Barbara Rae-Venter, a 76-year-old patent attorney living in Marina, California, thought she’d spend her retirement leisurely playing tennis, traveling, and indulging in her favorite pastime: researching her ancestry and building a family tree. It didn’t quite work out that way. For Rae-Venter, something she started as a hobby led to capturing one of the most notorious criminals in California.

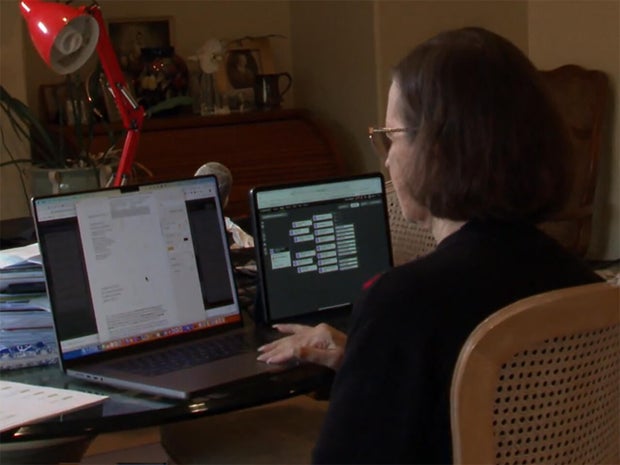

Seven years ago, Rae-Venter, using her genetic research skills, tracked down a fugitive in California who had eluded capture for more than three decades, and remarkably, she did it without ever leaving her home.

The fugitive was the Golden State Killer. In April 2018, the FBI and California law enforcement made headlines with a stunning announcement: “We found the needle in the haystack, and it was right here in Sacramento.”

Since 1974, investigators had sought the man responsible for at least 13 murders and more than 50 rapes in the state of California. But it wasn’t until Rae-Venter joined the investigation that they learned his name: Joseph James DeAngelo. “It’s not that I’m so very special,” said Rae-Venter. “It’s just I happened to be in the right place at the right time.”

Using DNA left by DeAngelo at a crime scene, Rae-Venter identified him by using a technique now known as investigative genetic genealogy. “It’s just basically doing the same as you would do if you’re doing family history research, and augmenting that with DNA to make sure that the relatives that you find are really related to you,” she said.

Her crime-solving career began quite by accident. Rae-Venter, who also has a Ph.D. in biology, was volunteering as a search angel – a person who helps adoptees find their biological parents. “It’s such a fundamental desire,” she said. “They’re just so focused. They just so want to know where they came from.”

A Living Jane Doe

In 2015, Rae-Venter responded to an email sent by Peter Headley, then a veteran investigator with the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, and fell into her first mystery. Headley was trying to uncover the true identity of a woman in her 30s who had been kidnapped as a child. “She really wanted to know who she was,” said Headley, referring to her as a living Jane Doe. “She’s alive, but we have no idea who she is,” he said.

That living “Jane Doe” went by the name of Lisa Jenson. At five years old, she had been abandoned at an RV park by a man called Gordon Jenson. “It turned out she had been kidnapped by the suspect, and he just told everyone that he was her father,” Headley said.

Later, detectives learned that Gordon Jenson was just one of many aliases used by Terry Rasmussen, a notorious serial killer, who died in prison in 2010 without ever revealing who Lisa really was.

Lisa Jenson did not know who her mother was, or if she had any sisters or brothers. Headley said that Lisa had heard about genetic genealogy and wondered if that could lead her to her real family: “I said, ‘Okay, let’s try it.’ So, opened an account for her, got her in Ancestry, and we had some distant matches, and I’m like, this might just work.”

But this was new territory for Headley, so he emailed DNA Adoption for help and found Barbara Rae-Venter. Asked why she agreed to collaborate, Rae-Venter replied, “It was a puzzle!”

She began the laborious process of building family trees to find Lisa’s real family, which involved more than just looking at DNA: “The DNA is just the jump-off point. You’re doing census records, you’re doing birth, death and marriage records. My favorite is probably Facebook. I’ve actually built trees from the amount of stuff people have put in their Facebook pages.”

CBS News

Headley helped by coaxing distant relatives to take DNA tests. “People were skeptical, thought it was a scam,” he said. “One lady thought I was going to clone her.”

And DNA tests are expensive. Headley and Rae-Venter reached into their own pockets to help subsidize the costs.

I asked, “So, you’re not only not getting paid to do this work, you’re actually paying for these tests?”

“We probably each spent a couple of thousand dollars on kits,” Rae-Venter said.

It took nearly a year, but in 2016, the DNA trail led to New Hampshire, and the case of a missing young mother, Denise Beaudin. She and her infant daughter had vanished from her home, along with a man named Bob Evans, which turned out to be yet another alias of that serial killer, Terry Rasmussen

Investigators believe Rasmussen killed Denise and kidnapped her little girl. For the first time, Lisa Jenson was about to learn her real name: Dawn Beaudin.

Headley said, “I called Lisa up and I asked her if she wanted to know her real name, we had figured it out. And she just got real quiet, and very quietly said yes.”

Lisa has asked for privacy, but, in a phone call told Rae-Venter that she could finally move on in her life, including getting married.

“She just said it didn’t feel right when she didn’t really know who she was or where she’d come from,” said Rae-Venter. “And now that she knew that, she felt comfortable now going forward and getting married. I just thought that was so special.”

Building the Family Tree of a Killer

It was one of the first times that genetic genealogy was used to solve a criminal case – and word spread fast. In 2017, Rae-Venter got a call: Could she use the same technique to find the Golden State Killer? At the time, there were six full-time investigators and three FBI agents on the case, and they couldn’t find him. Rae-Venter thought the DNA would tell her who he was. “I was absolutely certain of that,” she said.

Investigators provided a DNA profile left at a California crime scene, and Rae-Venter uploaded it to GED Match and Family Tree DNA. This time, she was building the family tree of a killer.

CBS News

Sixty-three days later, she said, “I’m sitting there at three in the morning all by my little lonesome staring at my computer. I know who you are: You’re Joseph DeAngelo.”

I asked, “At that moment, were you the only person in the world who knew who the Golden State Killer was?”

“Besides him? Probably,” Rae-Venter replied.

It was an astonishing breakthrough. But Rae-Venter’s word was not enough to make an arrest. “I’m providing an investigative lead. You still need some old-fashioned detective work,” she said.

So investigators got to work getting a DNA sample from DeAngelo himself to confirm he was the right guy. Within days, the brutal killer who had evaded law enforcement for decades was finally behind bars.

In 2020, DeAngelo was sentenced to 13 consecutive life sentences. After DeAngelo was locked away, Rae-Venter decided that it was time to share her incredible story in a book, “I Know Who You Are.” She has been profiled in The New York Times, and appeared on Time Magazine’s list of the most influential people.

And she’s come out of retirement. Her group, Firebird Forensics, works with law enforcement agencies nationwide to solve cases using genetic genealogy, and has solved approximately 60 cases. She even travels around the country teaching others her technique.

In 2023 she described the process of using genetic genealogy as “very addictive, because you know you’re hot on the trail and you just know if you just keep going a little bit longer, you’re going to find the connections you’re looking for.”

But her line of work has also raised concerns about privacy. More than 53 million people have already uploaded their DNA profiles to public databases. Should police be able to use that information to track down the users’ criminal relatives? “Well, unfortunately, I think that horse left the barn a long time ago,” Rae-Venter said.

And the trade-off may be worth it, says Rae-Venter and others, if it means getting killers and rapists off the streets. Michael O’Malley, the prosecuting attorney in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, said, “There was a lot of light bulbs going off across the country saying, ‘What great technology! How do we bring it to our community to solve violent crimes?'”

Watch Part Two of Erin Moriarty’s report:

Who is John Doe #147?

O’Malley is a witness to a sad statistic in this country: more and more serious crimes are going unsolved. “I get violent crime reports that come across my desk every day, and only a fraction of those are solved,” he said.

In 2020, O’Malley’s office set up the G.O.L.D. Unit, a team of prosecutors who use the latest forensic tools to find criminals and get them off the streets. It’s run by supervising assistant prosecuting attorney Mary Weston. “We review cases, mostly sexual assaults and homicides at this time, that can be re-investigated using perhaps updated technologies,” she said.

Among them, cases involving sexual predators, like John Doe #147. “That’s all we knew him as,” said Weston.

On a hot afternoon in August 1997, a man grabbed a nine-year-old boy in the woods behind a school in the Cleveland suburbs, and sexually assaulted him.

The nine-year-old victim is now a thirty-seven-year old man, who asked us to call him “Michael,” and not show his face. Describing the years since the assault, he said, “It’s just been a lot of ups-and-downs, you know? I had doubts, thinking, ‘Would I ever, would we ever find the guy?’

“I remember running to my dad, him taking me to the hospital,” Michael said. “But the most I could remember is my mom. She was just crying hysterically on the front porch, just blaming herself, and the neighbors are trying to calm her down.”

Investigators knew little about the predator back in 1997, according to O’Malley: “The young boy gave a description, roughly, of his age, and his body build. But really that was it,” he said.

There was DNA left on the child’s clothing. In 2003, a profile was submitted to the federal database (known as CODIS), which contains DNA profiles of convicted offenders. There was no match. So, investigators had a DNA profile, but not a name to go with it.

“I was crushed,” said Michael. “I think, my only hope is just gone. He’s gonna actually get away with it.”

To stop the statute of limitations for rape from running out, “John Doe #147” was indicted, but with no leads, the case went cold. Weston said, “At the time, you know, we were at a loss. What are we gonna do for this boy? He’s not a boy anymore, but what can we do to try to help solve his case?”

