Illustration: Rama Duwaji

In 1948, when the first Palestinian refugees were expelled from their homeland by Zionist militias, many who fled carried their house keys. The welded iron rattled in their pockets and dangled from chains on their waists as people traveled, often on foot, to safer territory. Some went to Gaza, others to the neighboring countries of Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Many believed the relocation would be temporary and anticipated spending only a few weeks away. But the weeks stretched into years and then decades. Families passed the keys down from one exiled generation to another in the hope that someone in their lineage might one day return and unlock the door to the place once called home. In the Palestinian diaspora, the iron key is a symbol of remembrance and resistance, of a promise to return.

Now, as a new wave of Palestinians are forced from their land in Gaza, many sense, or know, that nothing of their homes will remain if they are ever able to go back. The schools they attended, the beach cafés where they gossiped, the bedrooms where they dreamed of their futures — all are now rubble. Countless friends and family members are gone forever: murdered, starved, buried in the bombardment, or disappeared. What the survivors carry this time are relics. Here, five Gazan women tell the stories of the objects they took with them as they left their lives behind.

Illustration: Rama Duwaji

I was married only a year and a half when the war came. My wedding day was very beautiful. It was in a large ornate hall, one of the most grand in Gaza City. There were roses, and everything was like a dream. I wore a Palestinian thobe — a long, traditional gown with intricate embroidery. All my friends were there. We ate cake, and my husband and I danced. Everyone was happy.

But I didn’t get to experience my marriage. And I didn’t get to enjoy our life in Gaza with our daughter, Celia, who was only a few months old when she and I evacuated. My husband refused to leave Gaza at first. He thought that if enough people stayed, there would not be an occupation. Now, he is still there, and I don’t know how I can get him out. We don’t get to talk very often because internet service is rare, but I try to reach him for a little while each night. He is staying in a relative’s apartment now, and during the day he is usually busy looking for firewood, food, and water. When we talk, we talk about the food he misses from before the war: chicken, meat, vegetables. He tells me how he misses our child. He tells me his despair and frustration.

Recently, our conversations have become tense, and they’re getting worse. The distance is difficult, and the war has made him a more complicated person. He’s depressed. My heart hurts when we speak. We met at university, and we married for love. But we are cold to each other now. I don’t know exactly why. He makes me feel like I’m a traitor, like I left him. He thought this war would be like those in 2008, in 2014, in 2020, in 2022. He thought we would be able to return to our lives.

My child and I are lonely. I have always dreamed of escaping to America and Europe in order for Celia to live in safety — to any country, really, that gives us our rights as human beings. I think of it often now. I will try to do it, even if it costs me my life. My home has been a war zone for so long. I don’t want my daughter to live through what I have. I remember everything from the 2008 war, when we lived in refugee camps. I don’t want her childhood to be like mine.

I also brought Celia’s hospital bracelet from when she was born. Her clothes and toys were destroyed when the bombs came, and I wanted to have something to give her from Gaza when she’s older. I am afraid my child will grow up without a homeland as well as without a father.

Illustration: Rama Duwaji

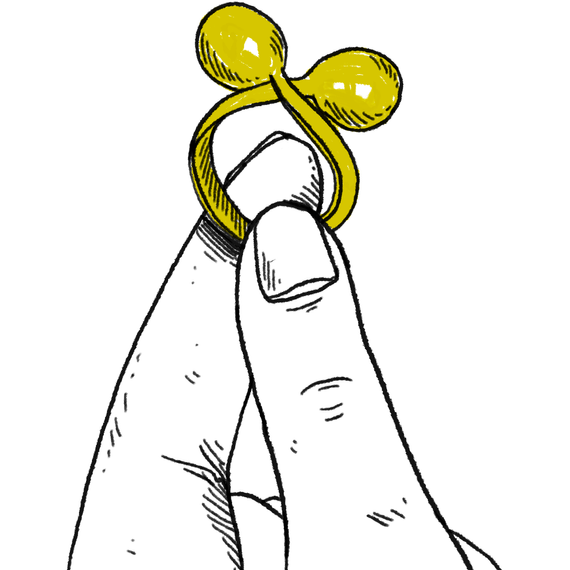

My ring is my most cherished possession. My mom, who is still in Gaza, gave it to me when I graduated from university. Every eight days, she tries to find internet to call me so I can hear her voice. She cries because I’m so far from her — I am now in Cairo, living in a small apartment in a poor neighborhood. My mom says she’s hungry. She loved her home, but it is gone, bombed. She loved her friends. They used to sit and drink coffee and eat sweets together. Most of them are gone too. She loved going to the sea. Every memory I have of her is now beautiful to me. I hope to see her again.

Illustration: Rama Duwaji

In June 2023, I traveled from Gaza to Cairo for infertility treatments. Besides my usual clothes, I took a Palestinian keffiyeh, a symbol of pride in our identity. I intended to return home in November after IVF, but in October, the war came and we were unable to go back. The treatment was successful, and in March of last year, I gave birth to the most beautiful baby boy, Shahada, named after his grandfather. We have not been able to celebrate him with our family. I am still in Cairo with my husband and his sister. My father, brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews are all dying in Gaza. Some of my family are in camps, living in tents, and some are in what remains of bombed-out houses. Before the war, my family was strong and generous. We owned homes, a shoe store, a supermarket, and a bakery where we sold Palestinian qurshala cakes — long, thin biscuits — petits fours, and cookies. We’ve lost everything in this criminal war. My husband’s brother became a martyr, as did his cousins. My husband’s sisters lost their husbands. We had a happy life in Gaza, but it’s over.

Illustration: Rama Duwaji

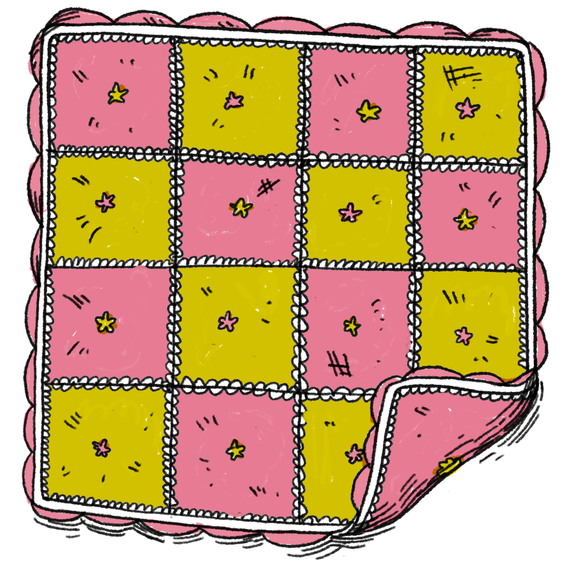

When I left, about a week before the Rafah invasion, I could pack only a single suitcase. My home had already been destroyed by bombs, and I pulled some of my belongings from the wreckage. The blanket reminds me of my mom — she made it herself. I used to join her in the living room when I got home from work; we would watch YouTube as she crocheted. She tried to teach me the stitches a few times, but I just didn’t have it in me. She is still alive, thank God, though she is still in Gaza. Our names were on a wait list for evacuation, and mine was called before hers. Now she is trapped. No one has been allowed to leave. My mother keeps reassuring me and my sisters that better days are coming. I think she is also trying to reassure herself.

The bits of concrete bring me back to my room in our home. It was beautiful and cozy. I had a bookcase filled with books — a gift from my aunt. The rocks remind me of how quickly things change. They tell me that nothing lasts forever, good or bad.

The piece of painted glass is from my days as a teacher. I taught English to children, and sometimes adults, at an institute one city over. All my students were curious and creative, and I loved being with them. The image on the glass is of a character I made up for the children, an old lady named Nazmeya. The idea was that she didn’t speak much English, and she would appear all over their worksheets, asking them for help translating words she didn’t understand. A student surprised me with this glass token at the end of our term. My final day of teaching was in February 2024. I keep in touch with the students as well as I can. I learned last year that one, Mohammed, was killed in an Israeli air strike. He was a kind soul — always smiling, always optimistic. That loss hit very hard.

Illustration: Rama Duwaji

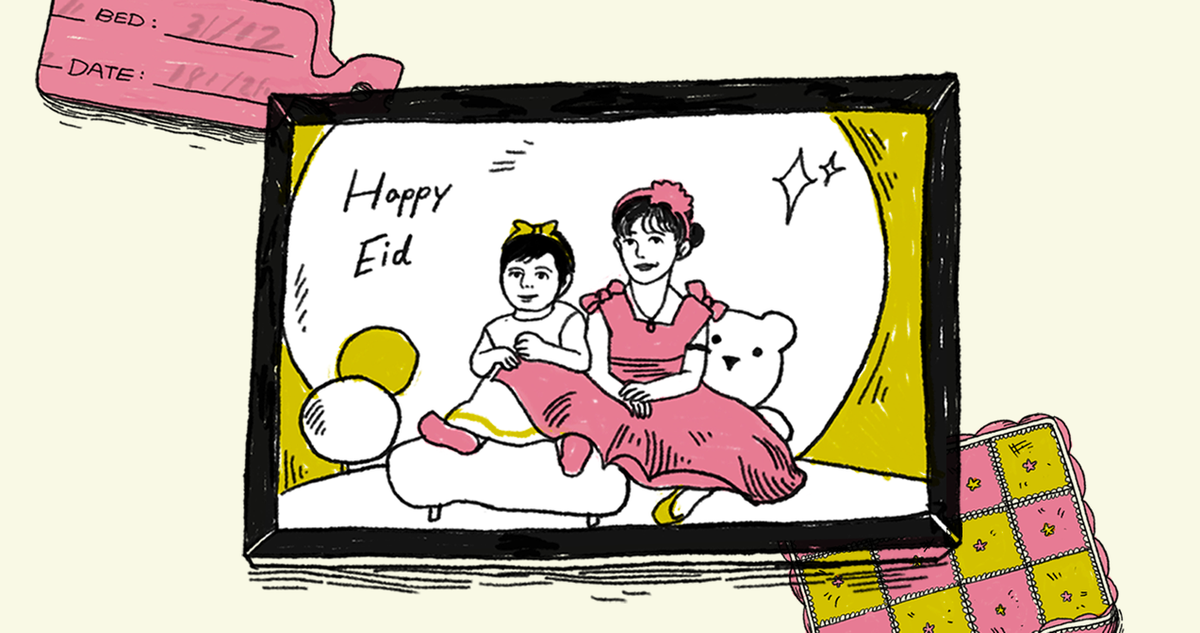

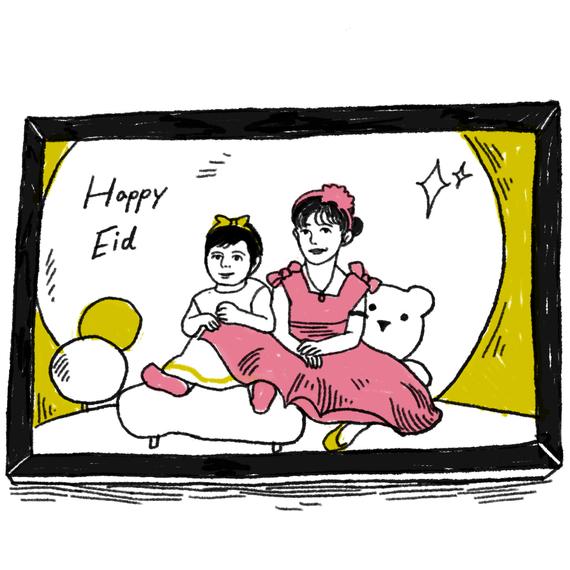

I left Gaza in April 2024. There wasn’t much time. Everything was frantic and filled with tears. Terrible fumes from the bombing hung in the air. It was the first time I’d ever packed a bag; I had never traveled before. Besides some light clothing, I took only a small box containing a gold-plated ring that my eldest niece had given me on my birthday two years before and a photo that I pulled from the rubble of my sister Samar’s house.

The photo is of her two daughters, my nieces Lina and Masa, when Lina was 4 years old and Masa was only 1 year and 4 months. I took the picture on the second day of Eid in the spring of 2023. I had taken the girls to a children’s carnival in Rafah, where we walked and ate chocolate ice cream, Lina’s favorite food. Later, I had the photo printed and put it in a small frame as a gift for the girls.

My sister and her daughters were stolen from me in an instant on October 23, 2023. Their apartment building was hit by a missile. Israel does not respect even the rights of children. Its military has thermal-imaging technology on its drones, and operators can see warm bodies inside buildings. They would have known the house was occupied at the time, and they would have known it was inhabited by children. My nieces’ tiny bodies were torn apart. Many other members of their family lived in the building — their cousins,their grandmother and grandfather. They were all killed. For months, every day, I went to what was left of the structure to look for them. The smell of blood and gunpowder rose from the stones. I tried tocollect anything with their scent. I found torn pieces of clothing and my nieces’ mattress, which was covered in blood and ripped apart. It had been blown to the far end of the street. Ninety people were killed. I couldn’t believe that they had left this world — that they no longer existed.

I live in a house in Cairo now, alone. The photo of my nieces reminds me of all the beauty I’ve had in my life. I have been trying to preserve that amid all this chaos, pain, and fear. Since the girls’ deaths, I’ve tried to hear their voices, and the voice of my sister, every night before bed. I say “good night” to them as if we were sleeping together. In the morning, I talk to them as if they were still alive. They will remain alive in my heart and mind as long as I live. Their photo will bear witness to the childhoods that were assassinated.

As for the ring Lina gave me, I never take it off. Every time I touch it, I feel that her little fingers are still holding my hand, telling me she loves me.