Planet China: Eleventh in a series about how Beijing’s trillion-dollar development plan is reshaping the globe—and the natural world.

CHANCAY, Peru—The elevator doors leading to the fifth-floor control center open like stage curtains onto a theater-sized screen.

This “Operations Productivity Dashboard” instantaneously displays a battery of data: vehicle locations, shipping times, entry times, loading data, unloading data, efficiency statistics.

Most striking, though, are the bold lines arcing over the dashboard’s deep-blue Pacific—digital streaks illustrating the routes that lead thousands of miles across the ocean, from this unassuming city, to Asia’s biggest ports.

Chancay sits at a curve along the ocean, about 50 miles north of Lima. Until recently, it was best known for its medieval-themed amusement park, a crescent of beach and a row of seaside restaurants. Now it’s home to South America’s newest, most technologically advanced deepwater megaport and the epicenter of China’s bid to control the flow of goods to and from this commodity-rich continent.

For Peru, the recent opening of the port here was the realization, nearly two decades in the making, of a dream to position itself as South America’s global transportation hub, the continent’s primary launching point for a straight shot across the Pacific to Asia’s biggest economies.

For China, the port delivers a strategically direct route for the critical minerals and agricultural commodities coming off the continent, and in the other direction, a more expedient channel for its cars, machinery and electronics to stream into South American markets.

The port represents Peru’s first project under the banner of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing’s $1.3 trillion bid to remake how the world travels and trades, and collectively speaking, the most ambitious infrastructure project in history. It is China’s flagship infrastructure investment in South America—and a crucial node in Beijing’s global strategy for securing access to critical commodities.

It also brings China logistically closer to one of its chief goals: direct access to neighboring Brazil and the massive amounts of timber, soy and beef produced in the Amazon rainforest. Now, in theory, these commodities no longer have to travel through the politically fraught Panama Canal or around the continent’s southern tip. The new megaport, the only one in South America that can manage the largest class of fully loaded container ships, cuts the transport time by 10 days or more.

First, though, these commodities have to make their way to the port—and to do that, they have to somehow cross the Andes, the vertiginous mountain system that traces the western edge of the continent, from Venezuela to Chile.

There is no good, easy way to haul goods over the Andes now. That is changing.

The port has reawakened old ambitions of roads, railways and water routes that could connect the riches of the Amazon to the continent’s west coast and the world’s largest ocean. The prospect of a fast track across the Pacific has sparked new momentum—a willingness to reconsider the engineering challenge posed by the world’s longest mountain chain.

“The port is a magnet,” said Luis Fernandez, executive director of Wake Forest University’s Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation. “They’ll find more efficient ways to get over the Andes, to plug into Chancay.”

But environmental scientists and forestry experts warn that the economic pull of the port will speed the destruction of the Amazon, the planet’s most critical, climate-stabilizing terrestrial ecosystem.

The port and its faster link to massive Asian economies, they warn, will deepen and expand an extractive network of roads, railways and waterways that have already eaten into the rainforest, a web of arteries carrying oil, gold, timber, beef and soy to markets around the world.

The pressure could push the rainforest over the edge, transforming it from the world’s largest terrestrial carbon sink into a massive emitter of planet-warming gases. Some research suggests the forest is already at or near this potentially catastrophic tipping point.

“China wants everything in the Amazon,” said Julia Urrunaga, director of Peru programs for the Environmental Investigation Agency, an international nonprofit that investigates environmental crimes. “And in one way or another, all these routes are connected to the port.”

In July, seven months after the port’s inauguration, China and Brazil formally announced they would explore the possibility of a railway leading from Brazil’s Atlantic coast directly to Chancay. China has already committed $50 billion toward infrastructure in the region.

The massive undertaking would ultimately create a beeline for commodities to flow more directly from Brazil to China, already its biggest trading partner, and augment a notoriously troubled and underutilized highway, completed in 2011, that runs from Brazil’s western Amazon to the Peruvian coast.

Even if the newly proposed cross-continental railway is never built—and some analysts think it won’t be—the lure of China’s appetites and wealth will stress the Amazon ecosystem, simply because the port will spark investments in other road, rail or waterway projects to serve it, whether China is directly involved or not.

“When you start talking about these big corridors, it creates incentive for a lot of small routes,” said David Salisbury, an associate professor of geography at the University of Richmond who has extensively studied the impact of infrastructure on deforestation in the Amazon. “In a world where carbon storage is absolutely necessary for sustaining a stable planet, increasing the axes of forest degradation—whether it’s a road or a railway—is a big mistake.”

A port is just a port until there are roads and railways leading to it, and China has made clear that access to its biggest South American infrastructure project is a priority. Although China is clearly the world’s clean energy leader, there’s little, if any, research into the climate impact of its infrastructure investments, including any kind of holistic analysis of the port and its potential impact on the Amazon or neighboring and equally vulnerable ecosystems, including Brazil’s Pantanal and Cerrado. Most of China’s infrastructure investments, meanwhile, are in the world’s equatorial midriff—in nations that are rich in resources and climatically critical, but with weak, often corrupt governments and few environmental safeguards.

When China wants to build something, countries—including Peru—are quick to ease or overlook environmental standards and requirements for public participation, critics say, even if that means destroying natural resources or communities.

“Unquestionably any infrastructure, and any attempts at development, will put a lot of pressure on the Amazon,” said Enrique Ortiz, a Peruvian tropical ecologist who runs the Washington, D.C.-based Andes Amazon Fund. “Are there safeguards? That’s where we’re so weak.”

In Chancay, residents say, the developers of the port tore their city apart. In their zeal to embrace its economic promise, city leaders ignored local complaints, residents told Inside Climate News. The project proceeded without the legally required public input and access to information, advocacy groups found, ruining lives and homes in the process.

Hundreds of miles to the west of Chancay, in a rainforest so lush and filled with species that scientists haven’t yet catalogued them all, new worries are percolating. Chinese investment is increasingly prominent, with Chinese machinery, trucks and workers seemingly everywhere.

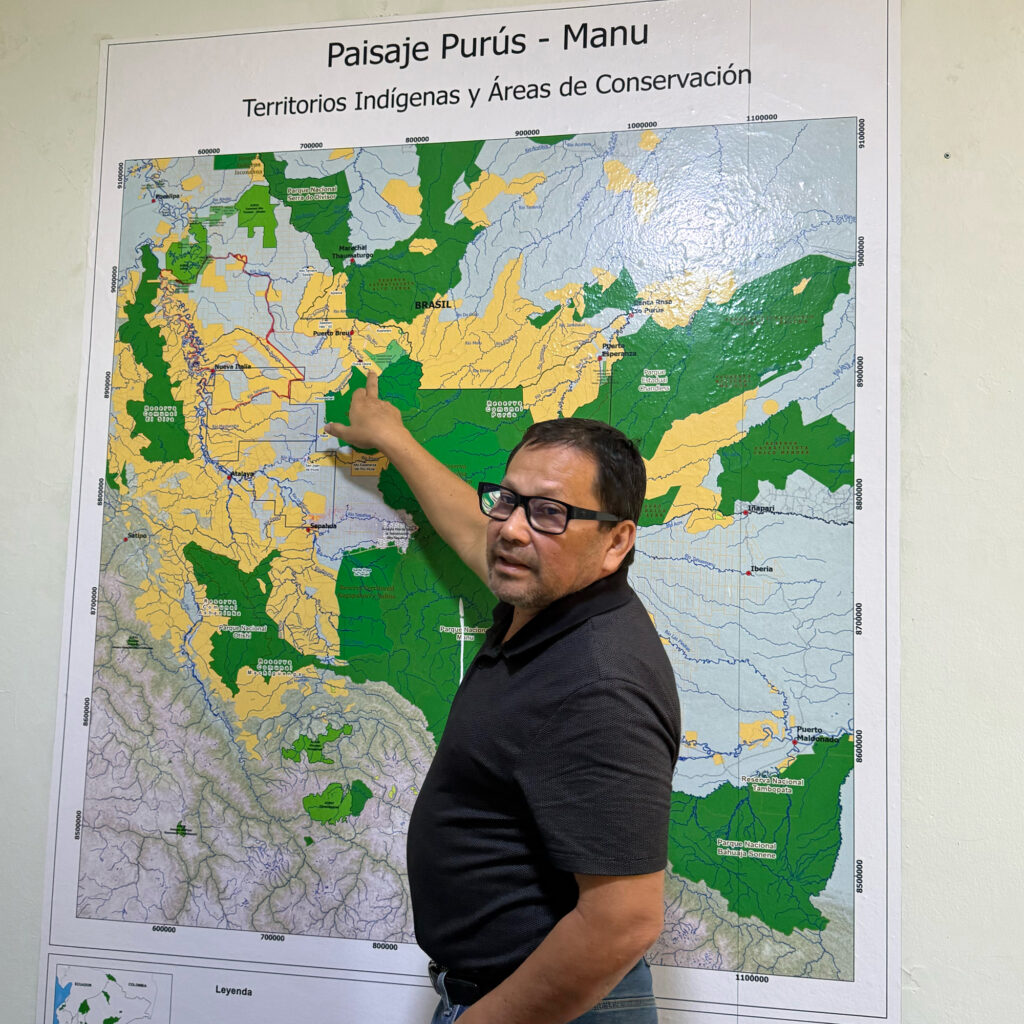

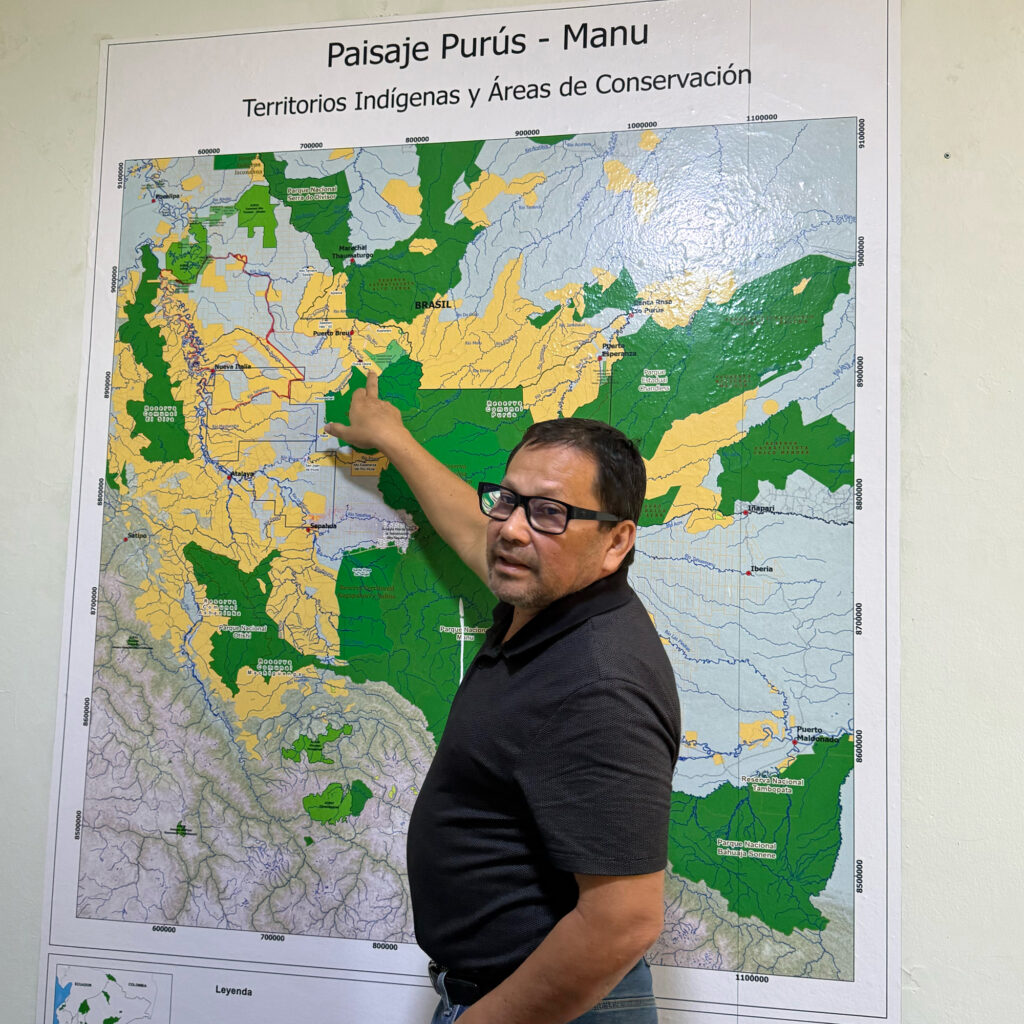

Chris Fagan runs the Peru- and U.S.-based Upper Amazon Conservancy. His main objective right now is to stop a roadway from running through a pristine section of the Amazon, which would decimate Indigenous cultures and the rainforest itself.

“The influence of Chinese money on the Amazon can’t be overstated,” he said.

Roads and a Revolution

When the Chinese shipping conglomerate COSCO signed the deal to buy a 60 percent stake in the Chancay port, most people guessed what would come next.

“They need the roads,” Urrunaga said. “We knew that from the beginning—that this would come with a road.”

What no one yet knows for sure is where exactly the new roads—or railways or waterways—might be. The port will likely beget many.

The Brazilian government last year announced its plans to build five major new routes through the Amazon to connect with Pacific ports, including Chancay. The roads are part of a larger project that includes modernizing or building 65 highways, 40 waterways, 35 airports, 21 ports and nine railways.

From the Brazilian town of Cruzeiro do Sul, in the western Amazon, a long-discussed 430-mile roadway could finally be paved westward to the city of Pucallpa, the heart of Peru’s timber industry. From there, a road already leads to Chancay.

The new road would cross the region where the Amazon begins—the famously disputed source of the massive arterial sprawl of coffee-colored waterways that form the Amazon basin and its namesake river. This region, which straddles parts of the Andes and the Amazon rainforest, also contains two national parks that are home to 10 Indigenous tribes, including some living in voluntary isolation.

“It’s this huge, intact roadless area and one of the most biodiverse landscapes in the world,” said Fagan, of the Upper Amazon Conservancy, which is headquartered in Pucallpa. “It’s a really important place for global conservation and climate goals.”

It is, according to Fagan, among the biggest, wildest places left in the world. And the road could transform it irrevocably, with its effects spreading far beyond the region itself. If the road is built—as local politicians are pushing for now—it will connect to a handful more major roadways that cut across the wider Amazon, and to yet more that are still in the planning stages.

