I’ve arrived in the middle of a vast expanse of what looks like green LEGO plastic subdivided into fenced lots. Mozart’s “Turkish March” plays sourcelessly over a chorus of meowing cats and squeaking mice. A signpost with my name on it indicates that one of these lots of Gumby-colored virtual earth is mine, and it is embarrassingly barren. In contrast, the neighboring garden, belonging to a stranger going by Level12Arsonist, resembles a neon Eden, bulging with glowing vines, buzzing bugs, monkeys, and exotic fruits. I plant a carrot seed and wait for it to sprout. I’m informed I can buy a “bug egg” with funds drawn directly from my in-game checking account, though I have no idea exactly how much this costs or what it might do. Level12Arsonist, in a gesture of goodwill or perhaps pity, sends me a friend request. I am currently playing one of the most popular online video games on the planet.

Grow a Garden, available on the app Roblox, is an exercise in patience. As the name suggests, the premise is almost Zen-like, requiring nothing more of players than planting seeds and waiting — and waiting some more — for them to mature. Then they harvest their crops, sell them for “Sheckles,” an in-game currency, and gradually reinvest their profits in more seeds and more waiting. Or they can simply spend real money on Robux, Roblox’s universal virtual currency, to skip the waiting altogether and transform their plot of land into a verdant oasis.

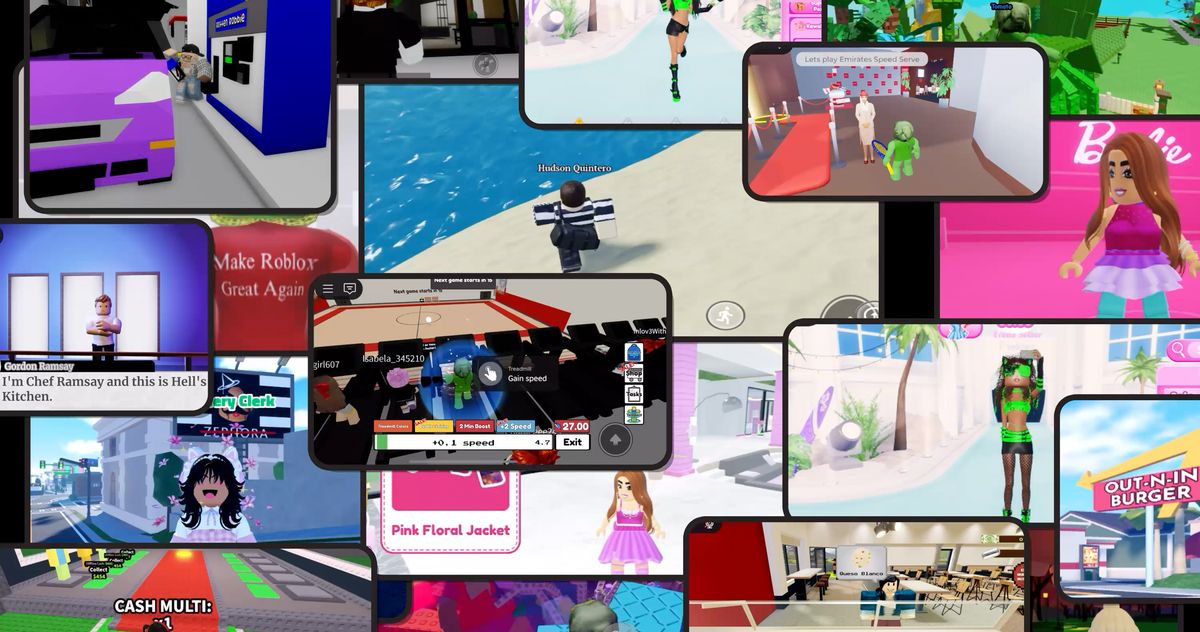

Roblox features millions of such games, many of them generated by the very children who play them. Grow a Garden — essentially a remake of the legendary time-waster FarmVille — recently smashed Fortnite’s all-time popularity record for concurrent users; at one point this summer, roughly 22 million people were playing at the same time. Grow a Garden is outpacing prestige games with development budgets approaching those of Hollywood blockbusters, put to shame by Roblox’s blocky graphics, a blurry mix of Minecraft and South Park. Grow a Garden was created by an anonymous teenager.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its primitivism, tens of millions of people around the planet love Roblox deeply, sincerely, and with more zeal than anyone loves just about anything else on the internet, their obsession spilling over into YouTube fan accounts, conferences, meetups, and a thriving industry of third-party coding studios. The platform’s popularity is staggering. In 2020, as Facebook continued to watch its share of the global adolescent attention span slide, Roblox told Bloomberg that “two-thirds of all U.S. kids between 9 and 12 years old use Roblox, and it’s played by a third of all Americans under the age of 16.” This year, Roblox reported 111.8 million average daily active users. Like many budding tech companies, it has yet to turn a profit, but it estimates it will end 2025 with around $4.5 billion in revenue and has a market capitalization of nearly $90 billion.

Where Mark Zuckerberg’s efforts to create a “metaverse” failed so profoundly his company pretends it never tried in the first place, Roblox presses onward with a living and breathing metaverse that has developed organically over time and with much less Wall Street fanfare. Co-founder David Baszucki describes the company’s mission with a phrase that has the ring of early Facebook idealism: “Connecting a billion people every day with optimism and civility.”

The reality of Roblox is less benevolent. It’s difficult to define this world, which is sprawling and diverse, with any precision. Brookhaven, which has been played more than 71 billion times and typically hosts 500,000 simultaneous players, offers gamers a virtual cityscape where they can act out fantasy lives as baristas, ICE officials, or simply pedestrians. Some games are hardly games at all; I spent longer than I will ever admit in a Roblox world consisting of nothing more than users waiting on a digital line for their turn to be cradled in the arms of an unlicensed Shrek sitting on a giant outhouse toilet. (Shrek Line, at the time I write this, has been played more than 25 million times.) Many popular Roblox games lean heavily into the “brain rot” cultural genre popular among internet-addled children with gameplay mechanics seemingly designed to be as incoherent or absurd as possible. Steal a Brainrot, for example, has gamers watch a procession of 3-D models based on Italian AI-slop memes that they can then buy and steal from one another as they avoid getting hit with baseball bats or slapped by giant hands. This game has been played more than 19 billion times, according to company metrics.

Like any platform synonymous with children, Roblox has become associated with their predation. According to data compiled by Bloomberg Businessweek, between 2018 and 2024, more than two dozen adults have been arrested on suspicions of abducting or abusing victims they met or groomed using Roblox. In one notorious case, a New Jersey man was sentenced to 15 years in prison after Ubering a 15-year-old girl he’d met on Roblox to his home, where he repeatedly sexually abused her. In recent months, Roblox’s stock has been buffeted by reports that it will soon face hundreds of lawsuits alleging that it has facilitated the sexual exploitation of minors, even as it touts a raft of new safety features to protect children. Furthermore, because many of its games are created by children who often see little or no remuneration, Roblox has been accused of being a largely unregulated, multi-billion-dollar child-labor operation.

These are serious problems. The bad headlines, however, can obscure other issues that may not be as sensational but are nonetheless widespread, affecting the teeming millions of children who hang out unsupervised in this vast playground. Despite heightened awareness of the dangers the screen life poses to children, parents seem largely unaware that Roblox is a wholly different animal from the usual smart-phone addiction. It’s a place where some of the most insidious trends of the contemporary internet — gambling, compulsive distraction, mindless consumption, and overall enshittification — have hardened into governing realities.

Company executives say it’s a site for unparalleled creative expression. “At the very highest level, one of the things we believe about Roblox is it should be really easy to create,” VP of engineering Nick Tornow told me in an interview. “We believe in the creation of anything, anywhere, by anyone.” But what executives are less willing to acknowledge, at least among those who aren’t the company’s shareholders, is the degree to which this great unruly world created by children has since been engineered to hook them on gamified consumption. What Roblox most resembles is a mall — if a mall could be limitless, free of the confines of brick and mortar. The kids in this mall are ostensibly doing normal mall things, the stuff you may remember doing when you were that age: gossiping, listening to music, goofing around, shopping, trying on outfits — and being asked at every turn to pay for, say, plants for their garden. Roblox presents players with a lopsided choice: the thrill of watching a tomato plant grow, free of charge, or the instant gratification of a lush, instantly generated garden at a price.

And there’s so much more: a virtual universe besieged by corporations and advertisers looking not only to make money but to embed themselves deep in children’s psyches. Even a few hours spent in the game’s various and ever-multiplying worlds is enough to make the shopping malls of old look like a Quaker youth retreat. The Robloxverse is a vision of hallucinatory hypercapitalism that dazzles and entertains as it extracts money from the young and inexperienced and impatient, immersing them in a degraded iteration of the internet where slop and the market and social media are totally integrated. Roblox’s legions of devoted fans see no such thing — only a chance to play, chat, and explore. It’s unclear whether Roblox executives, or the children’s parents, even care that this might be an illusion.

Roblox was founded in 2004 by Baszucki, a Canadian American radio host turned software engineer, and Erik Cassel, who died from cancer in 2013, making Baszucki, now worth an estimated $7 billion, the company’s best-known executive. He has taken a quieter approach to tech billionairedom and has little apparent interest in immortality, combat sports, or dismantling the administrative state. In contrast with his more reptilian fellow chief executives in Silicon Valley, Baszucki is kindly and avuncular in public appearances, like a friendly bespectacled neighbor you would trust to watch your kid — or millions of kids.

Baszucki envisions his metaverse eventually spreading to the worlds of work and family, but for now he is making progress on conquering fun. The software that eventually became Roblox was incubated in an early educational venture that Baszucki had hoped would teach schoolchildren about physics. The accessible design tools spawned something else; educational content can be found in certain remote corners of Roblox, but the prevailing vibe is recess chaos. And while some Roblox developers have crafted polished, visually impressive worlds, many of Roblox’s lo-fi games are jittery and glitchy even when running on modern hardware, at times so broken that this becomes a source of entertainment unto itself.

What Baszucki stumbled on was the realization the future of gaming wasn’t pyrotechnic graphics and ever-more-complex gameplay but the opposite. Unlike more sophisticated platforms, Roblox is profoundly accessible. You can run it on virtually any phone, the family tablet, or an aging PC. The official Roblox system requirements ask only that your computer’s processor have been manufactured after 2005.

Roblox is as easy to pick up and play as it is to install and run. It’s quick to download and quick to launch, and you can easily quit a game and switch to another. It’s a system that capitalizes on an inability to focus. “I think the biggest difference now between older gamers and younger gamers is attention span,” said Zakary Wilson, a Roblox developer at Epic-Studios.gg. “Short-form content has massively, for the worse, reduced younger people’s attention spans.” Wilson argued this trend partially explains the popularity of Roblox’s jump-in, jump-out games, in which plots and characters tend to be absent.

Like a casino, a Roblox world is usually entered free of charge, which means the app has to earn money in other ways. One stream of revenue comes in the form of Robux, which is halfway between mining-town-company scrip and casino chips. No one is required to cough up their money, but those who opt not to pay find themselves subject to constant reminders of their choice: limited outfit selections, gameplay options locked behind timers, and hours grinding away on tedious tasks to earn in-game points that could be purchased outright. Whether optional boosts are viewed as actually optional depends on how much patience a child has.

Roblox is far from the first tech company to force users to choose between spending money and a somewhat obstructed experience. But it’s unique in blowing out that dynamic to create an intricate alternative economy in which both individual developers and mega-corporations stand to profit.

During a session inside an officially licensed Sonic the Hedgehog game, I found myself not launched into the exhilarating zooming, looping courses the franchise is famous for but standing in a starting area festooned with virtual billboards advertising ways to spend Robux. Before even getting to the part that could plausibly be described as a game, players must run past signs advertising a Character Sale, Mega Bundle, Legendary Spinner, Biker Shadow Bundle, Exclusive Nametag + Benefits, Chao Sale, Next World, Trading Hub, Daily Rewards, Chrome and Luminosity Golden Eggs, and new Friends and Trails. “Most Roblox game shops look a bit like Vegas stores,” Wilson told me. “They’re just very colorful and very bright and very liquid.” Some of these purchases, as is typical across Roblox, function more or less like kiddie roulette: As the name Legendary Spinner suggests, spending money here grants not even a desired virtual item or power-up but the chance to win a variety of different prizes.

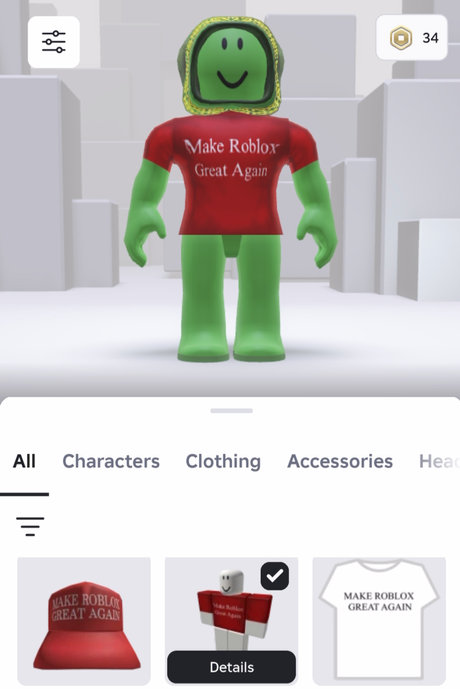

A great number of the accessories you can add to your in-game character to make it stand out from the other millions of players also require spending Robux. A MAKE ROBLOX GREAT AGAIN hat, complete with Trump signature, costs 95 Robux, while a wearable 3-D fish head paired with floating text reading DO YOU FART will set you back 55 Robux. An officially licensed pair of gold-laced Adidas sneakers will run you 34,200 Robux or about $130. In a 2023 Reddit thread, one parent asked Roblox users for help after claiming their 11-year-old spent $6,000 in roughly two weeks.

The actual worth of Robux is difficult to quantify. The exchange rate shifts over time and varies depending on where you trade in your dollars: $4.99 will net you 400 Robux on a console or phone but 500 on a computer or over the web. For $10 a month, you can have a “Roblox Premium” membership, which grants monthly Robux payouts and a better exchange rate. Once you’ve converted it, sussing out how much real money an in-game item is worth requires constant arithmetic, operations that get only more complex in games that use multiple fake currencies at once. Grow a Garden’s Sheckles require ever-changing amounts of Robux, the cost of which in U.S. dollars will necessitate a calculator, preparing young gamers for a future in currency trading if not agriculture.

Kids can make money on Roblox, too. Critics accuse the company of profiting from child labor, and to some extent this is true: Part of Roblox’s corporate revenue is derived from its take of money earned by children who build and sell virtual worlds and items, though Roblox notes that most developers are over 18 years old. On the unofficial Discord servers and message boards that host Roblox’s informal labor market, children and adults hire one another freely, paying either dollars or Robux. A developer who wished to remain anonymous given recent headlines about Roblox told me he started working on the platform as a teenager and learned a lot of lessons the hard way: “When you’re a kid, you hear a little bit of money, like $5, and you’re like, Damn, that’s a lot of money, right?”

Some developers have gone on to achieve undeniably great success. Rush Bogin began playing Roblox at age 7 at the urging of his friends. While his classmates’ enthusiasm waned as they entered middle school, Bogin was developing an interest in the platform’s design-tool set. In 2018, Bogin and a group of friends made a game that managed, through sheer zoomer ingenuity and tenacity, to land on Roblox’s coveted front page of trending games. Bogin remembers with pride the moment he’d earned the minimum required of developers before they are allowed to convert their Robux into hard currency.

In ninth grade, he was invited, along with a select group of developers, to join a program in which he could monetize his specialty 3-D creations and accessories. Crucially, this coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, creating a sudden wellspring of free time for Bogin and a flood of new and returning players to shop his wares. Early on, his accessories failed to grab attention. Bogin recalls waking early to check his overnight revenue. “I would always get really disappointed because it would probably get like five or six sales,” he said. “I just wasn’t doing well.” But as more and more people joined the platform, it became easier to generate viral hits. Rush launched one item — a “cute, winter beanie” — with no expectations. Suddenly, he woke to sales in the hundreds. Next, the beanie was the No. 1 virtual item on Roblox; today, Bogin says he has sold more than 2 million cute white winter beanies, which currently retail for 95 Robux, or about 35 cents. He now estimates he’s sold around 50 million virtual items, spanning a catalogue of 200-to-300 different pieces of clothing, hairstyles, and other customizations.

Predators and corporate brands are drawn to Roblox for vastly different reasons, but there is one common draw: Kids are easy to influence, and they can easily be reached on the app. Fairplay, an organization that advocates against manipulative marketing practices aimed at children, has concluded that a commodified virtual world like Roblox owes its success in part to the decline of “third places,” the sociological term for spaces that are not our homes or the schools or offices we’re required to visit; parks, malls, and movie theaters are all examples of third places, many of them bulldozed by the advance of online commerce, social media, streaming, and other technologies that render the physical world obsolete.

At the 2023 Roblox Developers Conference, executive Christina Wootton used tales of antiquity to underscore the platform’s positive contributions to society: “When I was younger, I used to hang out at the mall.” Malls are going extinct, she noted, but the dream lives on through Roblox. “People are together. They hang out. They shop. And we believe that social shopping is a massive opportunity for our community.” One Roblox executive I spoke to said the platform evoked childhood memories of spending their allowance at a neighborhood corner store.

The shopping malls of old, of course, existed to facilitate commerce, but they also allowed for crucial real-world socialization absent from digital spaces. “I am not going to sit here and be like, ‘The place to go is the mall,’” Rachel Franz, a former teacher now working with Fairplay, told me in an interview. “But the real, documented psychosocial manipulation of children in virtual spaces — you can’t replicate that in real life because real life has consequences. And it has smells, and time exists differently, and there aren’t gambling wheels that pop up in front of you in order to buy your Nike shoes, but then you spin wrong because the chances are terrible and you end up getting a sticker. Sometimes those exist in real life in casinos, but that’s why we don’t have kids in casinos.”

John Rutledge, a parent of three and a teacher at a Brooklyn private school, has seen firsthand how Roblox consumes the chatter of kids both between classes and back at home. “That kind of scares me a little bit,” he said. “It seems like Big Brother has too much control in a way. What Roblox is doing right now is they’re bringing these kids in and they’re just making consumers out of them.” Another parent in Brooklyn told me his 10-year-old daughter found games like Dress to Impress, in which you dress up avatars in clothes you purchase from an endless mall space, “relaxing” and “therapeutic,” the sort of thing you can do while talking to your friends either IRL or online.

What’s most disconcerting about Roblox is how easily it smuggles rampant consumerism into a kid’s life, says Franz. As part of her work at Fairplay, she conducted focus groups with Roblox-playing children as young as 10 and was struck by how little kids don’t notice or mind that the platform works to serve the flow of capital to Roblox and famous brands. “Kids consistently called out unfairness when it comes to paying-to-win mechanisms and virtual assets that give people an advantage when they pay more money,” she told me. “There was a lot of talking about how that’s unfair and it makes the game less fun. At the same time, they love spending time on Roblox.” While older gamers still roll their eyes at the latest Call of Duty asking you to exchange cash for a Snoop Dogg skin, Roblox players “spend a lot of time spinning gambling wheels and waiting for countdowns that will change the shop, or open a mystery box or that sort of thing, which I think doesn’t register as a mechanism by which the platform is serving corporate interests,” she said. When I asked Roblox whether the company believes children are psychologically equipped to handle playing roulette, a company executive stressed that parents are ultimately responsible and noted that the element of chance is fundamental to other kids’ games.

Some Roblox worlds seem to lean into the absurdity of the platform’s incessant money grabs. One game is little more than players running side by side on virtual treadmills to slowly generate points that could be used to buy in-game upgrades, allowing them to run better. Another has your character slowly climbing a ladder that stretches into the stratosphere, earning coins with each rung. Anyone wishing to bypass the monotony of running on a treadmill or climbing an infinite ladder can, of course, spend Robux.

