On Wall Street, it’s called Trump-induced volatility, and the message of the past few days is that investors—and everybody else—had better get used to it. At the weekend, the President made good on a signature campaign promise, imposing twenty-five per cent levies on Mexican and Canadian goods and ten per cent on Chinese imports. On Monday, after Claudia Sheinbaum, the Mexican President, said that she would send ten thousand troops to fight drug smuggling at the southern border, the White House said it was suspending the tariffs for a month. Later in the day, Trump spoke with Justin Trudeau, the outgoing Prime Minister of Canada, who made a similar pledge, and came away with a similar pause.

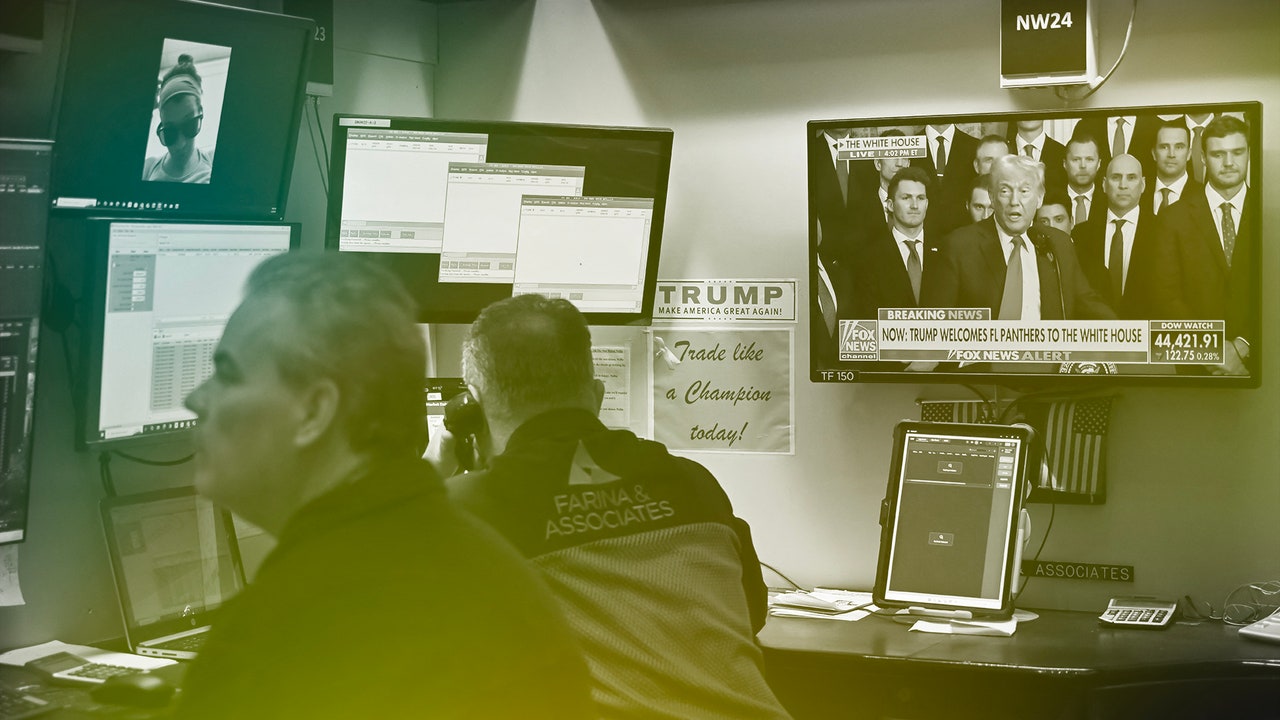

Both Mexico and Canada are acutely vulnerable to such pressure: the U.S. accounts for about eighty per cent of their trade. Trump, for his part, was under a lot of pressure from the business world to back down, and when the President paused the tariffs, the pro-free trade editorial page of the Wall Street Journal ran with the headline “Trump Blinks.” In the markets, news of tariffs led to an early sell-off; the market rebounded on the news of the pause. At the close of trading, the S. & P. 500 index was down less than one per cent. On Tuesday, the markets didn’t move much.

Some investors are still hoping that Trump’s threat of sanctions is merely a negotiating tactic to force concessions from trading partners. Or, as Scott Bessent, the former hedge-fund manager who is now Treasury Secretary, told the Financial Times in October, “it’s escalate to de-escalate.” Perhaps. But since his Inauguration, Trump has made clear that he plans to upend the international trade system and assert U.S. economic power in ways that are fundamentally antithetical to how the world economy has been organized since after the Second World War—a period in which American inflation-adjusted G.D.P. per capita rose from roughly fifteen thousand dollars to nearly seventy thousand dollars, while, in recent decades, workers’ wages stagnated and inequality increased sharply.

Trump campaigned on using trade policy to protect American workers, but his willingness to push around America’s neighbors, Mexico and Canada, as well as Greenland, Colombia, and Panama, is part of a broader agenda that is more accurately described as economic imperialism than as mere protectionism. One definition of economic imperialism is a strong country using its power to exert control over the economic resources and policies of weaker ones. The pretext Trump cited for the tariffs on Mexico and Canada was the inflow of fentanyl. This is certainly a serious problem, posed particularly by Mexican drug cartels: last year, authorities seized ninety-six hundred kilograms of the drug at the southern border. However, the total amount of fentanyl seized at the northern border in 2024 was a mere nineteen kilograms, according to the New York Times. Canada is not a major source of the fentanyl killing Americans, and the real reason for Trump’s animus toward the country appears to be that it runs a trade surplus with the United States and that its leader hasn’t been sufficiently deferential to him.

Over the weekend, Trump claimed on his Truth Social account, “We pay hundreds of Billions of Dollars to SUBSIDIZE Canada. Why? There is no reason.” And on Monday, speaking to reporters in the Oval Office, he repeated his assertion that Canada should become the fifty-first state. Of course, the United States doesn’t spend a dollar to subsidize Canada. Just as is the case between many advanced economies, a lot of commerce goes on across the U.S.-Canada border. In 2023, Canada imported $440.9 billion worth of U.S. goods and services. To be sure, we also imported a lot of goods and services from Canada: $481.6 billion. This created a bilateral trade deficit of $40.7 billion, equivalent to less than 0.15 per cent of the U.S. G.D.P.—hardly an alarming figure.

Moreover, trade in goods and services is only part of the U.S.-Canada economic relationship. Financial capital also moves across the northern border in search of profitable investment opportunities, such as purchases of businesses or real estate. In 2022, according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the total stock of Canadian direct investment in the United States was $589.3 billion, compared with U.S. direct investment in Canada of $438.8 billion. In other words, the United States was running a surplus on investment capital. Quite possibly, Trump himself has benefitted from this inflow by selling condos to wealthy Canadians. If he has, he hasn’t mentioned it.

As for the trade deficit, much of it is accounted for by energy products, particularly crude oil and natural gas, which Canada exports to the United States in large quantities. If the tariffs go into effect, the price of these products will go up for Americans. Over the weekend, Irving Energy, a Canadian company that supplies propane to Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, warned that it would pass the levies on to its customers. That’s what happens in trade wars.

The auto industry plays a key role in U.S. trade with Mexico and Canada. Since the North American Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1993, U.S. and foreign-owned automakers have reconstituted their manufacturing operations. General Motors, for example, now assembles about forty per cent of the vehicles it sells in the United States in Mexico and Canada. And the level of cross-border integration goes well beyond final assembly. Much of the industry’s supply chain is organized on a continental basis, some parts crossing a border several times before they are shipped out as part of a finished car or truck. As Paul Krugman pointed out in a Substack post, the Trump tariffs threaten to blow up this entire model.

And for what? Trump’s rhetoric sometimes suggests that his goal is to make the United States self-sufficient in virtually everything; the last major capitalist economy to achieve such a goal was Nazi Germany. At other times, including over the weekend, he has celebrated tariffs as a revenue source for the federal government, and suggested that they are better than income taxes. But, if tariffs were to become a major source of revenue, they would have to be substantial and permanent. What, then, of “escalate to de-escalate”?

It’s surely sufficient to know that Trump regards tariffs as an effective tool to bully other countries, and that his recent experience with Colombia appears to have strengthened this conviction. (After Colombia’s government refused to accept military flights of migrants deported from the United States, Trump slapped heavy tariffs on the country, prompting a quick reversal on Colombia’s part.)

On Sunday, Trump signalled that the next step would be the announcement of punitive tariffs on goods from the European Union, which has long been one of his bêtes noires. The way things are going, it wouldn’t be surprising if he singled out Denmark, which exports a lot of medical products, including Ozempic, to the United States, for specially punitive treatment, as a means of pressuring it to make concessions on mineral-rich Greenland, which figures prominently in his imperialist ambitions. (He’s already had one phone call with the Danish Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen. The Financial Times reported that it “had gone very badly.”)

So far, China, the prime target of Trump’s first-term trade war, has got off relatively lightly, with a ten per cent across-the-board tariff. (During the 2024 campaign, he had threatened a levy of up to sixty per cent.) On Tuesday, China announced retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports of crude oil and natural gas, farm equipment, and certain other vehicles. As many big U.S. firms, including Apple, Intel, and Tesla, remain heavily dependent on Chinese supply chains, the government in Beijing has the capacity to inflict a great deal more hurt on the U.S. economy, but its measured response signalled it is open to negotiations, and some of Trump’s business allies may well be advising him to exercise caution. In the meantime, he is busy bullying the vulnerable and figuring out how far he can take things without creating a financial crash. ♦