Since the Brazilian military cut roadways into the Amazon to facilitate its exploitation in the 1960s, a growing body of research has tracked the effects of infrastructure on the rainforest. Deforestation here occurs in a “fishbone” pattern where a primary road leads to secondary roads spiking off it, fragmenting and weakening the forest. This pattern, clearly visible from satellite images, crosshatches across much of the region. Researchers say it’s even more destructive than clearcutting big swaths of forest.

Adding to the pile of research, a study earlier this year found that every one kilometer (or roughly half-mile) stretch of primary road cut into the rainforest led to 50 kilometers (31 miles) of secondary road—and that the secondary roads triggered more than 300 times more forest degradation or loss.

“The area is experiencing this incredibly rapid expansion of secondary, or unofficial, roads,” the University of Richmond’s Salisbury said, referring to the region where the Pucallpa road would be completed.

Read More

A Massive, Chinese-Backed Port in Peru Could Push the Amazon Rainforest Over the Edge

By Georgina Gustin

This May, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva met with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing to discuss the new railway that would cut more than 3,000 miles across the continent, from the Atlantic port at Ilheus to Chancay.

“This represents a revolution,” Simone Tebet, Brazil’s minister of planning and budget, said at the time. “The plan is, in fact, to rip Brazil from east to west.”

In July, Brazil and China formally announced a five-year technical study to determine what route the railway would take—a sign that the countries are serious about making the project happen.

One of the possible routes, researchers say, is along the same stretch from Cruzeiro do Sul to Pucallpa where the road is again under discussion.

“If it comes through Pucallpa that’s going to be a huge disaster, ecologically and socially,” Salisbury said, noting the especially pristine nature of the area.

Another possible route is along an already problematic road, known as the Interoceanic Highway, that leads from the western Brazilian Amazon, over the Andes, to Lima. Road and railway ecologists say that while rail is seen as less damaging to forests, its potential impacts are underestimated.

“Are railways better than roads?” said Elizabeth Losos, an adjunct professor at Duke University who runs the ISLe Initiative, a network of educational efforts to make infrastructure more sustainable. “They take up the same amount of space, but for the most part, people get off at stations and can’t get off at multiple places in between. But when they build the railways they create service roads that serve them.”

Salisbury has considered the same question. “Railways are a lot less environmentally and culturally impactful than roads—and that’s crucial,” he said. “But how are you able to control that they remain purely railways? Once you make a linear clearing through the rainforest—how can you stop people from expanding beyond that?”

Automatic, Electric and Huge

Jason Guillén Flores is the Chancay port’s safety and environment manager, an engaging evangelist for the state-of-the-art technology that will bring the continent’s raw materials to China and Chinese goods containing those raw materials, transformed, back to the continent.

One day this July, dozens of Chinese-made electric cars had just disembarked from a massive roll-on/roll-off ship and were awaiting distribution into the expanding Latin American market.

From the moment the ships arrive in the docks, their payloads are controlled from the fifth-floor command center. From a giant observation deck, visitors can watch as a fleet of 500 driverless electric trucks shuttle goods from the docks to waiting vehicles.

“All this port is electric—all the different equipment and trucks. All electric,” Guillén Flores said. “This is the fifth port in the world to be all automatic. The other four are in China.”

Guillén Flores walked from the Area de Centro de Control to the Area de Control Remoto where half a dozen women sat at desks, remotely maneuvering the massive cranes that hover in the wintry gray at the docks’ edges. Operating a crane from within its cockpit is exhausting work, Guillén Flores explained, leaning over to demonstrate the hunched position operators often sit in.

“Here there is air conditioning and coffee,” he said. “Six people control 50 cranes.”

Beyond the command center, the loading platforms and the docks, a 1.7-mile breakwater curves through the ocean, creating a protected area for ships to enter the port. It stands nearly 30 feet meters high—enough to withstand a tsunami caused by a 10-degree quake. “No problem,” Guillén Flores said.

Constructing the port, he said, required dredging the approach to a depth of nearly 60 feet, moving 7.6 million cubic yards of dirt and rocks and digging a more than mile-long tunnel under the city. Altogether it took 438 explosive blasts.

Guillén Flores stressed that the goal of the port, at least initially, was to help turn Peru into an agricultural powerhouse, ready to supply hungry Asian markets with produce.

“It’s a general vision for Peru to improve ports and agriculture so we can position ourselves as a top country in exporting agricultural products,” he said. Now, he added, a refrigerated container full of Peruvian blueberries or asparagus can reach Shanghai in a mere 23 days.

But the port is designed to handle more than fruits and vegetables.

In 2007 a Peruvian ex-Navy admiral named Juan Ribaudo de la Torre launched an ambitious plan for turning this modest bump of oceanside land into a major port. With his deep connections in the military and government, he eventually found a strategic and willing partner—the Peruvian mining giant Volcan, the world’s fourth largest silver producer and Peru’s largest producer of zinc.

Already some local fishermen were concerned about the fate of their fishing grounds and Volcan’s long track record of environmental violations. In 2011, through a subsidiary, Volcan acquired 50 percent of the port project, from the company launched by Ribaudo, for $450 million. Around the same time, lawyers with connections to Volcan formed an offshore company, based in the British Virgin Islands, to secretly begin purchasing plots of land for the port.

When Ribaudo died in 2013, Volcan took full control of the project under the name Terminales Portuarios Chancay. That same year, Peruvian regulators approved an environmental impact study for the project, but residents in Chancay were not given adequate opportunities to access hearings or participate in the review process, advocates say.

“The study was approved in an irregular manner because the civil population didn’t take part as required,” said Alejandro Chirinos, a researcher with the Lima-based environmental and social justice group CooperAcción. “And why were the people not considered? Because people didn’t want Volcan.”

In 2019 officials from Volcan and the Peruvian government attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. By the end of the event, China’s COSCO Shipping Ports Ltd. had signed a deal to buy 60 percent of Terminales Portuarios Chancay.

As the scope of the project expanded with Chinese involvement, so did the price tag. New estimates put the cost of the project at $3.6 billion over three phases. Now, with the financial commitment, the pressure was on regulators to smooth over any potential bumps in the approval process and make sure opponents in the community didn’t stand in the way—though they tried.

Even though it’s a privately operated port, Peruvian government entities—the national police, immigration, health and various inspection services—are already in place here, to expedite inspections and speed shipping. Their presence suggests how deeply integrated the Peruvian government and China have become.

Eventually, the Chancay port could be encompassed by a special economic zone, giving tax breaks to companies with operations there. “Apple, GE, Samsung will move to Peru and establish hubs here for all of South America,” Guillén Flores said, explaining the broader plan.

But many people who live here believe too much has been given away already.

A City Torn Apart

Miriam Arce said the explosions just began one day in 2016, without any warning or explanation.

Then, quickly, the construction of the massive deepwater megaport disfigured her city. Over the course of the next two years explosions shook Chancay and its 60,000 residents several times a day. Entire hills and bluffs at the ocean’s edge were blasted away to accommodate the port’s facilities. Walls in peoples’ homes cracked. Foundations crumbled. Houses collapsed when workers blasted an access road that leads to a tunnel under the city. Some species of birds left the city’s oceanside wetlands and never came back.

“They were exploding the hills, the tunnels, at the port—all at the same time,” Arce said. “Can you imagine? It was crazy.”

Arce, an artist who runs a small general store out of her house, organized a community group—Frente de Defensa de Chancay (Chancay Defense Front)—in 2014, after learning about the plans for the port. She was particularly concerned about an environmental impact statement that advocates say the government approved in 2013 without releasing a summary to the public or getting adequate public input, as the law requires.

“I started to investigate the consequences—how it will impact people and the environment,” she said. “We discovered many irregularities with the authorizations and the lack of transparency.”

Petite and bespectacled, with a penchant for yellow Snoopy-festooned sneakers, Arce has become a feisty agitator, a persistent burr in the sides of local politicians.

She petitioned for access to public meetings. She pushed for documents. Amid the groundswell of protest Arce and others were stirring up, she became a target. She said she got death threats on the phone. Arce and other Chancay residents say that the then-builders of the port hired a subcontractor to harass and threaten them so the threats couldn’t be traced back to the developers. After she was roughed up during a protest and her phone was taken, Arce filed a complaint with police.

As Arce dug into the situation, she learned that she may have been clueless about the port owner’s plans before 2014, but not everyone was. Terminales Portuarios Chancay, anticipating concerns from local fishermen—a powerful, well-organized cohort in Chancay and Peru more broadly—had already contacted fishing unions, according to Chancay residents. They offered the members scholarships for their children’s education. Many took it.

“They paid to divide us,” Arce said. “We lived in peace for so many years, since we were children. But this project broke things.”

Standing outside the blue concrete box that houses the Association Sindicato de Pescadores Artesanales del Puerto de Chancay, one of several associations that represent fishermen here, Julio Perez said that fish populations near and off the coast of Chancay have plummeted because of the port’s construction and the ongoing flow of ship traffic. But he said he and most other members of the 300-plus member association have made peace with that.

Many of them got 12,000 Peruvian soles (about $3,400), earmarked to pay for tuition, he said. The developers also pay for the occasional party at the association’s headquarters.

“We’re happy,” he said, scanning the street in front of him.

Not everyone is, however.

In a square in the city of Huaral, north of Chancay, fisherman Antonio Luis sat on a curb, wearing the uniform of most local fishermen—a matching track suit and running shoes. He came equipped with data showing the decline in fish populations and the marine species on which those populations depend.

Luis, president of another association called the Artisanal Fishermen of the Small North, said whatever payments the developers offered were not worth the declines.

“Before 2018, we put the net in and we fished enough in order to not fish for two or three days. Enough to live comfortably,” he said, adding that a typical day’s catch was 200 kilograms or more. “Nowadays you go to the beach and it’s nothing like that. I put in a net and if I’m lucky, I can get 15 to 20 kilograms a day. I catch enough to eat. Not enough to sell, which is what I need.”

The “luxury fish,” like corvina and sole that are prized for ceviche, the national culinary mainstay, are especially rare these days.

Luis said that the developers only consulted with a handful of the many fishing associations along this stretch of coast—not his or several others. He sees the payments offered to the other groups as bribes to shut up.

“I’m not opposed to investment,” Luis added. “I’ve just asked for development … between the city and the government without stepping all over the environment.”

Today, with the first phase of the port in full operation, this upended city seems to be in suspension as residents wait for the next wave of construction.

On a quiet July weekday, in the southern hemisphere’s winter, restaurant workers waved menus at passersby, trying to lure them into mostly empty seats. At the beach, dozens of colorfully painted wooden fishing boats were lodged on the sand. No one was out on the water. The fishermen milled around, staring out at an ocean that used to provide an abundant livelihood.

“Mining companies pay people for invading their land. We’d like to get paid for our ocean,” said one fisherman, who would only give his first name, Elias. “The Chinese are just like the U.S. They’re the big power. If they invest here, if they shared their profits, we’d be happy.”

Near the end of the beach, a handful of tourists climbed little footpaths that lead up a giant bluff to get a view of the sprawling port complex hidden on the other side.

Some fishermen have started a side hustle: Charging a few soles to guide visitors to the top.

On the November day last year when the port was lavishly inaugurated, Arce was not in attendance. Nor was Luis. In fact, Arce said, few of Chancay’s ordinary citizens were there because the celebration was cordoned off. Busloads of police were brought into town to enforce the perimeter of the port, which by then had been encircled with a tall fence.

The message was clear: The city’s new port did not belong to the city.

The Perfect Place

Wendy Ancieta, a lawyer with the Peruvian Society for Environmental Law, has deep expertise with the country’s environmental impact review process—and its loopholes. She remembers interviewing a gas station owner who was required to get an environmental review for his business. When she asked him who oversaw the review process, he admitted it was a cook at a nearby restaurant.

The country has an abundance of environmental laws, but they’re rarely enforced, according to Ancieta. If a company wants to sail through the environmental review process in pursuit of a massive project—with as little pushback as possible—Peru is a good choice.

China, she said, “came to the perfect place.”

The port’s developer—now called Cosco Shipping Ports Chancay Perú (CSPCP), 60 percent owned by COSCO and 40 percent by Volcan—hired a contractor to conduct the required environmental analysis. In theory, such a document gets thoroughly picked apart by SENACE, the government agency responsible for reviewing the environmental impacts of big projects.

But in practice that rarely happens.

The Peruvian government allows developers of major construction projects to pick from a registered list of consulting companies that they can hire to conduct an environmental assessment. When the developer gets an assessment they don’t like—that might stand in the way of a project’s completion—they can withhold payment.

When the port’s developers were required by law to do a secondary environmental review, advocacy groups, including Arce’s, hired a researcher named Stefan Austermühle to analyze it for flaws and omissions.

Of the review process, Austermühle said, “You tell them: You will make a nice document for me, where there’s no impact, so I get this project approved. And if you don’t do that, I don’t pay you.”

Austermühle identified 50 problems with the environmental review’s findings. The groups then asked SENACE not to approve the project until these problems were corrected. Ultimately, fewer than half of them were addressed by COSCO—inadequately, according to the groups. The agency approved the project in 2020, two days before Christmas, when few people were looking.

In July of this year, the Peruvian media reported that six SENACE employees were charged with environmental crimes for approving parts of the project without COSCO addressing them first.

In a written response, SENACE said the agency held at least eight meetings and workshops with the public and with local fishing associations in 2019 and 2020, during the development and evaluation of the secondary environmental assessment. The agency recorded at least 1,800 individual attendances across the meetings. The agency also said it forwarded the problems that Austermühle identified in his analysis to the “project owner,” in accordance with federal laws.

In a written response, CSPCP said it had complied with all laws and that the approvals process “went well beyond regulatory requirements regarding public participation, both in the number and diversity of mechanisms implemented.”

The company said it categorically rejects “as completely false” the allegations that it hired a subcontractor to harass opponents of the port project. “At no time has the company hired or instructed subcontractors to harass, intimidate, or interfere with citizens’ participation during protests or demonstrations related to the Project. On the contrary, CSPCP maintains a permanent policy of respect for the right to free expression, peaceful coexistence, and open dialogue with all social stakeholders in the district of Chancay.”

Volcan and the Chinese embassy in Peru did not respond to requests for comment from Inside Climate News. The Peruvian Ministry of Transportation and Communications, which approved the first environmental assessment, before COSCO’s involvement in the port project, also did not respond to questions from Inside Climate News.

Juan Luis Dammert is a Lima-based researcher who studies government corruption and the evolution of infrastructure projects, including the Interoceanic Highway. Like most Peruvians, he is a keen observer of the country’s political ups and downs.

“There’s always corruption here, but we’re at a low point in Peruvian politics,” he said. “It’s corruption’s happy hour.”

The country has had seven presidents in the last decade, including two who are currently in jail for taking bribes from the Brazilian construction company that built the highway. In 2018, the country’s judiciary system was rocked by a corruption scandal. Former President Dina Boluarte, who presided over the port’s inauguration, was highly unpopular and accused of deadly anti-democratic crackdowns against protesters. She was impeached by the Peruvian Congress in October. Two other former Peruvian presidents were jailed on conspiracy and corruption charges in late November.

“We have, as a country, built a number of systems and structures for environmental protection, but now it basically doesn’t exist,” Dammert said. “Congress and the government—if they decide to do anything, they go ahead. They change the law. That’s the context in which this is happening: Now let’s build roads and railways through the Amazon!”

Chinese companies, Dammert said, aren’t necessarily worse or better than any others in their adherence to environmental laws. China’s position on environmental laws in other countries is, largely, not to meddle with them, in alignment with its “non-interference” policy. And, indeed, Chinese-backed companies have stopped a handful of projects, including a dredging project in Peru, over potential violations of environmental laws.

It just happens that Chinese companies are operating in parts of the world where those laws are weak. “There’s no difference between China and other countries in their concern for the environment,” Dammert said. “It very much depends on the host country. In this case, Peru.”

Or Brazil, where environmental safeguards are also collapsing.

The government is currently challenging the legality of a nearly 20-year-old pact, known as the Soy Moratorium, in which grain traders agreed to not buy soybeans grown on land deforested after 2008. The moratorium has been credited with slowing rates of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

In July, the Brazilian Congress approved a new bill that would ease licensing requirements for infrastructure projects deemed to be national priorities. Environmental groups called it the “devastation bill” and said the damage to the rainforest and to broader climate goals would be irreversible.

“It would make it easier getting infrastructure, like railways, approved without requiring environmental studies,” said Symington, of the World Wildlife Fund. “That’s unfortunate.”

Symington noted that Peru passed a similar law in 2024 that environmental groups say will weaken forest protections. The lowering of environmental standards comes amid a broader autocratic shift in Peru.

A recently passed law will prohibit advocacy groups from pursuing legal action against the government, including for human rights or environmental violations. The law has been widely condemned by international free speech advocates, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

“This makes it easy for China to operate as they want without any civil society groups complaining,” the Environmental Investigation Agency’s Urrunaga said. “It’s really crazy. … Not even China has a law like that.”

The erosion of democratic functions will usher in projects linked to the port that destroy parts of the rainforest without even the most rudimentary environmental review, environmental groups worry.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Leolino Dourado, a Lima-based researcher at the Center for China and Asia-Pacific Studies at Peru’s University of the Pacific says that shipping commodities through the Amazon and over the Andes to the Pacific makes no economic sense. It’s still cheaper, he said, to ship commodities out of Brazil.

“If you run the numbers, it’s more cost effective to export through the Atlantic, which is the traditional route,” he said. The Interoceanic Highway is a case in point, he added: “It’s really underutilized because it makes no sense economically.”

But infrastructure projects make perfect political sense. Roads, railways and waterways deliver infusions of cash for hard-up cities and regions, making these passages through the forest powerful forces, however destructive.

“Roads are a good way to get elected,” said Salisbury, with the University of Richmond. “It’s a good way to get politicians in Peru excited about China, even though it doesn’t make economic sense. And it allows the Chinese to have more impact on the Amazon—and Brazil and Peru—just by creating a corridor with a new form of transport, even if it’s not a gamechanger economically.”

Chirinos of CooperAcción authored a study that found a common thread in China’s Belt and Road projects: The countries that join in are a lot like Peru, with a high level of raw materials or other natural resources, but weak institutions and lax oversight. He and other researchers say that puts Peru at an economic disadvantage.

“The project will only take the raw materials and won’t allow us to develop,” Chirinos said.

César Gamboa is the executive director of the Peruvian organization Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Law, Environment and Natural Resources) and has written recently about his concerns that the country’s current political and economic environment will keep ordinary people from sharing in any financial gains from the transition to cleaner energies.

“Always, all the time, Peru underestimates the environmental and social impacts and overestimates the benefits,” Gamboa said. “This is the problem of the Chancay port. Everybody says this is a tool to get out of the political and economic crises, but it’s not. We are not prepared to identify the opportunities and we don’t see the challenges.”