A reliable supply of Robux requires access to a bank account or credit card, something out of reach for most young gamers. This means, as the company noted in its most recent earnings report, “a small portion of our users have historically been payers.” In 2025, out of more than 110 million average daily users, only a little more than a million purchased Robux. But as any casino knows, the most important thing is to get people in the door and keep them playing, which the company all but admits: “We believe that maintaining and growing our overall number of DAUs, including the number of DAUs who may not purchase and spend Robux, is important to the success of our business,” the company has said, referring to “daily active users.” As with Facebook, Instagram, and every other platform that trades on attention, engagement is the name of the game. As time goes on, “we expect more users to become payers and for payers, on average, to increase their purchase of Robux,” the company assured investors.

Fairplay takes particular issue with games “designed to be ‘unfun’ in order to drive microtransactions,” as a recent report by the organization puts it. Waiting for a tree to grow, idling on line to visit Shrek’s toilet, climbing an infinite ladder, the heretical idea of a speed-limited Sonic the Hedgehog — all instances of a game deliberately hamstrung to offer a glimpse of fun behind a gilded curtain. This is by no means a strategy invented by Roblox; free-to-play games that exploit our natural impatience date back to early-aughts hits like Neopets. The intervening years have seen game designers refine the science of doling out carefully dosed dopamine hits to hook players and pry open their wallets. But the sheer scale and popularity of Roblox makes groups like Fairplay worry kids don’t stand a chance. “They’re just developing concepts of money and economy and advertising when they get exposed to all of this,” Haley Hinkle of Fairplay told me. “And so it’s kind of beyond what we could reasonably expect them to understand.”

Youth-targeted brands like Nickelodeon and Mattel have naturally jumped into Roblox, creating promotional games that function as playable advertisements. Barbie DreamHouse Tycoon, for example, lets gamers deck out their own virtual dollhouse, though nearly every home improvement requires virtual currency. The Home Depot, Chipotle, Walmart and Sam’s Club, and LensCrafters have all created bespoke Roblox worlds. In 2022, Victoria’s Secret produced a Roblox world for its Happy Nation sub-brand aimed at kids ages 8 to 13. Kids who entered the Happy Nation hub navigated obstacle courses, filling their “Happy Meter” by collecting rainbows, which would eventually result in “celebratory fireworks, a boost in speed and doubled points,” according to a company press release. In addition to a full Happy Meter, players could walk away with a virtual tote bag and, most important, an increased familiarity with the Happy Nation family of products.

This year, Roblox announced a feature that lets companies sell and ship physical, real-world goods to gamers. Visitors at the Fenty Beauty Experience hop around on dazzling obstacle courses and take in the virtual scenery, but its raison d’être is the button that lets you buy $22 lip gloss.

Like every great tech company before it, Roblox knows that if you can’t get most users to pay, there’s still money to be made in advertising to the freeloaders. The marketing industry’s excitement over Roblox stems from luring prospective customers into bespoke virtual worlds: advertisements you can actually inhabit and explore, rather than static billboards. But the popularity of “advergames” on Roblox has drawn some criticism, mostly from advocacy groups. The advocacy group Truth in Advertising, which in 2022 sent a complaint to the Federal Trade Commission accusing Roblox of engaging in deceptive marketing tactics with children. The following spring, Roblox told reporters it was implementing restrictions for marketing aimed at gamers under 13. Roblox’s current advertising-standards policy instructs marketers that it is their responsibility to comply with these rules, namely “hiding all advertising content from users under the age of 13.” Many prominent brands seem indifferent. Advergames like H&M Loooptopia, Fenty Beauty Experience, and Alo Sanctuary are all described as appropriate for ages 5 and up.

“There is little to no evidence that Roblox is actively enforcing its current advertising policy concerning children,” said Bonnie Patten, Truth in Advertising’s executive director. “We actually have someone on staff who regularly logs on to Roblox, posing as kids under the age of 13 to see what kinds of advertising tactics she’s exposed to on the platform. Her engagement with the platform has led us to conclude that Roblox is using its ad ban as a shield.”