Michael said he was scared that the predator might find him again: “Oh, yeah, I always thought, ‘Could this guy be watching?’ And he threatened to kill me if I had told anybody about the horrible incident.”

But in 2018, Michael – and the rest of the world – watched the Golden State Killer case play out on TV. “And it was like a lightbulb lit above my head,” he said. “I’m like, ‘Oh, there’s another way.'”

The capture of notorious serial killer James James DeAngelo introduced the world to investigative genetic genealogy. Could that same technique help solve Michael’s case? Investigators would need a more complete profile of the rapist’s DNA. But again, there was a hitch: when investigators went looking for the rape kit from Michael’s case, they discovered that it had been destroyed.

“I’m not your victim anymore”

But investigators didn’t give up, and got a stroke of luck when a key piece of evidence was discovered at the county’s crime laboratory: an original tube used for testing that could have some leftover DNA. “I was very, very excited,” said Weston. “But then there’s the waiting. Is it gonna be enough? And then, ‘Are you gonna be able to work with this very tiny amount of DNA?’ It’s nine nanograms.”

Astoundingly, it was enough, and in March 2022, they turned to someone familiar: Barbara Rae-Venter, the genealogist who tracked down the Golden State Killer. “If I had faith in anybody to do it, it was her,” said Weston. “She had solved a few cases for us already, and I knew this case was in good hands.”

It took two months. Rae-Venter came up with a list of suspects, all brothers. Ohio investigators then were able to narrow that list down to just one, and asked Michael to view a photo lineup. “Immediately, you know, my heart started pounding,” he said. “I started getting clammy and sweaty, sorta like a flashback, you know, to when I seen him standing there in the woods.”

The man he recognized was Dennis Gribble, an Ohio resident with a long history of sex crimes. It was all investigators needed to get a search warrant. Days later, they appeared on Gribble’s doorstep to get a DNA sample, telling him, “Please open your mouth.”

What was his reaction? “He was stunned, but he complied,” O’Malley said. “And we took it back to our lab and confirmed that he was the individual who sexually assaulted Michael back in 1997.”

And that’s how, in May 2023, John Doe #147, now identified as Dennis Gribble, appeared in an orange jumpsuit and handcuffs in a Cleveland courtroom. Michael was there. He looked at Gribble (“I was just disgusted”), and read an impact statement to the court: “I have learned to be a better person and a father than the monster you are and will always be.”

Michael said, “I wanted to show him he didn’t get the best of me. I’m not your victim anymore. I’m not somebody you prey on anymore.”

Gribble, now 75, pleaded guilty to one count of rape, and is currently serving 10 years in prison.

With a federal grant to help cover the costs of testing, the G.O.L.D. Unit has now helped solve 13 rape cases in the Cleveland area, with Barbara Rae-Venter’s help. Yet, neither O’Malley nor Weston has ever met Rae-Venter. “We Zoom!” Weston laughed.

I asked, “Is that a little odd, that you’re working with this investigator who really never leaves her dining room table? That’s where she does all her investigations.”

“I hope she never leaves it again!” O’Malley laughed.

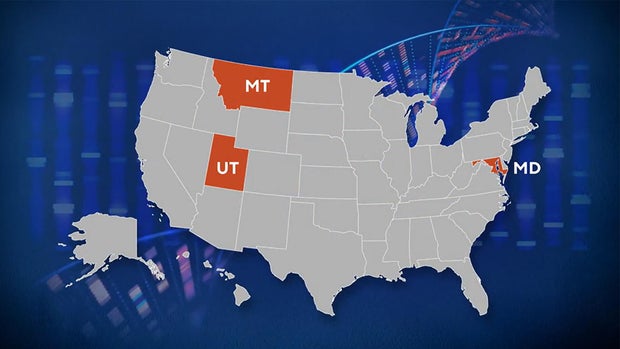

The technique that Rae-Venter used to track down Dennis Gribble has been used to identify other elusive criminals, including Bryan Kohberger, who earlier this month pleaded guilty to killing four University of Idaho students in 2022.

O’Malley says he believes genetic genealogy will someday solve less serious offenses as well. “Right now, it’s still a very expensive tool, and it takes a lot of time,” he said. “But I do see it expanding in the future.”

Still, as the field expands, so have privacy concerns. Some states have set limits, although there are no national laws restricting the use of genetic genealogy by law enforcement.

CBS News

And for victims like Michael, the benefits outweigh the risks. Genetic genealogy was his only chance for justice. “It was a needle in a haystack,” he said. “The guy would have got away scot-free. Had it not been for DNA and genealogy, I would have never been here today. We wouldn’t even be talking about it.”

For more info:

Produced by Michelle Kessel. Editor: George Pozderec.

See also: