Planet China: Thirteenth in a series about how Beijing’s trillion-dollar development plan is reshaping the globe—and the natural world.

LIMÓN INDANZA, Ecuador—Long drifts of mist settle between the mountain peaks in this region, almost indistinguishable from clouds. Underneath, species found only here depend on the intricacies of this high-altitude rainforest, one of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

Like many parts of the Amazon, this fragile and abundant wilderness is imperiled—and not only by the usual dangers of development and climate change. Mounting sovereign debt has become one of the Ecuadorian Amazon’s biggest threats, pushing the government to expand oil and mining to keep public finances afloat.

Ecuador owes $49 billion to foreign creditors and is paying billions more just to service the debt that instead could be spent on urgently needed environmental protections.

But today, an effort is underway that could transform this liability into a tool for conservation. In 2024, through a deal known as a debt-for-nature swap, the Ecuadorian government was able to refinance some of its costliest, privately held debt for pennies on the dollar and replace it with a lower-interest, longer-maturity bond. In return, Ecuador agreed to expand protections across its Amazonian region, which spans about half the country.

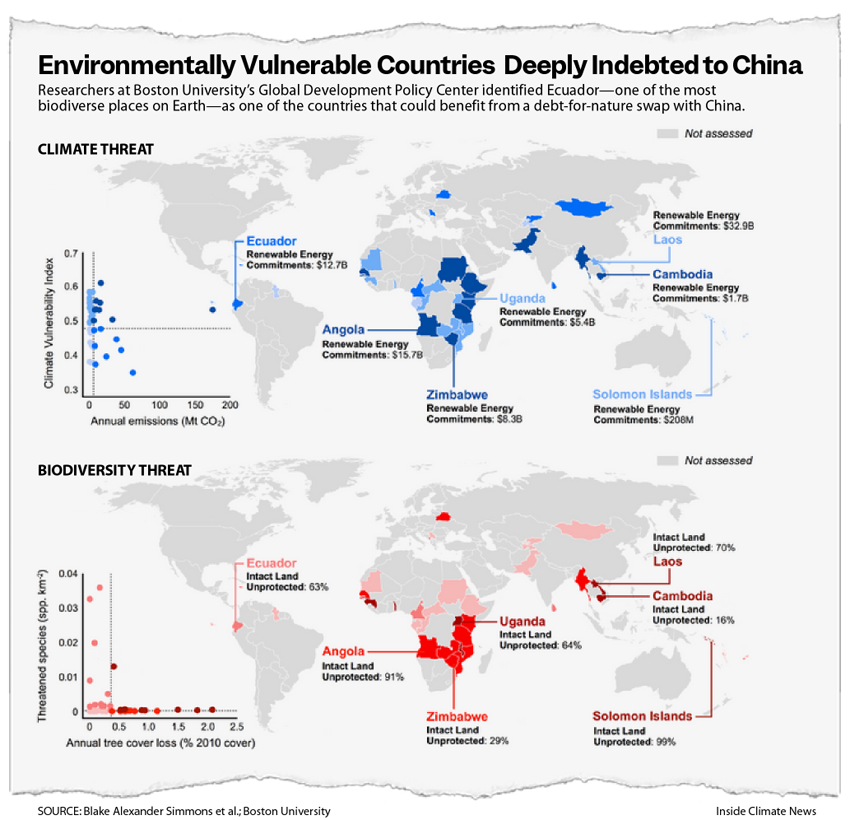

Debt swaps—for nature, development projects and more—are not new. Western creditors have been experimenting with versions of them since the 1980s. In recent years, countries such as Seychelles and Barbados have executed deals with private creditors like commercial banks, mobilizing hundreds of millions of dollars for conservation. Now, a small chorus of academics and policy thinkers is looking beyond traditional lenders to one with massive and untapped leverage: China.

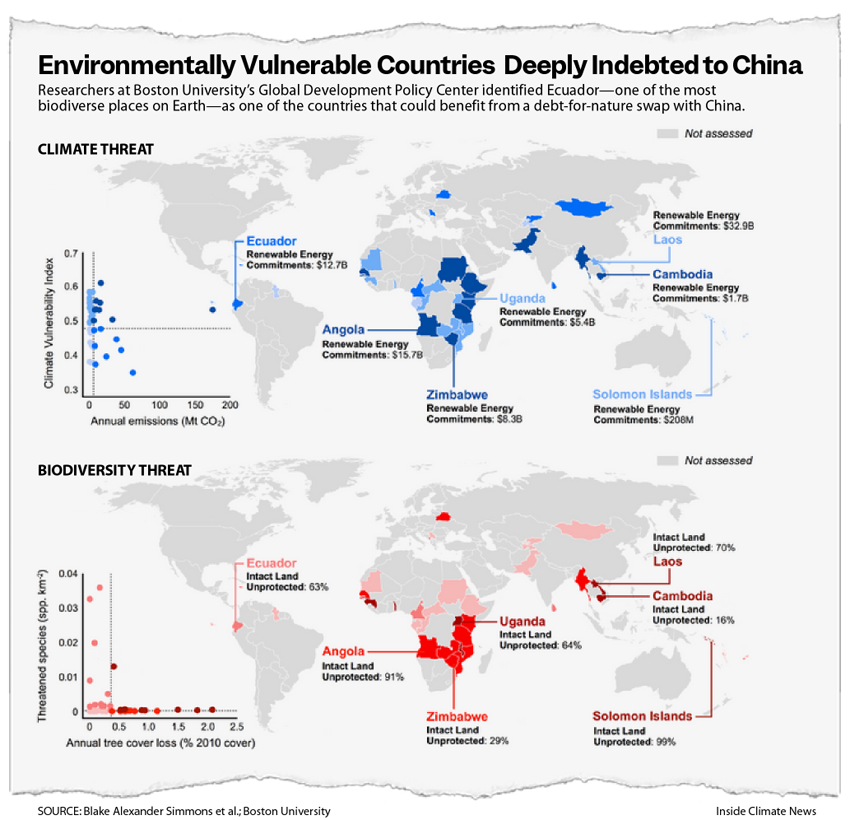

Through its $1.3 trillion Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has become the world’s largest bilateral creditor by financing mines, ports, power plants and infrastructure in countries across the developing world. China’s opaque lending practices make it difficult to know exactly how much these countries owe, but experts say it could exceed hundreds of billions of dollars.

Those massive figures caught the attention of economist and China expert Christoph Nedopil Wang, who was among the first researchers to see an opportunity in them. In 2021, he and his colleagues wrote a paper advancing the idea that China could help countries redirect some of that debt into conservation efforts.

China took notice. The central bank’s Green Finance Committee commissioned Nedopil Wang to do a special study on the topic, as did the United Nations Development Programme. And while Beijing has yet to do a debt-for-nature deal, it’s discussing another form of debt swap with Egypt and other increasingly sophisticated financial transactions to alleviate debt.

Rebecca Ray, an economist at Boston University who is among the pioneering thinkers on China and debt swaps, argues such new approaches are overdue. “One cyclone can wipe out multiple years of export earnings, and that kind of climate shock is making debt crises more common,” she said.

China’s Belt and Road spending spree has unlocked development funding for cash-strapped countries like Ecuador but has also left behind a trail of environmental destruction while contributing to ballooning debt burdens further strained by rising interest rates and the COVID-19 pandemic.

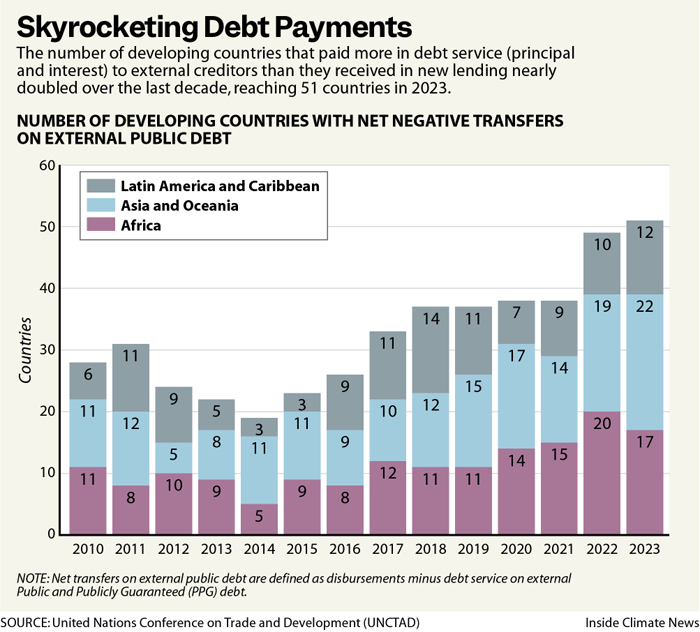

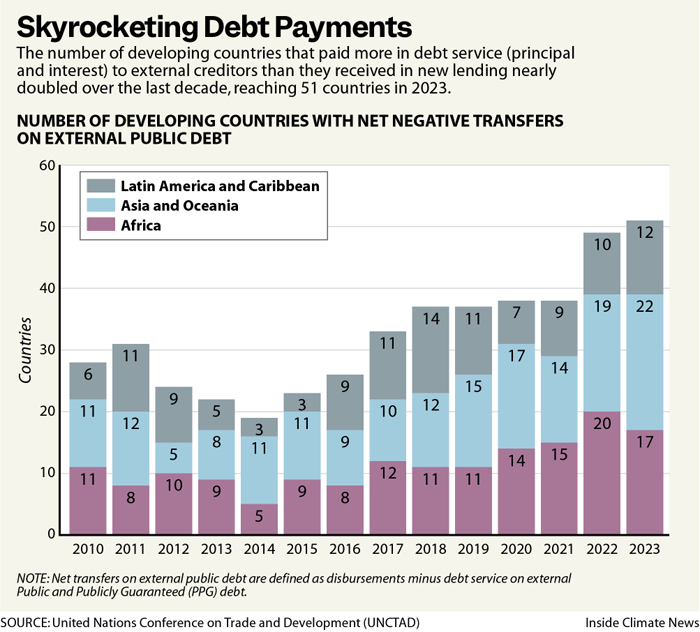

Today, the world’s poorest countries, many of which owe debt to China, spend twice as much servicing debt as they receive in climate funding. Unless debt burdens ease, the financial pressure on those countries could drive them toward greater resource extraction, further imperiling some of the most critical ecosystems on Earth.

Supporters of Chinese participation in debt-for-nature swaps say the model offers a way to relieve some of that burden while redirecting Beijing’s influence toward repairing the landscapes its projects damaged.

Proponents view these deals as win-wins, but some environmental economists and scholars remain deeply skeptical. They note Beijing’s reluctance to write off debt for fear of triggering demands for similar treatment from other borrowers, and say other creditors like multilateral development banks and private debt holders—which, collectively, hold the majority of most developing countries’ external debt—should be first in line to take a loss.

“China feels, from its perspective, ‘Why should we be the ones?’” said Elizabeth Losos, executive in residence at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability. “They don’t want to set a precedent.”

The flip side, she noted, is that China is carrying a portfolio of borrowers that aren’t able to pay back their debts on time. Many have been forced to roll over their loans, reducing the debt’s ultimate value. In that context, accepting an immediate payment rather than uncertain payments in the future—while also accruing geopolitical goodwill at a moment when the United States is retreating from climate and environmental cooperation—may be the more strategic choice, Losos said.

For now, China’s willingness to use its financial clout for conservation or other sustainable development goals remains uncertain. Even if Beijing were to embrace debt swaps more broadly, its environmental legacy across many Belt and Road countries raises doubts.

In Ecuador, Chinese firms have dammed rivers, mined mountains and drilled pristine rainforest. That track record makes it hard for many Ecuadorians to imagine China as a sudden champion of global conservation.

Julio Prieto, a Quito-based environmental lawyer, recently sued a Chinese firm over a sprawling waste pit at one of its mines. Along with civil society groups, Prieto has criticized Chinese companies for steamrolling over local objections in communities where it has built major projects. He questions China’s will to establish a complex conservation deal that would respect human rights.

“If the Chinese government and Chinese companies are not willing to be transparent about something as basic as their construction plans,” Prieto said, “I’d be surprised if they were open to taking a fundamentally different approach on debt swaps.”

Leaning In

When Nedopil Wang first contemplated a China-backed debt swap, the reaction from many China watchers at the time was dismissive: “‘OK, you’re crazy. What even is this?’” he recalled them saying.

Beijing’s interest was clearly piqued. The powerful Ministry of Commerce, responsible for overseas development assistance, conducted its own research and Chinese officials began showing up to Nedopil Wang’s presentations. Yet, what the Communist Party’s top leadership ultimately thinks of those ideas remains unknowable.

“It’s a fantastically closed system,” Nedopil Wang said.

China’s embassy in Washington, D.C. declined to comment for this story, referring Inside Climate News to various Chinese ministries. The China International Development Cooperation Agency in turn suggested the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, which along with the Ministry of Natural Resources and the National Development and Reform Commission did not respond. China’s embassy in Ecuador also did not respond to requests for comment.

But China’s debt-swap discussion with Egypt suggests Beijing is at least interested in testing the idea.

In 2023, the countries opened negotiations to swap some of Cairo’s $8 billion debt to China for interest-free loans financing a broad sweep of projects, including renewable energy and healthcare development. Ray calls this trial run “China’s proof of concept.”

Nedopil Wang explained that Egypt approached China and said, “Here’s an opportunity for you as a creditor to support our development through swaps.” he said the details of the deal are still unclear. “It remains to be seen how it’s going to be applied, but it seems the focus is on interest-free debt,” he added.

Negotiators rarely disclose details of debt swaps in advance because any information surrounding a possible deal could influence financial markets. But policy analysts have identified a slate of countries as strong candidates for Chinese debt restructuring.

Pakistan is a key example. China has become its largest creditor after kicking off a massive project known as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. One of the central pillars of the Belt and Road Initiative, it aims to secure road and water routes from western China to the Middle East and has fast-tracked the construction of seven coal-fired power plants, with another planned. Pakistan owes China just under $30 billion—more than any other country.

“Pakistan has such a high debt level where China plays such a big, big role, and there are multiple underperforming assets that make the debt payment sometimes difficult,” Nedopil Wang explained. “There’s also a huge opportunity to do … a debt-for-renewables swap in this case. So I think this is a space to watch.”

The Chinese-backed coal plants there have underperformed because of lower demand from consumers, making it more difficult for Pakistan to repay the debt. Under a debt-for-renewables swap, in theory, Pakistan and China would agree to refinance coal plants with lower interest and retire them earlier than planned with a promise by Pakistan to move toward a greater percentage of renewables to meet demand. That would reduce the risk of default for Chinese creditors, Nedopil Wang said, while accelerating Pakistan’s transition to renewable and cheaper sources of energy.

“You have loans at risk of non-performance, and a bank might want to get rid of them. Rather than having to write those loans down, a bank can get rid of them at 70 percent and thus actually make money,” Nedopil Wang said, noting that, in the case of a swap, the plants would still operate, but for a shorter period of time, providing revenue to pay back the new lower-priced debt.

An official at one of the country’s primary business lobbies recently urged the government to seek debt-for-nature swaps with China as the two countries discuss debt relief. And Aneel Salman, chair of economic security at the Islamabad Policy Research Institute, noted that the country’s new sustainable financing framework explicitly says the government could consider the swaps as part of a blended finance deal. Pakistan’s finance minister has been actively talking about debt-for-nature swaps in public addresses, he added.

“We have shown our eagerness,” Salman said.

Ray also noted that a debt swap could be used to help the flood-prone country adapt to increasingly extreme weather.

A swap in Mongolia, meanwhile, would offer an unique opportunity for reforestation along the Chinese border to mitigate the sandstorms that blow into Beijing, Nedopil Wang said.

If China does pursue these swaps, it would join a growing trend. Countries have struck at least 10 debt-for-nature deals in recent years as climate change-induced extreme weather and the pandemic worsened the debt load in lower-income countries already struggling to pay back loans. In 2024, external debt in lower-income countries hit a record high of $8.9 trillion, while around 88 percent of the world’s most endangered ecosystems lie in debt-distressed nations.

Even the most ardent proponents of swaps don’t see them as a complete fix. They won’t close the world’s $700 billion annual financing shortfall for conserving biodiversity, nor the roughly $4 trillion gap for achieving the U.N.’s sustainable development goals, including greater access to clean energy and less poverty. But advocates argue they can meaningfully chip away at these problems by converting financial distress into public benefits.

The model could be particularly promising in parts of Africa, where Chinese companies have spent the past two decades mining the minerals that power the global renewable-energy transition, said Jean-Marc Malambwe Kilolo, an economist with the U.N. Economic Commission for Africa who has advised governments on debt-swap proposals.

Many African countries want to move beyond extraction and into higher-value refining and manufacturing for technologies like electric vehicles, he said. Well-designed debt-for-development swaps could support that shift while also benefiting local communities.

With roughly 43 percent of Africans lacking access to electricity, many households rely on firewood and charcoal for cooking and heat. “People need to be incentivized not to cut trees—to preserve and conserve green spaces,” Malambwe Kilolo said. “If there is no economic benefit, then what’s the point of doing conservation?”

In Ecuador, the same needs—and incentives—could translate to conservation.

“Our Currency Is Our Biodiversity”

On a bright November afternoon, perched above the narrow streets of Cuenca, former Ecuadorian environment and foreign affairs minister Gustavo Manrique Miranda cradles a glass of red wine and lays out the philosophy that shaped his time in office.

“I really believe that we are as rich as any country in the world, but our currency is our biodiversity,” he said. “The challenge is how to create value from biodiversity while keeping it alive.”

For Manrique Miranda, debt-for-nature swaps became a way to do just that. During his tenure from 2021 to 2023 under President Guillermo Lasso, he helped engineer Ecuador’s first modern swap: reducing $1.63 billion in debt held by Credit Suisse (now UBS) to $656 million, while establishing a large marine reserve near the Galápagos Islands and a $323 million conservation fund to protect it. He then set in motion the discussions that would evolve into Ecuador’s ambitious Amazon debt swap, known as the Amazonian Biocorridor Fund.

As Manrique Miranda was negotiating those deals with bondholders, nonprofits and other Ecuadorian ministries, President Lasso was making his own appeal abroad—flying to Beijing to plead for relief from Chinese banks. Years of heavy borrowing under his predecessor, much of it backed by Ecuadorian oil, had left the country locked into continued extraction and owing more than $5 billion to China.

Lasso returned claiming a modest victory: China agreed to push back repayment deadlines and trim interest rates. Such incremental renegotiations have become a hallmark of how Beijing manages its sweeping amount of distressed debtors, reflecting the Communist Party’s generally inward-facing priorities and commercial-driven approach to lending.

Those working to bring China around to debt swaps say the appeal for creditors is twofold: They can move troubled debt off their balance sheets while securing some ready cash now. Institutions like the Inter-American Development Bank and the U.S. International Development Finance Corp. have played a pivotal role by providing political-risk insurance and other credit enhancements that de-risk the transactions—making the deals financially viable in the first place.