When I asked Roblox how advertising fits into its conception of child safety, company executives emphasized that most users don’t pay to play the game and that microtransactions are optional.

If Chipotle wants a virtual Burrito Builder, it pays a third-party developer to build it, not Roblox itself. To compensate, the company has in recent years reshaped its display-advertising system into something more akin to what’s offered through Instagram and Google Ads, in which ads appear where the user interfaces with the platform.

Ironically, what the company describes as “immersive” in-world ads closely resemble the pre-internet, pre-computer formats that have been around for centuries: virtual posters on virtual bus shelters in virtual cities, virtual billboards towering over virtual streets. A video demonstration on Roblox’s site shows avatars huddled before a sign reading EARN FREE ITEM BY WATHCING 15 SECOND AD — an ad for an ad! — and doing exactly that; after the Hugo Boss spot finishes, a beanie materializes on one player’s head, leading him and his friends to dance in a circle. ADD VALUE, the company exhorts. NOT INTERRUPTION.

That seeing a sign telling you to look at another sign in exchange for a hat could be considered anything but the definition of an interruption speaks to a seismic shift in what consumers consider intolerable. In Roblox, advertisers have access to not just a gazillion eyeballs but a population for whom corporations are just another parasocial relationship. These young consumers can barely distinguish advertising from anything else. “When we ask them, ‘Have you ever seen advertising in Roblox?,’ the young people in our focus groups were like, ‘Well, no, I’ve seen it on other games where there’s a pop-up ad for something. But in Roblox they don’t really do advertising,’” said Franz. “And then they said things like, ‘Well, you know, we’ve seen Chanel bags in the Roblox shop, but I don’t think that’s Chanel advertising.’ We know that stealth advertising works really well on young people because they can’t register it as advertising.” Indeed, Roblox says a brand’s mere presence “does not always qualify it as an advertisement” and that the onus is on the brand to decide whether its content is an ad.

A 13-year-old Roblox player I spoke to, who began playing at age 7, described being desensitized to branded content over the years. “It’s kind of been normalized since I’ve played it for a long time,” he told me. “And I feel like it’s been normalized to a lot of other people too.” A 10-year-old Robloxer put things more plainly. What is Roblox to her? “It’s just hanging out.” And is the presence of brands while hanging out normal? “Well, to me it is.”

Developers can also glean data about how exactly gamers are behaving. “Let’s say I was making a pizza-making game,” explained Heather Healy of Super League, a metaverse advertising agency. “I’d be able to track how many pizzas were made every day, what ingredients were most used.” Clever work-arounds by developers can help fill in gaps in data that Roblox doesn’t yet provide. Charles Weichselbaum, a VP at the public-relations firm Golin who previously helped launch Chipotle’s Roblox burrito-wrapping simulator, recalled adding virtual characters to branded worlds that existed solely to ask players personal questions like “Hey, what’s your gender?”

In this frenetic atmosphere of buying and selling, Roblox is keen to hype the successes of young developers. In a 2024 interview, Roblox executive Stefano Corazza described the opportunity for children to earn on the platform as a “gift,” particularly for those in the global South. But people like Rush Bogin are an exception. In 2021, the YouTube channel People Make Games published a video investigation titled “How Roblox Is Exploiting Young Game Developers,” detailing how the company entices children ages 13 and up into monetizing their work on Roblox. One of the channel’s hosts, gaming journalist Quintin Smith, pointed out that Roblox boasts that its top developers earn millions of dollars — “And so can you!” — while in reality, most will earn little to nothing.

Even if a game should become successful, how much money a lucky developer walks away with is not a simple matter. While PC-game storefronts like Steam take a simple 30 percent cut, Roblox’s take varies based on a byzantine variety of factors and differs based on what exactly is being sold. In some cases, a developer receives only 25 percent of money spent within a game on things like chance wheels and loot boxes. The split is so convoluted that a company page trying to explain it includes a pie chart, a flow chart, and caveats like “Note that the chart doesn’t reflect our expenses as disclosed in our GAAP financial statements.”

Also, all sales are tabulated not in real currency but in Robux — and can’t be withdrawn and converted into cash until you’ve hit a 30,000 Robux threshold. The inconsistent conversion-rate problem comes back to the fore here. Even if one reaches the point where the company will send real money, it does so on extremely disadvantageous terms: At current rates, spending $200 will get you 24,000 Robux. But converting 24,000 Robux a kid has earned diligently building and selling a game nets them only $91. The whole dynamic — encouraging children as young as 13 to do computer work, taking most of their earnings, and paying the rest in scrip — “would be illegal if it weren’t happening online,” Smith argued.

At last year’s Roblox Developers Conference, Baszucki presented a slide of five-year predictions for the company with dreamy ideas like a “universal civility metric” that “for most players, increases over time.” Baszucki imagined Roblox as a Fortune 500 hiring tool, a virtual meeting space, a medium for families to stay in touch, a school that creates a “full K-12 curriculum with Roblox.” And, perhaps auguring disastrous headlines to come, Roblox dating (for adults only).

The future of Roblox, according to Baszucki, is to bring the world together — but to do what, exactly? Shop? Yes. Learn of the latest tasty entrées at Chipotle while dressed as Sonic the Hedgehog in a bulletproof vest? Absolutely. Roblox seems to be not just rebuilding the shopping-mall experience but expanding it into a self-contained paradise of software consumerism that could truly eat the world. Not content with shopping and gaming, Baszucki wants Roblox to be the place where you will live your life. In more ways than one, the children really might be our future.

It may be wise, at this point, to bear in mind how poorly the video-game anxieties of yesterday have aged. There was a time when Doom and Grand Theft Auto were suspected of turning kids into murderers; the idea that violent games automatically created violent children isn’t just embarrassing in hindsight but largely debunked by decades of research and social science. I was also struck, no matter how horrified I was by Roblox’s cosmetics-pushing obstacle courses and casino pleasure gardens, by one thought: God, I would have loved this when I was 12. The platform may seem baffling to adults, but its charm is obvious. What could possibly be more enticing to any kid than a free game where all of your friends already congregate, that looks and sounds absolutely deranged and will alienate your clueless parents and teachers?

At the same time, the megapopular internet platform of my generation turned my peers and even our parents into screen junkies who spend their waking hours scrolling an infinite feed of slop and marketing that gets crappier and less useful by the day. What’s worrisome about Roblox is that the appeal of its universe — where slop and commerce and dopamine rushes are seamlessly blended — is that it’s intuitive. It’s the logical end point of the internet’s enshittification playing out before a younger generation’s eyes.

The total victory of Roblox’s vision may lie not in its ability to dominate us but in its ability to subsume “real life” to the point that we don’t even know it’s there. If this sounds unpleasant to you, you may soon find yourself a minority. Where older generations fretted about “selling out or giving in to the man,” Healy said, “the younger generation just doesn’t care.” Healy described publishing influencer videos to demographically distant internet platforms. “You could see the exact same video posted on Facebook with a lot of negative responses.” But put that clip on TikTok, Healy says, “that same piece of video content, you look at the comments and you see Gen Z and Gen Alpha saying, ‘Oh, go get that bag!’”

Roblox’s marketing allies share the company’s totalizing vision. Brent Koning of Dentsu, a marketing agency that works with Roblox, described the company as a kind of digital arcology where living, talking, shopping, and streaming are merged into one digital omni-existence. “That aspirational side is something that I long for and we talk to them about all the time,” he told me. Imagine, said Konig, being able to watch anything you want from inside Roblox. Your favorite Netflix show, maybe. While you’re waiting, you fire up Spotify to listen to your favorite music. Then you fire up Shopify in search of new sneakers. “I don’t know what they look like on me, so I go to Nike Land, and I can try them on real quick.” At no point have you closed Roblox, or looked away from your screen, or necessarily moved an inch.

Inside this mall, there is no time, no space, no entertainment, no socialization. These are labels of the old world, as relevant as Macy’s. Roblox is the super-experience, the final app. Go get that bag.