George Stevens Academy is in its first year of an official cell phone policy. Students put their phones in a classroom caddy (pictured) when they walk in the door, so that they are not distracted while learning. COURTESY OF CHRISSY BEARDSLEY ALLEN , GSA

THE PENINSULA—Dan Welch, a career educator and school administrator, began to see issues with the rise of student cell phone use in the mid-2000s.

The flip phones with limited texting and rudimentary pictures would, two decades later, evolve into the smart phones of today—an entire universe in a pocket-size screen offering 24/7 communication.

“I find, more and more, students get anxious about not being able to respond, or [have] a need for an immediate reaction,” said Welch, who last summer became the new head of school at George Stevens Academy. “It’s hard to disengage from that and focus on academics.”

Cell phones also perpetuate student conflict, Welch said. Over weekends, for example, “things couldn’t settle down” because of constant connectivity to classmates and social media. Come Monday, students had been “living the conflict for days on end.”

So where does that leave schools in how they manage student cell phones? All local high schools—GSA, Deer Isle-Stonington High School, and Blue Hill Harbor School—have flexible student cell phone policies that allow some use during the school day, but not during class time. The aim is to eliminate distraction from learning, while also teaching students when cell phone use is appropriate.

“I think it’s great for us to be thinking about [cell phones] as a community, as a society,” said Andrew Dillon, the head of Blue Hill Harbor School, who is also a teacher. Especially, he added, for “young people as they are growing up and living through these times.”

“Like anything, there’s a time and a place,” Welch said. “It’s about teaching students to use cell phones as a tool.”

What schools are doing—and why

Deer Isle-Stonington High School allows students to use cell phones during lunch, breaks or walking between classes.

“During learning time the phones should not be seen at all,” said DISHS principal Rebecca Gratz. “My message to them is to be present in learning. And you can’t be present if you are on your phone.”

This is a more “relaxed” policy than a few years ago, Gratz said, now in her second year as principal. Gratz said her goal is to reduce the distractions and “constant interruptions” cell phones bring. Part of the policy’s purpose is to help “eliminate gray areas,” so that the rules don’t become a battle for teachers, Gratz said. For example, wearing earbuds is not allowed during class—even in one ear.

“You cannot be fully present with one earbud in. Even if you think you are, you’re not,” Gratz said.

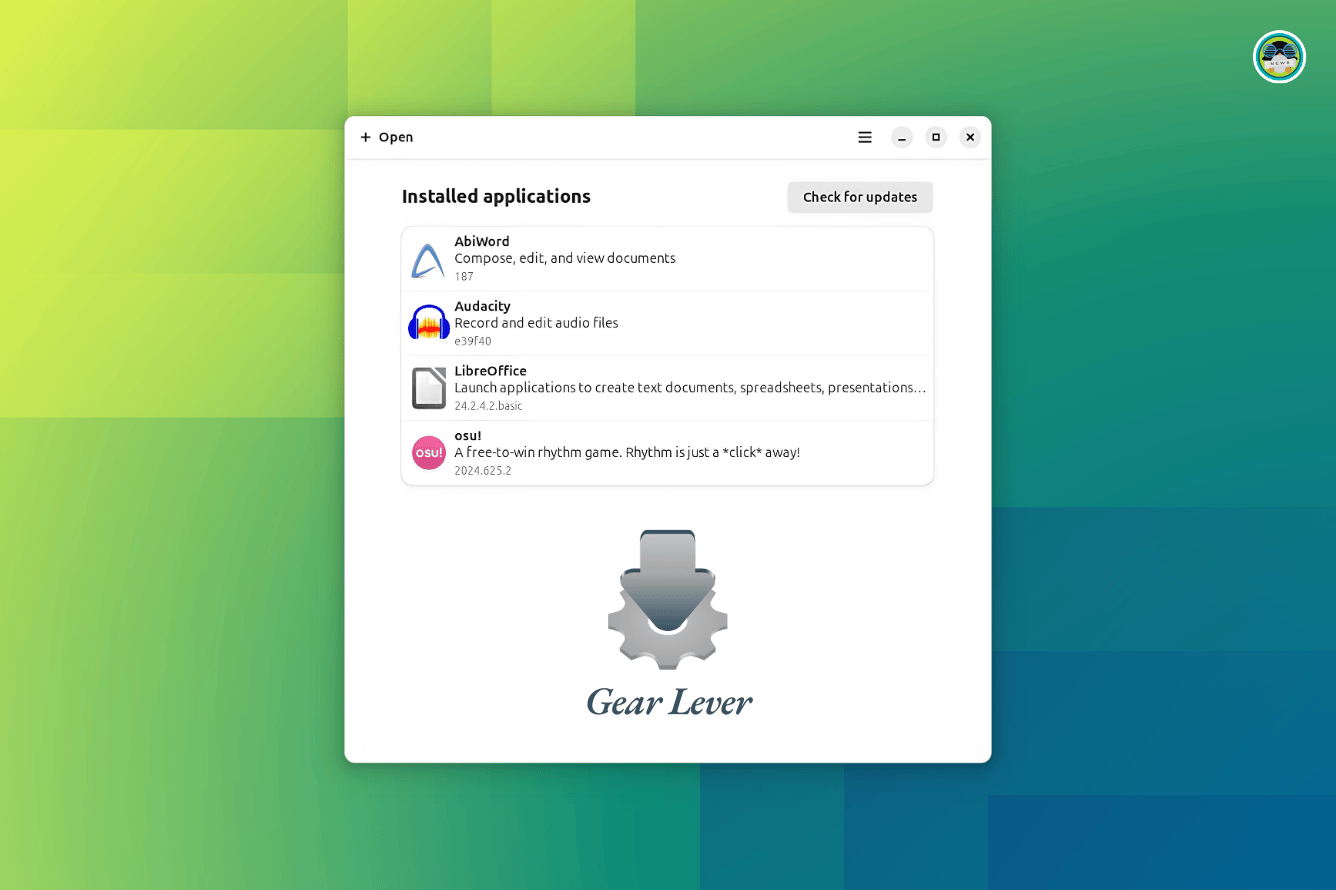

In Blue Hill, GSA is in its first year of having an official cell phone policy, said Dean of Student Life Chrissy Beardsley Allen.

“It’s a big shift for us,” she said.

During class, students must leave their cell phones in caddies by the door. They may use them during lunch and breaks, and while in the hallway. Beardsley Allen said the policy came about after feedback from teachers saying that the distraction of phones was impeding academics. Cell phones in class, she said, “were infringing on the rights of these students to learn.”

Welch said the new policy has created “uniformity” for both teachers and students to follow. At the same time, he said, allowing some access to phones during school and teaching appropriate use is important.

“I don’t feel a students’ school day should be so different from the rest of their life,” Welch said.

Dillon, the BHHS teacher and head of school, said cell phones are not a big issue during class at his school. Since the school is fairly small, when teachers ask students to put their phone away, they do, he said.

“If we see the problem, we can speak to students about it,” Dillon said. “It’s fairly cut and dried.”

Dillon said that during class, there are times when it is appropriate for a student to look up information on their phone. Similar to Gratz and Welch, he takes the approach that helping students know when and where to use phones is important.

“This is high school. They need to learn how to use their cell phones responsibly,” Dillon said.

Many of the local elementary and middle schools’ policies are much more restrictive. Sedgwick Elementary School and the Adams School in Castine require students to leave cell phones in the office until the end of the day. At Surry Elementary School, phones must be off and remain in a backpack or locker throughout the day.

“Cell phones are a detriment in schools, big time,” said Daniel Ormsby, principal at Blue Hill Consolidated School. There, the policy is for cell phones to be off, in a locker, and not out during the day. If seen, Ormsby said, the phone is taken.

Students as young as third grade have cell phones at BHCS, Ormsby said. By fifth grade, more kids have cell phones, and by seventh and eighth grade many students—but not all—are bringing them to school, he said.

Ormsby has been at BHSC for three years and said cell phones were one of the first issues he was asked to address. Kids are especially “susceptible” to being addicted to smart devices, he said, and teachers have had to change their lessons for kids’ shorter attention spans.

Ormsby said tablets and computers at BHCS are only for academic use. He would like the school to move away from educational games on devices as well.

But not all computer use is limited. BHCS is in the first phase of a three-year plan to get every middle level student a Chromebook for academic use. This year, all sixth graders received one, and Ormsby has heard positive feedback from students. The laptops make them “feel more adult and responsible,” he said.

BHCS now plans to use specialized lockers to limit cell phone use, a $5,000 cost approved by the school board in May. The lockers are small boxes, like a post office box, with an individual combination.

Once installed—the lockers are on back order now—dropping cell phones off will be the first thing students do each morning.

Student and parent response

Overall, educators interviewed said their respective cell phone policies are going well.

Beardsley Allen said that she’s “pleasantly surprised at how smooth the transition has been” at GSA. Many students, she said, are feeling relieved not to be socially “on” all the time, and having phones in a caddy during class is a “really great excuse” to not respond to messages immediately.

Ormsby said his no-phone policy at BHCS has been going great, with few violations. A big part of that, he said, is the staff being on board with the policy.

“That’s the biggest thing. If one staff member allows them, it’s a crack in the dam,” Ormsby said.

Parent buy-in is increasing as well. Part of that process means getting parents to stop texting their children during school hours.

“I can’t tell you how many times a student said, “Well, my mom is texting me.’ And I look and it is their mom,” Gratz said.

Both Gratz and Beardsley Allen said that, as parents, they are guilty of texting their kids during the school day.

“It’s hard for us as parents to respect those boundaries,” Gratz said. She added that overall parents at DISHS have been “super supportive” of the new procedures, including when a phone needs to be taken away from a student for misuse.

“I get it,” said Dillon about BHHS students communicating with parents and guardians during school. Often, they are communicating about things like health matters, and are looking for direct communication with their teenager, instead of going through the school. “A lot of times [the students] are using them responsibly to communicate in personal matters as an adult would,” Dillon said.

For resources on this topic, Dillon recommended Growing up in Public: Coming of Age in a Digital World by Devorah Heitner, on which Blue Hill Public Library offered a discussion series this past summer and fall.

Ormbsy said BHCS is organizing a book study for parents on The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, by Jonathan Haidt.