Stepping Into a Vacuum

China and Peru have had ties going back nearly two centuries, when Chinese immigrants first came here. A very obvious legacy of this is chifa, a Chinese-Peruvian fusion cuisine that can be found in every corner of the country. But in recent years, China’s investments in Peru have soared. Ninety percent of the overall investment—about $28 billion in 2023—is linked to large, state-owned enterprises, according to a recent analysis from the University of the Pacific’s Center for China and Asia-Pacific Studies.

The port is the single biggest flag China has planted on a continent that the United States has long seen as its domain.

“China’s in our red zone,” said Laura Richardson, the now retired U.S. Army general who served as the commander of U.S. Southern Command from 2021 to 2024.

As Chinese-backed investments expand, projecting Beijing’s power in the region, allegiances and sentiment across South America are shifting.

The Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs and harsh immigration policies that disproportionately impact Latin American countries are increasing anti-American bitterness across much of the region, making China seem like a friendlier, more stable alternative, economically and politically.

The administration’s dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) earlier this year has only amplified resentments. After Colombia, Peru was the continent’s second-largest recipient of USAID funding, much of it directed at curbing coca plantations. USAID funding to Brazil was largely aimed at programs to conserve the Amazon.

China is stepping into the diplomatic and economic vacuum. Trade between the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States’ members and China rose from $450 billion in 2023 to $515 billion in 2024. Earlier this year Xi announced $9 billion in credit to the region and visa-free entry to China for residents of some countries. And while Chinese direct investment in Latin America for big infrastructure projects has slowed, it remains strong for certain industries.

“Nobody else is offering money for these projects,” Richardson said. “China comes along offering billions—$3.6 billion, with four-and-a-half billion annual revenue profit for this—how can you turn that down? Nobody else is offering anything like that.”

But at the same time, China’s environmental track record, both in the construction of its big infrastructure projects and in the supply chains of its imports, is drawing more criticism from environmental groups, researchers and residents.

China is the largest importer of commodities linked to deforestation, including soy, beef and timber, and the second-largest importer of palm oil, which together are responsible for about 40 percent of global deforestation rates. This, critics say, means China has a huge potential exposure to illegal deforestation.

In 2021 China signed on to a global pact to reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2035, acknowledging the role of forests in stabilizing the atmosphere. But recent analyses suggest the country may not follow through. The authors of a 2024 study wrote, “China’s foreign policy stance of non-interference and concerns about its food security are key obstacles.”

The European Union Deforestation Regulation is the most ambitious effort to date to stop commodities that cause deforestation from being imported into European markets. China, one of the biggest exporters of timber products to the EU, recently refused to sign on, citing security concerns related to sharing geolocation data. In November, at the annual United Nations climate conference, held this year for the first time in the Amazon, countries agreed to a $5.5 billion rainforest conservation fund. China said it supports the fund but would not be pledging money to it.

Studies have demonstrated that Chinese imports of illegal timber have climbed along with its involvement in tropical forested regions, including Brazil and Peru.

One study, from the Environmental Investigation Agency in 2018, found that only one-third of tropical timber shipments from Peru to China were properly inspected, and of those that were inspected, 70 percent were found to be from illegally deforested land.

Another study published in May found that Chinese imports of products known to cause deforestation between 2013 and 2022 were linked to the loss of roughly 4 million hectares of tropical forest, nearly 70 percent of which was illegally deforested. The greenhouse gas emissions from these imports were roughly on par with the annual fossil fuel emissions of Spain.

“While China is a global leader in domestic reforestation and renewable energy, this report highlights a critical blind spot of the environmental cost of its imported agricultural and timber commodities,” said Kerstin Canby, a senior director with Forest Trends, in a press statement published along with the report.

In an interview, Canby noted that China has implemented robust reforestation programs within its borders, but that has had a direct impact on vulnerable forests elsewhere, including the Amazon.

“China has been a star, but that has ripple effects,” Canby said. “Everyone’s trying to protect their own forest, but all that does is push demand to those countries that have the least amount of governance, the ones that are not putting in place protections for their own forest.”

Coda

From the rooftop studio where Arce paints landscapes of her coastline view, she can almost touch the netted scaffolding erected outside the walls of her house to keep construction dust and debris from flying into the windows. (It did anyway.)

Every day now, trucks come rumbling, idling at the entrance to the port, which is about 100 feet from her back door. She doesn’t know exactly what’s in them, nor has she or anyone else calculated the damage caused by their payloads. She just knows that soon there will be more of them.

Arce, and many of her neighbors, worry the city’s troubles may get worse as the port expands into its second and third phases of construction over the next several years, and as more roads and railways are built to serve it.

“There is no space for the people who live here. We would have to leave. Who are they going to take out of their houses?” she said. “That’s the next fight.”

She worries that cracks will continue to creep across the walls in the house she’s lived in since she was a baby or that the foundation could crumble one day. Then someone joked that she should ask the Chinese for compensation. Maybe one of the newly delivered electric cars.

Arce cracked a wry smile and looked out at the ocean, which that night was flat and still. “Or a new house,” she said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,