Andy Hazelton learned he’d been fired the same way everyone else did. Like hundreds of his colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, he received a mass email from the head of the agency at around 3:45 p.m. on Feb. 27 confirming his termination, effective immediately.

“They gave us ’til 5,” said Hazelton, a scientist who specialized in hurricane research and modeling at the National Weather Service, the meteorological branch of NOAA responsible for weather forecasts. “That was our cutoff. And then our email access was lost later that night, too.”

More than 800 employees were dismissed in February’s initial sweep across NOAA, a congressional source told CBS News after the firings. And more job cuts could be coming — all as part of a federal cost-cutting initiative by the Trump administration and the Elon Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE.

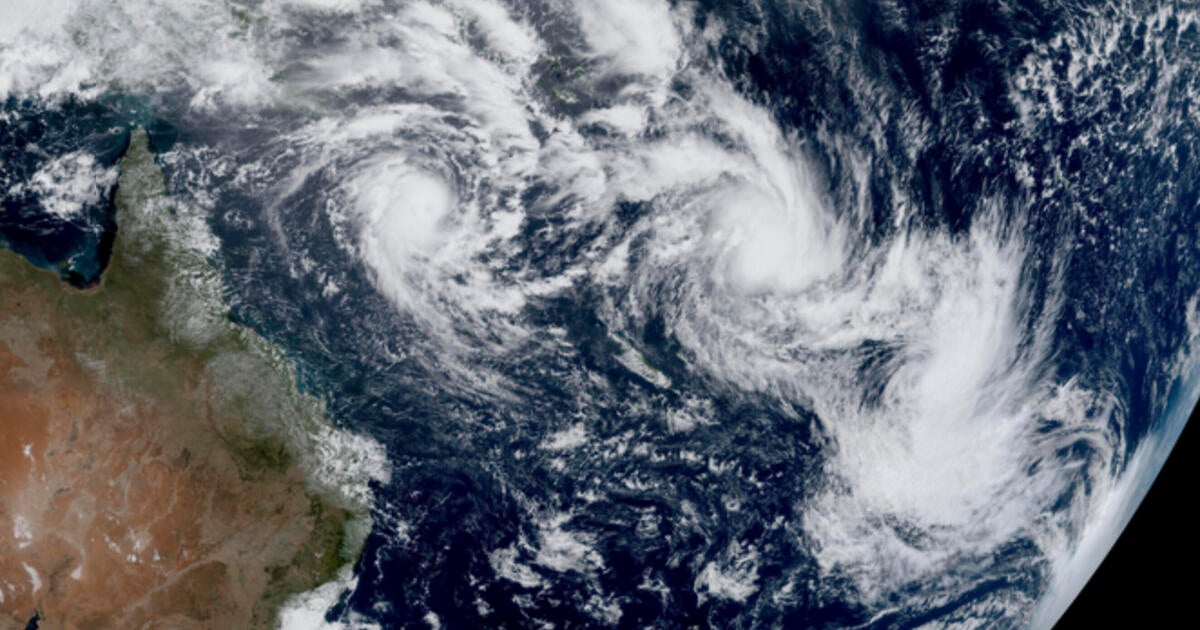

As the nation’s primary hub for weather and climate information and a leading source of environmental data overseas, NOAA is considered the authority on forecasting, storm tracking and climate monitoring. Many are warning that slashing its workforce could compromise the quality and accuracy of extreme weather forecasts that guide government responses to hurricanes, wildfires, tornadoes and floods, often providing life-saving predictions and warnings that don’t exist anywhere else.

The job cuts at NOAA “jeopardize our ability to forecast and respond to extreme weather events like hurricanes, wildfires, and floods—putting communities in harm’s way,” said Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from Washington state who chairs the Senate subcommittee that oversees NOAA, in a statement responding to the agency’s job cuts.

The American Meteorological Society, an organization that partners with NOAA, warned in a separate statement that “the consequences to the American people will be large and wide-ranging, including increased vulnerability to hazardous weather.”

Peak tornado season is now in full swing in the United States, where wildfire and hurricane seasons typically pick up in May and June but have started sooner and stretched on longer in recent years. Natural disasters are occurring with increasing frequency and strength because of climate change.

Hazelton’s termination came about four months into his tenure as a full-time federal employee at the weather service’s National Hurricane Center in Miami. On his first day, back in October, Hurricane Milton slammed into Florida’s west coast, and during his time at the agency he worked on a storm prediction program that provided data to inform track forecasts, hazard warnings and evacuation orders for storms like it.

“It’s hard to say for sure, but with fewer people working on upgrades to the models, and fewer people working on collecting the data that goes into these models, I think it’s quite possible that the model accuracy will not have continued the improvement that we’ve seen over the last five, 10, 15 years for hurricanes,” Hazelton said. “We may start to lose those improvements or even potentially reverse some of the skill and go backwards if we’re not careful. You know, especially if these cuts continue.”

A Trump administration official told CBS News the first round of job cuts at NOAA shrunk its staff by 5% and largely spared employees with critical roles, such as weather service meteorologists. But a source at the National Weather Service disputed that, saying some meteorologists including radar specialists were impacted, as were staff of the Hurricane Hunters crew, which fly airplanes into storms during hurricanes to help forecasters make accurate predications.

At least a significant portion of the cuts impacted workers in the “probation” period of their employment, which usually lasts 1 to 3 years after starting a full-time role, according to a NOAA source. Probationary employees aren’t necessarily novices, though. A weather service source said staff with 15 years of experience at NOAA, or more, could technically be categorized that way if they were recently promoted to a higher position.

NOAA is now preparing to lose more than 1,000 additional workers in a second round of firings, sources told CBS News this week. The agency could ultimately lose about 20% of its staff along with some of the programs they work on, although it’s not known which will be impacted.

DOGE has also announced it might terminate the leases of 19 NOAA offices nationwide, including key buildings that generate vital weather forecasts and maintain radar operations. Individual offices have already paused some operations because of a lack of workers. The weather service office in Kotzebue, Alaska, said shortly after the first wave of layoffs that it would stop launching weather balloons, which collect weather observations from the atmosphere, indefinitely, while NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory shut down its communications services due to staff reductions there.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, called the firings “shortsighted.” Without a means to replace lost employees or their work, Swain told CBS News he believes the situation could quickly devolve into a public safety threat.

“These literally are the people who are responsible for issuing a tornado warning during a tornado outbreak, or a flash flood warning during a flash flood, and we’ve seen plenty of deadly iterations of those kinds of things in recent years,” he said of NOAA staffers. “Same thing, by the way, when it comes to extreme wildfire conditions. The weather service office in L.A. was very active in the days leading up to and following the catastrophic fires just a couple of months ago.”

Swain said the reduction in NOAA’s workforce will make nearly every aspect of his job as a weather and climate scientist more challenging, and the firings stand to influence a broader network of industries, too.

“It will affect every single colleague that I have, working in any type of weather or climate institution, whether it’s public, private or academic,” he said. “It will really affect every single American, and, frankly, many people around the world, because NOAA is the backbone for providing virtually all of the basic weather information that is needed to produce global weather forecasts to observe and understand climate change, essentially, to predict the future, to lessen the impacts of disasters, you name it.”

Swain and almost 150 other scientists signed an open letter to Congress and the Trump administration before NOAA’s layoffs last month, calling for a stop to what they deemed an “increasing assault” on science conducted at U.S. agencies and institutions as earlier federal cuts hit the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy.

“Without a strong NOAA, a cornerstone of the U.S. scientific research enterprise, the world will be flying blind into the growing perils of global climate change,” read the letter, which urged Congress and the Trump administration to keep NOAA fully staffed.

Later, in a video shared to his YouTube channel the day of the NOAA firings, Swain said, “There will be people who die in extreme weather events and related disasters who would not have otherwise.”

NOAA declined to comment on the layoffs. In a statement emailed to CBS News, a spokesperson for the agency said “we are not discussing internal personnel and management matters.”

“NOAA remains dedicated to its mission, providing timely information, research, and resources that serve the American public and ensure our nation’s environmental and economic resilience. We continue to provide weather information, forecasts and warnings pursuant to our public safety mission,” the spokesperson said.

Rick Spinrad, who was NOAA’s administrator during the Biden administration, is worried about the impact on the National Weather Service, saying job cuts will “most assuredly” affect the availability, frequency and accuracy of weather warnings.

“I think at some point people are going to recognize we need these capabilities for the public good, which, after all, is the role of government,” he said. “The question is: how much damage will we sustain before we’re able to turn around the damage that’s already been done?”

Jordan Freiman and

contributed to this report.