Earlier this month, with the fashion world awaiting Matthieu Blazy’s September debut for Chanel, the French luxury house staged its latest couture show in Paris, an event less noteworthy for the clothes — another collection signed by the design studio — than the spectacle.

Chanel again paraded its products through the stately Grand Palais, which it packed with a global roster of stars such as Lorde, Romy Mars, Sofia Coppola, Kirsten Dunst, Xin Zhilei, Wang Yibo, Penélope Cruz and Ramata-Toulaye Sy, providing fodder for dozens of posts on Instagram that generated millions of views, “likes” and comments.

Even Chanel isn’t immune from the pressure to keep posting.

“A product is basically content until someone buys it,” said Thom Bettridge, editor-in-chief of i-D. “And the second someone buys it, it then becomes content again, in the sense that you’re posting what you’re wearing … I just feel like, in a way, these types of things get consumed so quickly.”

For decades now, technology has been driving an acceleration in the speed at which cultural products like fashion are created and consumed, but things reached a frenzied new pace with the arrival of algorithmically curated social-media feeds serving up a miscellany of videos, photos, memes and more distributed according to what gets people to like, comment or just pause for a few seconds.

Attention, in this context, is currency, and what captures attention is often anything that triggers the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter instrumental in pleasure, reward and motivation that gives its name to “dopamine scrolling.” Over time, it creates an addictive feedback loop.

“There are brain studies showing that digital media activate the same reward pathway as drugs and alcohol,” said Anna Lembke, professor and medical director of addiction medicine at Stanford University’s School of Medicine and author of “Dopamine Nation.”

The consequences are greater than just hours wasted online. The music historian and critic Ted Gioia, whose argument that we’re in a period of cultural decline received attention from outlets such as The Atlantic earlier this year, has described this state of affairs as “dopamine culture,” writing in a 2024 essay that art and entertainment are being supplanted by mere distraction. In Gioia’s view, algorithmic feeds are atomising our collective attention and rewiring industries such as music, movies, sports and journalism, so that albums are less important than snippets of tracks on TikTok, films are losing ground to short-form video and so on.

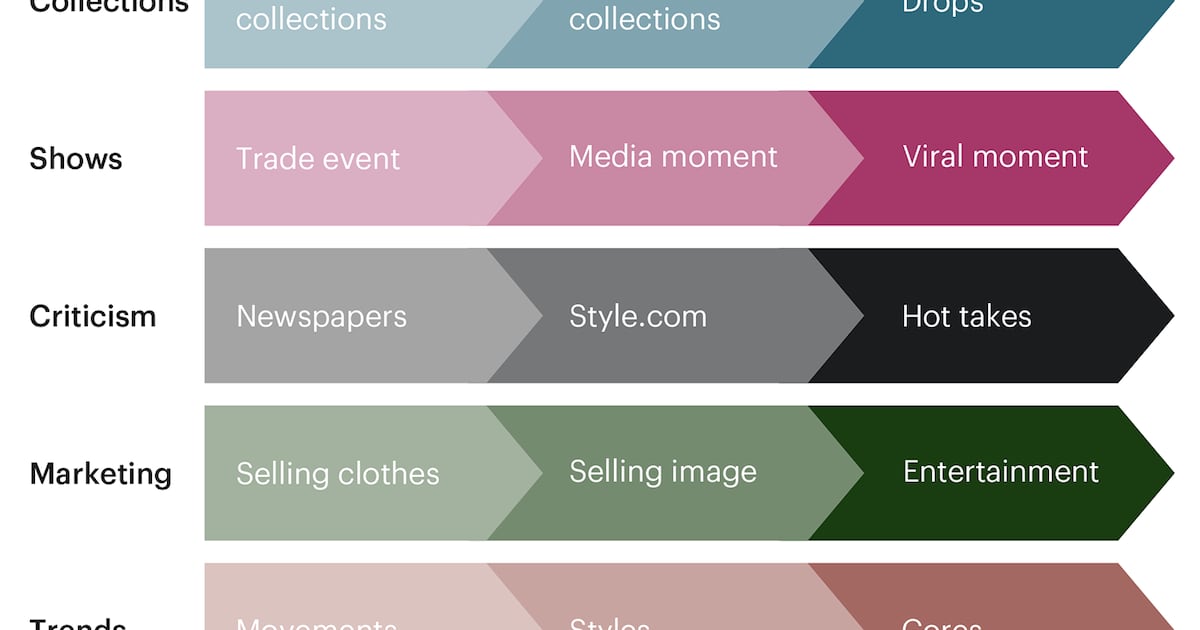

Gioia’s essay doesn’t mention fashion, but it easily could have. The fashion system has mutated under these same pressures over the past decade and more, giving rise to changes that can be seen in how people shop, the transformation of fashion media, the acceleration of the trend cycle and the pressure on brands of all sizes to keep up.

“What’s happening today is all these algorithms tapped into our addictive behaviour, and as any other industry, inevitably fashion and culture have been consumed like entertainment — always in search of the combination of the new, the exclusive, the unique, the now,” said creative director and photographer Ezra Petronio.

Dopamine Fashion

The view that dopamine culture is strangling artistry and sidelining complexity is controversial. In fashion, there are, after all, still designers producing exciting, thought-provoking work, such as Glenn Martens, whose first couture show for Maison Margiela earlier this month won raves. And although much of the new fashion media that gets views consists of hot takes or news and images with little context, there are also voices like Luke Maegher, who goes by Haute Le Mode, trying to offer deeper insights.

“I’m inclined to be a little bit skeptical of it as a holistic theory,” said Bettridge. “I don’t think the dopamine culture thing is bullshit; I think that it’s talking about something that’s very true. But it’s maybe not looking at the ways in which there’s actually still culture happening within those things that seem like slop.”

That said, dopamine culture has already rewired the fashion system in fundamental ways: If major fashion companies long ago shifted their core focus from designing clothes to selling an aspirational image, today they are increasingly in the business of producing quick-hit entertainment to be scrolled on your phone.

Luxury brands now maintain a near-constant cycle of seasonal and interim shows in photogenic locales to stay present in the minds of their customers, many of whom are never physically present but see only glimpses as pictures and video pop up in their social feeds. Trends that once lasted years, becoming movements or at least styles that stuck around, have given way to “cores” and microtrends like “cottagecore” and “mob wife” that might only last a matter of weeks on TikTok as shoppers demand a constant stream of newness to peruse and purchase before quickly moving on to the next thing.

Petronio said in the past brands had time to devise a strong campaign that would need to encapsulate their values and last an entire season. Today, they must release new imagery and products constantly, and the bigger the brand and the more touchpoints it has, the harder it is to maintain a coherent brand image and identity.

“It’s just a nonstop thing, and I feel that unfortunately sometimes it is a little bit desperate,” he said.

This environment exerts a great deal of pressure on all kinds of businesses, which face real risks if they can’t keep up. Laura Baker, co-founder of the multi-brand boutique Essx in New York, said she would like to take a short break from feeding the store’s social channels, but it doesn’t feel like an option right now. The shop, which does most of its sales in-store rather than online, has to constantly be holding events and telling people about them, or working with influencers and dreaming up other posts to stay at the top of people’s minds and keep business flowing. Baker loves the store and its customers, but it’s exhausting.

“If we go quiet for even a day people are like, ‘Are you guys ok?’” Baker said. “The consumers are on such a high of what we’re giving them. They want those activations. They want that marketing. They want that content. They want to see the product first. If we’re not keeping up with them, they’re just going to go to someone else.”

Recent years have seen a rise in runway stunts seemingly engineered to capture attention online, producing a number of viral moments like Coperni’s spray-on dress, applied live to a nearly nude Bella Hadid, and Schiaparelli’s faux taxidermy gowns featuring fake animal pelts, heads included. At Paris Fashion Week this past March, wunderkind Dutch designer Duran Lantink’s show received more attention for the prosthetic breasts he sent down the runway on a male model than the clothing. The look was inspired by the torsos of action figures.

“Fashion is meant to move people, so it was interesting to see how it sparked reactions and different interpretations,” Lantink said in an emailed statement.

At their most effective, these moments can be better for driving chatter on the internet than a front row of paid ambassadors.

Is It Good for Business?

As luxury suffers a sharp downturn in demand, many brands find themselves struggling to justify to customers why their products are worth their extraordinary costs amid soaring prices and accumulating reports of declining quality. At the same time, they continue spending huge sums on generating attention through stunts and spectacles whose impact they have raced to quantify with metrics like earned media value. It’s uncertain, however, how much these momentary digital interactions translate to sales. Petronio called the connection “nebulous.”

Many shoppers are increasingly left feeling like what they’re paying for isn’t top-tier craftsmanship and creativity but marketing, even as more of them keep hitting the “like” button.

“Brands are beginning to understand that this drive to generate content that captures that momentary engagement that is the ‘like’ … it’s a losing battle because the engagement that you’re getting is so superficial and so momentary and so promiscuous that it’s not, in the long run, what you believe should be important, which is deeper engagement that generates loyalty and ultimately advocacy,” said Robert Triefus, chief executive of Stone Island and a former Gucci executive.

There are indications that dopamine culture may be peaking. The churn of microtrends has started to slow, while consumers are seeking out longer-form content that doesn’t immediately yield a quick high and requires more sustained attention or interaction. TikTok has been pushing creators to produce longer videos for the past couple years, and data shows videos that exceed one minute tend to perform better on the platform. Some research has found longer videos outperform on YouTube as well. Triefus has noticed fashion brands putting energy into platforms such as Reddit and Substack.

Gioia has written about the trend, stating that any dopamine trigger becomes less effective over time (known as anhedonia) and audiences may finally be rebelling. He’s predicted that a new Romanticism characterised by a rejection of technology and celebration of human feeling could soon emerge.

The question is whether customers and the brands targeting them can truly break free of their dopamine addiction. There will always be those groups that push back against prevailing currents, but they don’t always become the mainstream. Rebecca Rom-Frank, a senior strategist at trend-forecasting firm WGSN, said there has been an uptick in people seeking out longer-form content again, but she described that group as older “traditionalists.”

“More chronically online audiences tend to crave more chaotic content, which I would classify as TikTok videos, memes, brain-rot videos like really crazy, fast-paced cartoons or images that are just very chaotic,” she said.

Dopamine culture may simply be a reality of today’s fashion market, in which any brand hoping to achieve or maintain a level of scale is locked in a competition for attention, and not just with other brands but with news, memes and everything else. But if fashion labels reorient themselves too much around providing a fleeting high that fades in an instant, they shouldn’t expect customers to hang around once the buzz is gone.

Additional reporting by Yola Mzizi.