (2018-2024) and former director general of Foreign Policy (2004-2008), agrees with this view. “Those two countries are the only ones with a global vision of what they want. They are, moreover, contradictory visions and in inevitable conflict,” says Dezcallar, author of The Rise of China. A Look at the Other Great Power.

Dezcallar summarizes the strengths of the two superpowers thus: “What will define the global development process is that China can profoundly influence the industrial development of countries with its handling of rare earths, at least for a while. And the United States currently has cutting-edge technology in the most important sectors and, of course, unquestionable global military superiority.”

The two countries’ approaches are different, with Trump’s rhetoric running riot, but Dezcallar urges us not to lose sight of the fact that “China has a very clear idea: it wants to change the international order.”

The technology index recently compiled by Harvard University’s Belfer Center points to a strong dominance of the two powers in key sectors such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, quantum computing, and semiconductors. This is where a core of strength lies. The United States maintains an advantage, but China is close behind, achieving a formidable connection between technological advancement and manufacturing capacity. Considered as a whole, Europe is not far behind, but the abstract sum made by the Belfer Center does not carry the same political impact in reality.

The same applies to military spending. The U.S. and China stand out far above the rest. Washington maintains a wide lead in terms of nominal spending, but when compared to purchasing power parity, Chinese investment now accounts for half of U.S. investment, according to data from the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Its shipyards produce ships at an astonishing rate.

The limited use of its weapons in real combat scenarios raises doubts about the effectiveness of its products. However, the recent clash between India and Pakistan, in which the former used French Raphael fighter jets and the latter used Chinese J-10s, yielded results that support this effectiveness, with the downing of at least one of the French-made aircraft. A Reuters investigation suggests that the feat was possible thanks to the highly effective PL-15 missiles mounted on the J-10 and the miscalculation of Indian forces, who did not believe it was capable of striking from the distance at which it did.

Here again, as in the previous section, the total military spending of European countries is considerable, but the reality is that they lack a true overall operational capacity, which is guaranteed only by NATO, with the U.S. as its hegemonic force. Again, the total is merely an arithmetic exercise, not a real deterrent.

Even when talking about economic weight, where the European Union still has a GDP equivalent to that of China and where the joint European project does represent an instrument with certain capacities for power projection, recent events show that absolute weight does not correspond to real power—because other attributes are lacking. The large internal market, its position as a major buyer of U.S. services, the management authority in the hands of the Commission: none of these theoretically valuable instruments prevented the EU’s submission to Washington in a disadvantageous trade pact.

The other relevant actors are at an abysmal distance.

Russia has a massive nuclear arsenal, a vast territory with all that this entails, and significant hydrocarbon and mineral resources. But it has a modest and dependent economy—comparable in size to Italy or Canada—an aging society, a political system based on a single man, and a high risk of chaotic transitions. The Kremlin would be unable to sustain its offensive against Ukraine if China decided to cut off the flow of trade that sustains it, especially with the supply of dual goods (for military and civilian use) that Russia is unable to produce.

India is advancing on a strong growth path and has the demographic, economic, cultural, and political attributes to be considered a powerhouse today, but there is no doubt that it is still a long way from the hegemonic duo. One example of this, among many others, is its extremely strong external dependence on weapons and other advanced technologies.

In Latin America, Brazil, led by Lula da Silva, is sending clear signals of its political will to resist, but its economic, technological, and military circumstances prevent it from becoming a truly relevant player on a global scale. The lack of regional integration prevents the subcontinent from projecting influence through cooperation.

“It’s an increasingly bipolar world, although it won’t be like the Cold War. There was military, nuclear, and ideological competition, but there wasn’t economic competition. The USSR wasn’t a rival to the United States in that sense. Today’s is a different kind of bipolarity, in which there is room for some actors, in some specific sectors, to also play a relevant role,” Dezcallar believes.

This is the current reality. But the outlook could change. Muñiz sees a G-4 as the central scenario in the medium to long term, a system in which the two current superpowers would be joined by “two real poles of power”: India and the EU.

In the first case, the economic and demographic potential is evident. “Of course, this is a question mark, because we’re talking about projections. But, barring a major political problem, the central scenario is that India will be an inevitable player,” says Muñiz, who points to a Goldman Sachs projection study according to which, by 2075, the U.S., China and India will have similar GDPs of around $50 trillion (and the eurozone around $30 trillion), with all others far behind. Muñiz believes that within two decades, India will be a powerhouse of enormous importance.

In the case of the EU, the question looms even more intensely, as it involves coordinating the political will of many states and not just ensuring the effectiveness of one state’s management. “Even so, my central belief remains that Europe will integrate, because the environment will generate pressure on European countries, and it will be so evident that the path to division is harmful to European citizens, that I believe we will take the necessary steps to integrate,” says Muñiz.

The position of the U.S. and China itself is not secure.

For the U.S., what is now a display of overwhelming power could turn into a wound. Many experts believe that tariffs—even if they generate some revenue and protect a manufacturing space—will be a problem for the U.S. economy. The distrust and resentment of its former allies appears likely to erode the solidity of a network of ties that facilitated America’s projection of hegemony. The culture war against universities and other repellent traits of the America First seriously question the U.S.’s ability to remain an attractive force for the world’s best minds. The situation is such that Ivo Daalder, former U.S. ambassador to NATO, believes Washington is losing the race with Beijing, according to an op-ed published in Politico.

At the same time, China faces serious problems. First, a complicated demographic curve. Central projections indicate that, without profound changes, by the end of the century China will have fewer than 800 million inhabitants, compared to India’s 1.5 billion. This is a troubling rate of shrinkage. The extremely strong export-led manufacturing push doesn’t mean its economy isn’t facing domestic problems. The resort to key export-restrictive measures, while simultaneously flexing its muscles, is a powerful wake-up call for others, who will seek to reduce dependencies they naively incurred.

The struggle to shape the world order is underway. In the medium term, the outlook may change, but in the present and short term, the realization of U.S. and Chinese supremacy is stark and crystal clear.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition