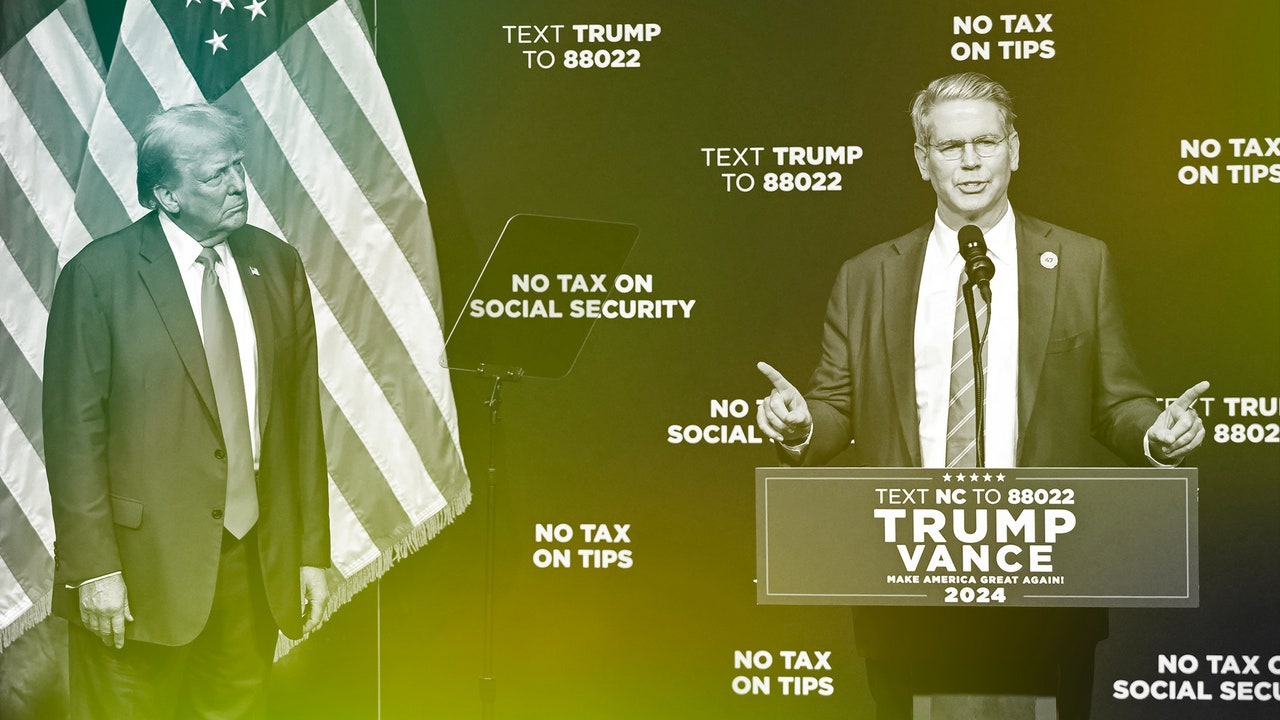

Give Donald Trump credit for this: he can turn practically anything into a reality show, including picking a Treasury Secretary. The media had followed the selection process on a daily, and sometimes hourly, basis as Trump auditioned a number of candidates in recent weeks for the top economic post in his second Administration. On Friday, the “Apprentice”-style bake-off ended with him choosing Scott Bessent, a sixty-two-year-old hedge-fund manager who, though reasonably well-known in financial circles, has virtually no public profile. Earlier this year, Trump described Bessent as “one of the most brilliant minds on Wall Street,” but his candidacy for the Treasury post ran into opposition from some of the President-elect’s associates, including Elon Musk.

The choice of Bessent is interesting for a number of reasons, including his personal background. He was once a Democratic donor: this past weekend, the New York Times published a photograph of him co-hosting a Democratic fund-raiser attended by Al Gore at Bessent’s Hamptons home during the 2000 Presidential campaign. He spent many years working for Soros Fund Management, the investment firm owned by the Democratic mega-donor George Soros. And, if he makes it through Senate confirmation, he would be the first openly gay Treasury Secretary.

Although Bessent describes himself as a “data person,” he is also a free-market conservative. Earlier this year, he emerged as a prominent supporter of and adviser to Trump. Bessent donated to his campaign and helped organize fund-raisers for him in New York and London. When I interviewed Bessent in June, he strongly criticized the Biden Administration’s spending and regulatory policies, and defended Trump’s economic agenda. Pointing to the organized nature of the Trump 2024 campaign, he suggested that a second Trump Administration would operate more smoothly than the first one.

That remains to be seen, but whatever happens Bessent will be in the thick of it. Given that his soon-to-be boss is famously obsessed with the stock market, he will be tasked with selling to investors an economic agenda including mass deportations that could lead to labor shortages, tax cuts that would add to an already gaping budget deficit, and blanket tariffs on imported goods that could well lead to another round of sticker shock for American consumers.

Last week, major retailers warned that if Trump goes ahead and imposes tariffs—he’s talked about levies of up to twenty per cent on most imported goods, and sixty per cent on goods sourced from China—they will be forced to raise their prices. A Walmart spokesperson said, in a statement, “We’re concerned that significantly increased tariffs could lead to increased costs for our customers at a time when they are still feeling the remnants of inflation.” Philip Daniele, the chief executive of the car-parts company AutoZone, said bluntly, on an earnings call, “If we get tariffs, we will pass those tariff costs back to the consumer.”

Many people in corporate America and on Wall Street will be hoping that Bessent exerts a moderating influence on trade policy. In an interview with the Financial Times shortly before the election, he appeared to suggest that Trump’s tough talk was largely a negotiating tactic. “My general view is that at the end of the day, he’s a free trader,” he said. “It’s escalate to de-escalate.” After Trump won, however, Bessent published an article on FoxNews.com, in which he advocated for tariffs, saying they could be used to raise revenues for the federal government, encourage businesses to shift production to the United States, and “reduce our reliance on industrial production from strategic rivals.”

Bessent’s views on trade policy aren’t entirely clear, and neither is the amount of influence he will actually exert in this area. Normally, such policy is the prerogative of the U.S. Trade Representative, who operates under the auspices of the executive office of the President, not the Treasury Department. In the first Trump Administration, the Trade Representative was Robert Lighthizer, a veteran corporate lawyer who commissioned a detailed report about China’s mercantilist trade policies, which the Administration then used as a justification for imposing tariffs. Shortly after the election, the Wall Street Journal reported that Trump had told allies he wanted Lighthizer to serve as his “trade czar” during his second term. But, as yet, the President-elect hasn’t appointed Lighthizer to any position, or picked someone else for the post of Trade Representative.

Adding even more murk to the water, last week, when Trump selected Howard Lutnick, the chief executive of the Wall Street firm Cantor Fitzgerald, as his Secretary of Commerce, he said that Lutnick will have “additional direct responsibility” for the office of the Trade Representative. Lutnick and Bessent have a history—a very recent one. According to numerous accounts, Lutnick, who is a co-chair of Trump’s transition, was one of the actors who tried to block Bessent’s appointment to the Treasury Department. A report in the Wall Street Journal described the internal battle between the two men as a “knife fight.” Bessent’s opponents, in an effort to discredit him, suggested he wasn’t a true believer in protectionism and reminded Trump about Bessent’s time working for Soros, the Journal said.

Bessent joined Soros Fund Management in 1991 and stayed there until 2000. In 1992, he was part of the Soros team that made a famous speculative bet against the pound sterling, which caused the currency to crash and Britain to tumble out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. (According to news accounts, the trade netted the Soros outfit at least a billion dollars in profit.) For some years, Bessent ran his own hedge fund. In 2011, he returned to Soros Fund Management as chief investment officer. After leaving for a second time, in 2015, he set up another hedge fund, Key Square, in which Soros was one of the major investors.

Trump hasn’t commented on Bessent’s historical ties to Soros. In picking him, he seems to have taken the view, common on Wall Street, that making money and engaging in politics are two separate enterprises, which shouldn’t be allowed to come into conflict. (Stanley Druckenmiller, another former associate of Soros, has supported Republican candidates, including Tim Scott and Nikki Haley in the 2024 G.O.P. Presidential primary.) Bessent, for his part, has cultivated connections in MAGA circles. He is reportedly close to J. D. Vance. Steve Bannon and Roger Stone expressed support for him getting the Treasury job.

In office, he will likely be confronted by the same sort of turf wars and political jockeying that characterized the first Trump Administration, and which Trump sometimes seems to relish. (Will he make Bessent and Lutnick sit next to each other at Cabinet meetings?) A larger challenge will come in trying to rationalize—or gloss over—the many contradictions in Trump’s plutocratic populism. The President-elect is promising to help out the working class by cutting taxes on major corporations and his fellow-billionaires. He’ll fix the deficit by slashing government revenues. He’ll bring down prices by introducing tariffs that raise them.

Moreover, some of Trump’s major policy planks may well clash with each other. He says his tariffs will bring down the trade deficit and make America more self-sufficient. But the combination of blanket tariffs, mass deportations, and tax cuts could well prompt a Federal Reserve that is still fearful of inflation to keep interest rates higher, which would boost the value of the dollar and make American goods less competitive abroad. That, in turn, would tend to increase the trade deficit.