For nation-state creditors, the benefits extend beyond balance sheets. The swaps provide a reputational boost that can translate into political leverage down the road, all while broadcasting the creditor government’s environmental bona fides on the world stage.

Back in Cuenca, an Andean gateway to the Amazon, Manrique Miranda said that even if Beijing won’t step in as a creditor, he believes it could contribute in ways similar to the United States’ support for the Galápagos and Amazon Biocorridor deals—providing critically important political-risk insurance.

Manrique Miranda has ideas in mind, pointing to an unprotected marine zone north of the Galápagos, mangrove forests along the mainland coast and gold reserves that could remain unmined if a future deal made conservation the better option.

“China,” he said, “could be a player.”

Others who share Manrique Miranda’s cautious optimism see another factor at work: Chinese President Xi Jinping has spent recent years casting his country as a global champion of biodiversity and the architect of a new “ecological civilization.”

An Ecological Contradiction

At a global biodiversity summit hosted by China in 2021, Xi appeared on a massive video screen to unveil a bold new idea: a world where humans and nature coexist in harmony. He invoked images of panda sanctuaries and sprawling national parks where elephants and tigers roam, framing conservation as both noble and achievable.

That vision is not just rhetoric. Under Xi’s rule, the concept of an “ecological civilization” has been written into China’s constitution alongside provisions cementing his own indefinite rule. On the international stage, Xi presents himself as an environmental visionary, repeating one of his favorite slogans: “Green mountains are gold and silver mountains”—in other words, protecting nature pays.

For many outside China—especially in the United States, where conservative lawmakers invoke China as a foil to justify America’s own pollution-heavy industries—the country still conjures images of smog-choked skylines and blackened rivers. But that picture is increasingly outdated.

After decades of severe industrial pollution, Beijing has imposed some of the world’s strictest environmental regulations. It has outspent every other nation on renewable energy, built a vast corpus of environmental scientists and created national parks and protected areas on a scale larger than Yosemite and Yellowstone combined.

Over the past 40 years, China has become one of the most re-forested parts of Earth after Chinese officials ordered the planting of millions of trees to combat flooding, deforestation and the encroachment of the Gobi Desert in the northern part of the country. This effort, known as the “Great Green Wall,” has made China one of the world’s leading technical experts in “greening” land that’s been degraded or overused.

But China’s environmental turnaround within its borders has led to a growing ecological footprint abroad as the country shifts its extraction to forests, mountains and seascapes in Belt and Road Initiative partner countries.

To longtime China scholar, Judith Shapiro, this transformation is both impressive and troubling.

“There’s been real progress—air quality has improved, pollution enforcement is far stronger, and ecological restoration is happening at a scale few other countries could pull off,” she said.

“But the approach is extremely technocratic and top-down. It doesn’t involve public participation, community oversight or grassroots decision-making,” she added.

That’s a consequence, Shapiro said, of the ruling Communist Party’s authoritarian governance and control over its citizens, which has only intensified under Xi.

The human cost has been stark. One of the clearest examples is China’s “Ecological Conservation Redlines,” a sweeping system that designates large swaths of land for protection and restricts industrial and residential use. While the policy has helped revive degraded ecosystems, it has also displaced millions from rural areas into cities, creating a new class of urban poor.

“It’s a form of quiet dispossession,” said Jesse Rodenbiker, who has conducted extensive field research in rural China. “People wake up one day and find they can no longer farm the land they’ve lived on for generations.”

Despite the social costs, the Communist Party hails ecological redlining as a triumph, an efficient way to conserve land by urbanizing rural populations and giving some people residency status. The model echoes the United States’ early conservation history, when Native Americans were forcibly removed to create national parks such as Yosemite. That “fortress conservation” philosophy was later exported overseas with more devastating human-rights consequences.

As the global conservation community increasingly reckons with these legacies, Beijing is positioning elements of its model as an export. Through the Kunming Biodiversity Fund announced at the 2021 summit, China has pledged more than $230 million to help developing countries meet their biodiversity goals. Coupled with a rapidly expanding web of technical exchanges, training programs and environmental assistance, China has cultivated what scholars describe as “green soft power”—a strategy that bolsters its influence in the Global South.

“China,” Rodenbiker said, “is offering resources others aren’t.”

A Black Box

On a sun-streaked cafe patio in Quito, Prieto leaned forward in a plastic chair, the environmental lawyer’s energy unflagging after a long day of meetings. Nearby, the capital’s late-afternoon traffic snaked around colonial edifices and plazas, fusing the tang of exhaust fumes with roasting coffee beans in the high Andean air.

Prieto was eager to talk. He has spent years grappling with the consequences of extractive foreign investment in Ecuador, projects promising beneficial development but leaving rivers slick with oil, forests razed and Indigenous communities displaced. His work has included a landmark case against Chevron, whose predecessor Texaco dumped millions of gallons of toxic waste into the Amazon.

“I understand well how Western companies operate,” Prieto said, referring to the mechanisms he’s used to try to hold those firms accountable. “China, though, is a black box for us.”

Today, Prieto is president of the Quito-based Center for Economic and Social Rights (CDES), a nonprofit critical of Ecuador’s debt swaps, alleging they lacked transparency and public participation. In 2024, Prieto and CDES won concessions from the Inter-American Development Bank, a guarantor of the Galápagos transaction, to improve public access to information about the deal’s conservation fund.

Prieto has broader concerns about the deals: “They don’t help sustainability or protect nature effectively,” he said, noting that their complexity and drawn-out structure tend to generate substantial income to lawyers and administrators. He also takes issue with how communities are treated.

“In the Galápagos and now in the Amazon, Indigenous communities are often sidelined,” he added. “Only a small, select group is consulted.”

More than a million Indigenous people call Ecuador home. Many live in the Amazon and do not identify with the umbrella organizations typically brought to the negotiating table. That mismatch has long dogged both extractive and conservation efforts in Ecuador, resulting in processes that often overlook the diverse realities and consent of the communities involved.

Prieto said the lack of transparency surrounding environmental decisions in Ecuador is troubling, noting that the state-owned Chinese mining company he is currently suing has refused to release its waste pit construction plans. It cited a confidentiality clause it negotiated with the Ecuadorian government. Earlier this year another Chinese mining firm’s waste pit collapsed in Zambia, causing catastrophic destruction. Advocates there have also struggled to obtain that company’s planning documents.

Prieto worries that the details of any potential debt-for-nature deal could be similarly obscured.

According to Prieto and news reports, communities near the Amazonian mine have faced displacement, environmental contamination and other abuses, including violence against Indigenous women. “Communities feel they have no recourse,” Prieto said.

Many of those communities, academics and advocates also have ethical objections to debt-for-nature deals, which they argue has led to the “financialization of conservation”—treating nature as an asset to be priced rather than as a living system with inherent value. (Ecuador’s constitution is the only one in the world to recognize that nature, like humans, has rights to exist).

Even as China considers debt swaps for renewables or development—investments that can offer Beijing a clear financial return—tying debt relief to conservation could be a nonstarter, said Junjie Zhang, an environmental economist with Duke Kunshan University. China’s priority, he said, has always been development, not aid.

Most Chinese officials, he added, believe struggling countries must first “make a living” before tackling anything else. Debt swaps for conservation strike them as risky, even counterproductive.

“If you swap debt for nature, what about in the future? Can the country generate enough revenue? Then you again ask for money,” Zhang said.

And China, with its fiercely competitive economic culture and domestic sensitivity to giving money away, is wary of assuming the role of global green financier.

“China doesn’t want to be a leader,” he said. “A leader needs to pay.”

Yunnan Chen, a research fellow with the London-based overseas development think tank ODI Global (formerly Overseas Development Institute), pointed out that China went into debt when it pursued its own industrialization.

“It doesn’t necessarily see debt as inherently a bad thing. It sees it as a necessary phase that developing countries have to go through to make the right kinds of productive investments in order to then generate growth. And that is also why I think it’s resistant to giving that kind of concession or debt relief.”

When China extends debt relief—zero-interest loans or loan write-offs—it’s subsidized by the country’s foreign aid budget. “It’s a tiny, tiny proportion of the portfolio and it’s usually only the ones that are at the end of their maturity,” Chen said. “And it’s kind of a tick-the-box exercise for the news headline.”

Kevin Koenig, who has tracked China’s footprint in Ecuador for more than a decade, is blunt about the prospect of Beijing stepping into the conservation arena.

“I don’t want to call it greenwashing,” he said. “But if there were a real interest in biodiversity protection or debt cancellation, you’d do that differently, not: ‘We’re going to continue extraction, and on the side we’ll do a debt-for-nature deal’ very far away from the places their investment projects are destroying.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Koenig sees the same contradictory elements in Ecuador’s existing debt-for-nature deals. They may channel money into protected areas, he said, but they don’t touch the forces driving deforestation and emissions in the first place. Even as the government celebrates the Amazonian Biocorridor debt-swap, it has continued to expand mining and approve new oil production blocks across the Amazon.

“These swaps won’t solve the fossil fuel or climate problem,” Koenig said. “They might save certain areas on paper, but they’re full of contradictions—countries promising a transition while doubling down on extraction.”

An Open Door

Since Ecuador pioneered one of the earliest debt-for-nature swaps in the late 1980s, the model for the deals has changed dramatically. After a period in which wealthy countries forgave portions of developing nations’ debt, the swaps have shifted into far more intricate, privately financed transactions. Today’s versions are vastly larger, often restructuring hundreds of millions or even more than a billion dollars in sovereign debt, and requiring layers of legal, financial and political coordination.

Ecuador’s Amazon swap, backed by The Nature Conservancy and public financial institutions, cut Ecuador’s debt obligation to some private bondholders from $1.53 billion to $730 million, while directing part of each payment into a conservation fund expected to raise $460 million over 17 years. The proceeds will go to Indigenous communities and conservation projects.

Speaking from a glassy high-rise in downtown Quito, Galo Medina, The Nature Conservancy’s Ecuador director, recalled just how arduous it was to pull off the deal. Initiated in 2022, the transaction outlasted two presidents and five environment ministers. Beyond the financial restructuring, the government codified new conservation commitments into law and, with The Nature Conservancy and other partners, established an independent trust fund to manage the money.

Medina insisted the trust fund is legally bound to fulfill conservation requirements set by the Ecuadorian government—not creditors who participated in the transaction or any other party. The fund also has to comply with Ecuadorian law, including the requirement that local communities are consulted about activities that could impact them.

The trust fund, he explained, is overseen by an independent board, including a representative from an Amazonian Indigenous organization. Once the fund is fully operational, he expects it to distribute roughly $17 million annually for conservation. The first call for proposals is expected toward the end of January.

“The main aspect that we’re looking for is the involvement and direct participation of local and Indigenous communities in the Amazon,” Medina said.

But he also acknowledged the tension at the heart of the effort—that the region the fund aims to protect is also where the government is expanding oil production and mining. His colleague, financial specialist Mónica Chávez, underscored the broader context: Developing countries would like to invest more heavily in conservation and climate commitments even as they face severe fiscal constraints.

“Then comes something like this, a debt-for-nature swap, and offers the chance for our country to send money for conservation that would be impossible in other circumstances,” she said. “This is an opportunity for Ecuador.”

As for whether Ecuador might one day participate in a swap with China, Chávez chose her words carefully.

“If it was an open door,” she said, “maybe we’d explore that.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,