Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and/or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 19th April 2025, 03:23 pm

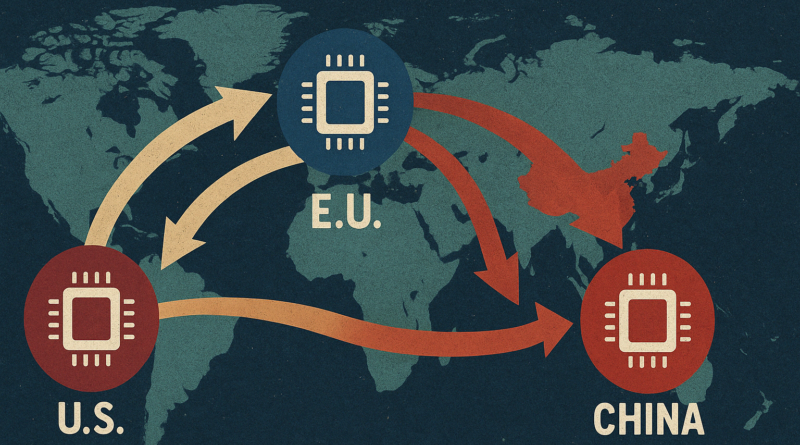

Imagine a future scenario unfolding through 2025, where global semiconductor alliances—long carefully coordinated by the United States—begin to fracture dramatically. This speculative future doesn’t hinge on new technological breakthroughs or sudden security crises, but instead arises from political and economic miscalculations by an increasingly isolated and confrontational United States.

The second Trump presidency has been marked by the return and aggressive escalation of tariffs—not just on traditional adversaries, but on European, Japanese, and South Korean allies as well. The global technological order, previously delicately balanced, could begin to unravel quickly.

To grasp the potential significance of this speculative scenario, first reflect on how we might have arrived at such a crisis point. In earlier years, particularly under Biden, the United States pursued a policy termed by some as “small yard, high fence,” where semiconductor restrictions targeted specific, advanced technologies critical to China’s growth ambitions. The centerpiece of these restrictions was preventing Chinese access to advanced lithography machines, especially ASML’s EUV systems, which are essential for producing the most sophisticated chips at nodes smaller than 7 nanometers.

Complementing these equipment restrictions, the U.S. implemented stringent software export controls targeting essential electronic design automation (EDA) tools from American firms such as Synopsys, Cadence, and Mentor Graphics. These tools, critical for designing and validating cutting-edge chips, became inaccessible to Chinese semiconductor companies, severely limiting their capacity to innovate or scale advanced-node manufacturing.

Additionally, import restrictions under the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) significantly curtailed China’s ability to procure advanced semiconductors fabricated with U.S.-origin technology, even when manufactured in third countries. Together, these software and import controls compounded the limitations imposed by equipment restrictions, effectively hampering China’s ambition to independently produce chips at the most advanced levels of technological sophistication.This strategy, while causing friction, maintained a fragile international consensus, with European and Asian partners generally cooperating, albeit reluctantly.

By 2024, China had already made substantial progress scaling up domestic production of semiconductors at nodes larger than 10 nanometers. These mature-node chips are essential building blocks for a wide array of critical sectors, including automotive electronics, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, industrial automation equipment, consumer appliances, and 5G telecommunications infrastructure. Chinese firms, notably SMIC, had also begun innovating significantly in advanced packaging techniques, particularly chip stacking technologies, enabling greater performance and capabilities even with less advanced manufacturing processes.

Semiconductors at the 7-nanometer and 5-nanometer nodes underpin critical advances in both civilian and military technology, playing a central role in the latest generation of flagship smartphones, advanced data centers, artificial intelligence hardware, autonomous vehicles, and sophisticated military systems. These highly miniaturized, energy-efficient chips are vital for defense applications such as advanced radar systems, precision-guided weaponry, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), stealth aircraft avionics, electronic warfare platforms, and next-generation secure communication networks.

By 2024, China had succeeded in manufacturing limited volumes of domestically produced 7-nanometer chips, but these remained scarce, costly, and hampered by low yields and significant manufacturing hurdles. Consequently, despite this strategic breakthrough, China’s capability to scale production of these advanced chips fell significantly short of leading global manufacturers like TSMC and Samsung, and production of 5-nanometer chips remained effectively beyond reach, further complicating China’s ambitions to achieve full semiconductor self-sufficiency.

Huawei, responding to the intense U.S. sanctions, successfully delivered its Mate 60 smartphone in late 2023, a landmark achievement featuring an almost entirely U.S.-component-free design. This included an advanced, domestically produced 7-nanometer chip, and the smartphone ran entirely on Huawei’s HarmonyOS operating system, which had already overtaken Apple’s iOS within China, establishing a robust, fully Chinese digital ecosystem independent of American technology.

In 2025, however, American domestic politics have turned increasingly inward and illiberal, while foreign policy grows more aggressively unilateral, zero-sum and abrasive. The return of Trump to power has been accompanied by unprecedented tariffs—broad, punitive measures targeting traditional allies alongside adversaries. European, Japanese, and Korean companies, deeply dependent on open trade and reliable market conditions, see these tariffs as a fundamental breach of trust. Such moves are likely driving traditional U.S. allies toward reconsidering their commitments to American technological containment efforts against China.

In Europe, ASML would stand at the center of this hypothetical pivot. In this scenario, the Dutch government, reacting to the new American stance and domestic pressures, might withdraw support for tight U.S.-led export controls. ASML’s CEO, Peter Wennink, had previously expressed discomfort with the restrictive export policies which have cost his firm double-digit percentage revenue decline, viewing them more as economically driven than genuinely tied to security concerns. Faced with intense domestic lobbying from its largest technology firm, the Netherlands could allow ASML to restart or significantly increase its sales of advanced DUV lithography machines to Chinese chipmakers. While still initially hesitant on EUV technology, even that could become negotiable if U.S.-Europe relations deteriorated sufficiently.

Germany, France, and other European states might similarly decide to prioritize their own economic and technological interests over alignment with a hostile U.S. trade stance. European manufacturers and chemical suppliers, vital to the global chip supply chain, could loosen their compliance with export controls, quietly resuming or increasing trade with China. Over time, this hypothetical European realignment might significantly undermine the efficacy of U.S. semiconductor export controls, essentially rendering the American “high fence” strategy ineffective.

Simultaneously, Asia would likely respond pragmatically. South Korean giants Samsung and SK Hynix, deeply invested in Chinese production facilities, might push their government to quietly disregard U.S. export restrictions. Facing punishing tariffs from the U.S., South Korea would feel less compelled to follow American policies that run counter to its own economic interests. Similarly, Japanese semiconductor equipment firms like Tokyo Electron and Nikon, hurt by U.S. tariffs and anxious to regain lucrative Chinese markets, could lobby Tokyo to quietly relax export limitations. Even Taiwan, though strategically dependent on U.S. security assurances, might cautiously explore less sensitive chip technology exports to China to maintain competitiveness against South Korean and Japanese rivals.

These hypothetical policy shifts could result in a dramatic technological windfall for China’s chipmaking ecosystem. With renewed access to high-quality equipment and crucial materials, Chinese manufacturers could accelerate their development. Companies like SMIC and Huawei, previously restricted to older process nodes and struggling to innovate under sanctions, would potentially gain a fresh lifeline. Huawei, already successful in expanding HarmonyOS domestically, might swiftly regain global competitiveness in smartphones and infrastructure equipment. With less effective export restrictions, China’s domestic chip industry might progress far more rapidly towards advanced chipmaking, reshaping global market dynamics significantly.

This shift would also profoundly influence emerging markets across the Global South. Nations previously balancing their technology purchases between U.S. and Chinese suppliers might decisively pivot towards China, attracted by competitive pricing and availability, and hurt by US tariffs. Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa could see a major uptick in Chinese digital infrastructure deployments, from Huawei’s 5G networks to Alibaba’s cloud computing services. Even major emerging powers like India might adopt a more explicit stance of “multi-alignment,” carefully balancing technology relations between a now-isolated U.S. and a newly accessible China, seeking maximum economic benefit from each.

A long-term implication of this speculative scenario could be the bifurcation or at least substantial rebalancing of global technology ecosystems. While previously dominated by American and Western standards, a new equilibrium could emerge in which China’s technological influence significantly expands, setting global standards in areas like telecommunications, AI ethics, and digital governance. Europe might selectively adopt or tolerate Chinese standards, particularly in markets where interoperability with China becomes crucial. Two distinct ecosystems could emerge, with Chinese-centric standards prevalent in much of the Global South, and U.S.-dominated norms confined to North America and close partners such as the UK and Australia, if indeed Australia doesn’t pivot to China as well given its strong trade with the country and position in APAC.

Yet this hypothetical scenario carries both risks and opportunities. Technological innovation might thrive independently in multiple hubs, driven by increased competition and regional investments. Conversely, fragmented standards and reduced global collaboration could slow overall innovation, creating redundant efforts and inefficiencies. Economic growth would shift more definitively eastward, benefiting China and its trading partners, while potentially exacerbating stagnationary pressures in the U.S. and allied markets isolated by tariffs and reduced market access.

Ultimately, the potential fracturing of the global semiconductor alliance illustrates the dangers inherent in coercive and unilateral approaches to international technology policy. A careful balance is crucial; alliances held together by shared benefit and mutual trust are fragile and easily disrupted. While technological containment policies may seem justified from national security perspectives, overly aggressive measures that alienate critical partners carry enormous risks.

Its clear how rapidly and dramatically global alignments might shift, undermining American leadership in technology and reshaping the global economy in ways difficult to reverse. The scenario serves as a stark reminder that cooperative diplomacy, rather than isolationist confrontation, remains crucial to navigating the complexities of the global technological landscape. That lesson seems to have been lost on Washington.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy