At 156 centimetres tall and weighing only 46 kilograms, Moowan doesn’t look big enough to annoy anyone. But she’s part of a generation of young women in Southeast Asia who delight the fashion and beauty retailers at the same time as they would drive environmentalists in the West, if they knew what was happening, crazy. Here in northern Thailand, environmentalism is almost nonexistent, as it is in most of developing Asia where people work hard for low pay, but where fashion-conscious women dr

dress and groom themselves immaculately. It’s a region of the world where phrases like ‘carbon emissions’, ‘overconsumption’ and ‘resource depletion’ draw only blank stares. So there’s a trend that Moowan and her peers participate in that goes unnoticed by any activists: they don’t buy clothes and accessories exclusively just to wear them; they buy more than they can possibly wear and create a huge in-house boutique for themselves, offering almost infinite choice when they are deciding how to dress in the morning.

While fast fashion is synonymous with ‘buy, wear a couple of times, and throw it away’, that assumes the buyer will actually wear an item at least once or twice. Fashionistas in this part of the world have tweaked the formula to ‘buy, maybe wear it, maybe not, and throw it away’.

Moowan is a case in point. She works at a large, popular kiosk that serves beverages inside a vast food court attached to a flea market in the Thai provincial capital of Udon Thani, about 500 kilometres north of Bangkok. The busiest hours on her shift are between about 7-9 pm, but outside that, she has time to work social media and do her online shopping between delivering drinks to tables and clearing away the empties. She is expected to dress snappily, and that she does, and with social commerce platforms like TikTok, she can afford to.

Moowan, like all her friends, buys everything online because her lifestyle doesn’t permit enough time to go out and do a lot of shopping in malls. She buys all her clothes, shoes, makeup, skincare products and costume jewelry online. She buys mostly from TikTok and Shopee, and although she works adjacent to a street market with a fashion and jewellery focus, she never shops there, or indeed at any street market.

“They buy from the same places as I do”, Moowan explained in her excellent English. “They buy online, mark it up and resell it, so if you buy in the market, you pay too much.”

She shops at least once a week, but has friends and colleagues at work who buy clothes more frequently. “I have one friend who buys every single day,” she said with a mischievous grin. “She has everything delivered here to the shop because there isn’t anyone at her apartment building who accepts packages at all hours.”

Moowan and her peers are also very particular about pricing. “I never ever pay more than 250 baht (approximately $8) for a dress or any other kind of clothes,” she said. “Yesterday I bought a pair of shoes for 200 baht.”

Bringing the shop home

The clothes being so cheap but at the same time trendy means that these young women buy so much and so often that they are effectively creating a whole store in their own homes. Each item represents a choice that she can make, but may never actually do so.

This is a variation on a familiar theme: while shopping in a physical or online store, there are things that you might like but you don’t buy, so you never actually wear them, but in this case, you do buy them, and you still might not wear them. “Sometimes I buy things and I forget that I have them,” said Moowan. “Sometimes I put things in a box and set them aside for the future, or I give them to friends or resell them myself.”

Moowan and her friends typically prefer TikTok and Lazada because they can mostly buy items that are made in Thailand. “I don’t buy from Lazada,” she said, “because there is too much ‘made in China,’ and when the stuff arrives, you find it isn’t what you thought it was.”

While lack of time constrains her ability to go out shopping, it evidently doesn’t prevent her from spending as much time as she pleases to decide what to wear each day. “It usually takes me an hour to choose what I wear,” she said. “I had to buy a second wardrobe and even then I need to stuff things in there to be able to close the doors,” she said, making a forceful pushing motion with her hands to demonstrate how she gets the clothes in.

A challenge for Mother Earth

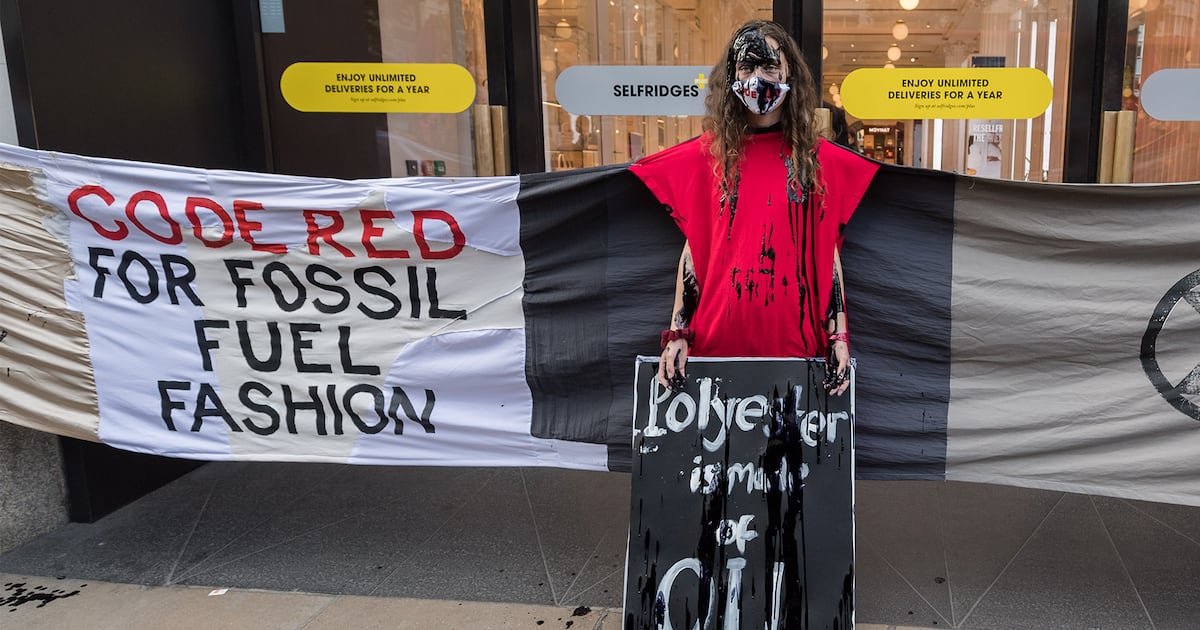

It’s a story that’s been swatted around for years about fast fashion: that it encourages overconsumption, uses vast amounts of textile, chemical and water resources, and produces as much 10 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gases.

Fast fashion retailers have responded in a number of ways to make themselves look virtuous: from recycling and resale programs to rejigging both fabrics and production methods to use less energy and other inputs. However, you only make money when you sell something, and everyone understands this, which is why the landfills keep filling up. It is simply an economic imperative that you cannot cover up.

Ultimately, the only way you can prevent serious environmental impact is to stop consumers like Moowan from buying so much so often that they are effectively opening stores in their own bedrooms.

Though not fast fashion retailers themselves, platforms like TikTok and Shopee are enablers of meaning and excitement in the lives of tens of millions of young people in Asia, who otherwise face very significant daily challenges.

In the end, it comes down to which morality you want to choose: unfortunately, we can’t have it both ways.

Further reading: “Fast fashion is a false economy”: Vestiaire Collective’s Fanny Moizant