COLUMBIA, S.C. — When South Carolina students from kindergarten through high school return from their winter break, a big change will greet many of them.

Starting in January, every public school district in the state is required to start implementing a student cell phone ban, if they have not done so already.

Earlier this year, lawmakers included a temporary law in the current state budget, called a proviso, that directs school districts to craft and enforce a student cell phone policy by the second half of the 2024-2025 school year.

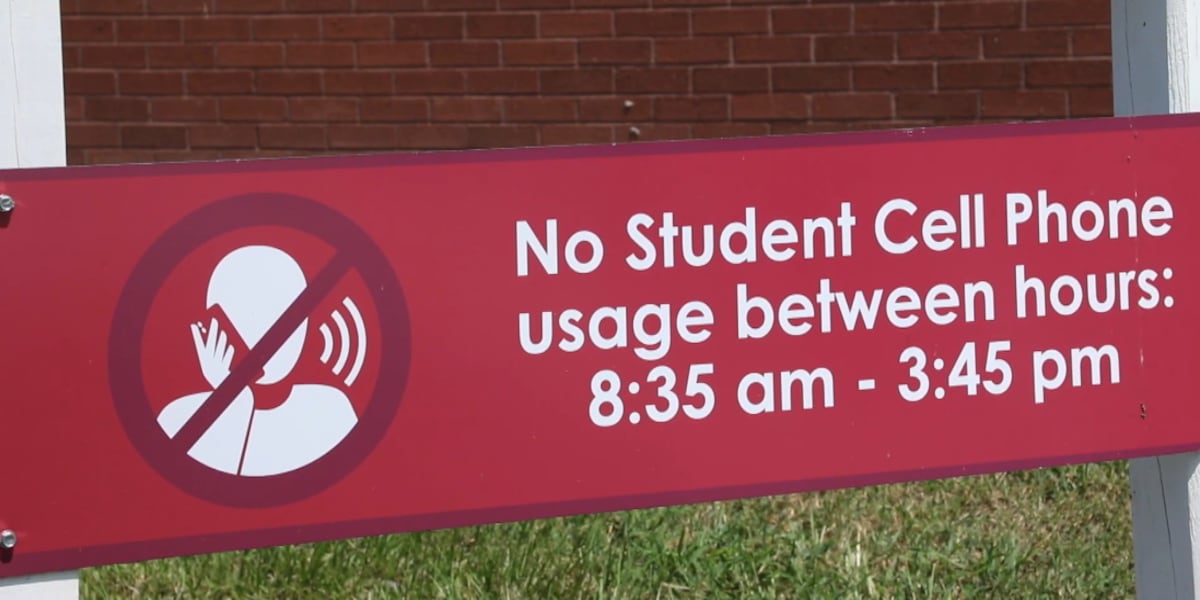

But months before that directive came from the State House, Rock Hill Schools put its own policy in place.

“Our educators were giving the feedback to our superintendent and our school board members that the cell phones were a real distraction in the classroom,” Lindsay Machak, Rock Hill’s Executive Director of Communications and Marketing, said.

So beginning in August of 2023, Rock Hill Schools told students from the morning bell to the afternoon dismissal bell, their phones had to be turned off and put away.

“There was that angst, that anxiety, and feelings of dismay over change. But once we really got it rolling, it was fine,” Machak said.

Rock Hill’s policy is essentially the rule students across South Carolina will have to follow, starting in January: No access to devices during the school day.

That includes cell phones, smart watches, tablets, and gaming devices, with very limited exceptions, like permission for use in learning.

“What we know we’re doing here is giving students the freedom to focus. It’s the gift of focus, as opposed to something we’re taking away,” State Superintendent of Education Ellen Weaver, a chief proponent of this measure, said.

This fall, the State Board of Education adopted a model policy with those bell-to-bell restrictions, and every district’s policy had to be at least as strict as the state’s.

Exceptions would be allowed for students with IEPs and medical plans if the device is needed for medical or educational purposes, as well as for students who serve as volunteer firefighters or in other emergency organizations, with permission from their district superintendent.

Some school districts might opt for even stricter measures or put their own restrictions on students having their phones on buses or at afterschool activities.

They are also allowed to decide what the consequences are for students who break the rule.

“We’ve encouraged districts all along to try to look at policies that remove the phone from the situation and not the student from the classroom,” Weaver said. “And so what we’re going to see over the next four or five months of the second semester as this is implemented in January, what’s working and what’s not working. And so we’re going to take a very close look at evaluating implementation and be able to make additional recommendations to districts to fine-tune their policies after that.”

With their policy now in place for three semesters, Rock Hill leaders attest it has sparked changes in behavior.

“Coming out of the pandemic, you saw a lot of kids who were on devices, on their phones, not really talking to one another,” Machak said. “But now, you go out to one of our high schools during class exchange or during lunch periods, or you see kids reconnecting over books, reading books, or having conversations.”

Districts that fail to adopt and adhere to a local cell phone policy could put their state funding at risk.

Weaver said the Department of Education will be in communication with districts and teachers to ensure these policies are actually being enforced.

Feel more informed, prepared, and connected with WIS. For more free content like this, subscribe to our email newsletter, and download our apps. Have feedback that can help us improve? Click here.

Copyright 2024 WIS. All rights reserved.